Ely Center of Contemporary Art | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | COVID-19

| Azin Moradi (Iran), Real Superheroes. Image Courtesy of the Ely Center of Contemporary Art. |

The figures lean in, their foreheads pressed together in a mess of blue-black hair. Sweat, rendered in strokes of creamy white, pools at the temples. On the left, a man raises his hands to his partner’s ears. Their mouths are hidden by design: a viewer can almost feel the breath sitting there, wet and warm, behind two identical respirator masks.

Azin Moradi’s Real Superheroes is one of almost 50 works in What Now? a new, ongoing virtual exhibition from the Ely Center of Contemporary Art. As an increasing number of museums bring their collections and curatorial practice online, the Ely Center has rolled out its digital presence with several online shows, studio tours, a virtual happy hour, and weekly Sunday critiques.

“Amid the current health crisis, we are all left looking not only at our present, but ahead to our future — what do we do now?” reads a call for submissions. “How is the current health crisis affecting you, and what does the future look like? Novels such as Brave New World, Handmaid's Tale, Fahrenheit 451 and 1984 describe surreal and dystopian futures that now seem eerily all too real—so what is the new normal? What Now?”

The exhibition is the brainchild of Gallery Coordinator and Curatorial Assistant Maxim Schmidt, an artist and Albertus Magnus grad who is currently based in Meriden. When state-mandated shutdowns began in March of this year, Schmidt and Gallery Director Debbie Hesse began thinking about how to take the center’s presence—usually based out of its Trumbull Street home—into digital space.

“The real essence of that is we want to offer social space,” he said, noting that the center has added so many interactive activities because it already has a built-in community. “Everybody needs a way to gather.”

| Jackie Brown (London, UK), Waking Up Earth. Image Courtesy of the Ely Center of Contemporary Art. |

That mission is twofold, Schmidt said. People still want to see and make art during a global pandemic, perhaps even more so because many of them are now working from home. The Ely Center also wants to remain relevant. Due to closures—it closed its Trumbull Street doors March 13 and does not know when they will reopen—the space is projecting a loss of at least $38,000. While Hesse is in the midst of applying for federal relief, she said that it remains important to her and to the center to continue paying part-time staff.

So in the midst of a global pandemic, Schmidt curated at least one exhibition with a global submission process. While the site’s other group show Your Pet Here provides a welcome distraction from COVID-19, What Now? looks it literally in the eye. With one click, a viewer is suddenly looking at different interpretations of the virus, from different corners of the globe.

“The way that everyone is interpreting this is so interesting,” Schmidt said in a recent phone call. “The diversity of what we've been getting in content, the global outreach that we've been able to do, the humanness in this art. It provides such interesting insight.”

The pieces, which come from 20 different towns and cities across the globe, speak to a COVID-19 experience that is at once shared and not shared at all, in a pandemic where some artists have lost their livelihoods and their health, and others are facing COVID-19 as a terrifying concept, but a concept nonetheless.

Pieces jump from humor and bite—Tali Margolin’s Readymade is a roll of toilet paper suspended beneath duct tape, à la Duchamp in the time of coronavirus—to calls for truth-telling and visual activism.

.jpeg?width=300&name=image-asset%20(1).jpeg)

In Amira Brown’s Rose Soul Cocktail (pictured at left), a bejeweled hand wraps itself slowly around a martini, depositing a dollar bill on the counter beside it. Inside, there’s a prickly, bulbous red shape that the viewer has come to recognize instantly: the coronavirus itself, right where a fat black olive should be.

There’s no way to see the barkeep on the other side of the equation, but they’re easy enough to imagine: a worker forced to slog through the last weekend before the state shut down, or maybe a business owner who is still offering take out because limited federal relief won’t be enough.

Or, in Brown’s take, maybe it’s an artist expected to make work for free. Everything is soaked in a pleasant, dark blush, which conjures both rose-colored glasses—worn only by those who can see a silver lining in a pandemic—and the red that comes next, a signal to stop and reassess everything.

“While I've been creating the wealthy elite who are couched in their mansions live off of our souls, bodies and lives,” she writes in an accompanying text. “Rose Soul Cocktail is a small piece addressing this reality.”

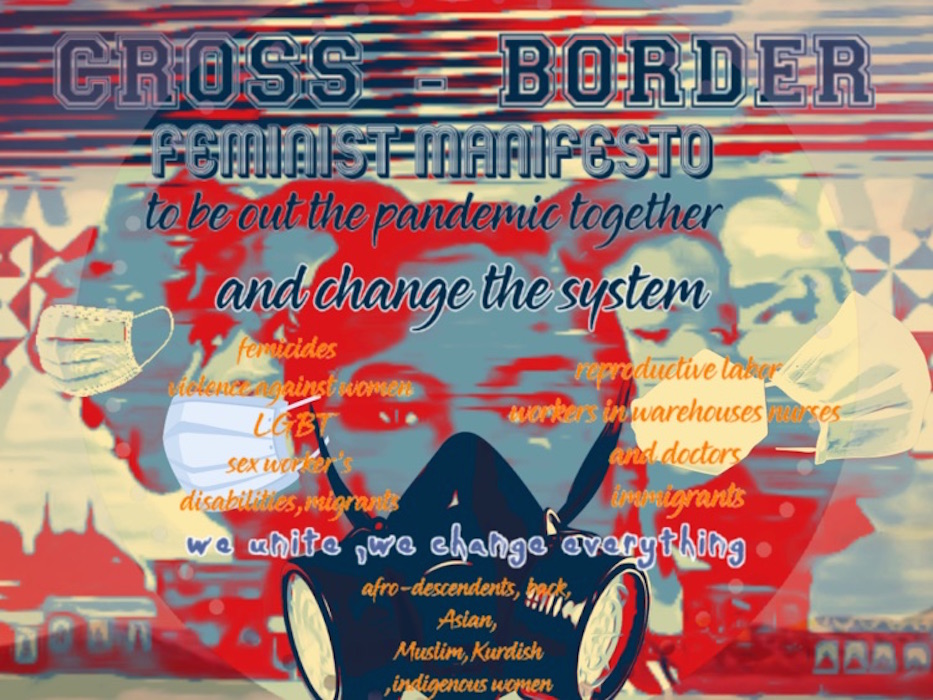

| Sarahi Zacatelco’s Cross Border Feminist Manifesto. Image Courtesy of the Ely Center of Contemporary Art. |

So too in Sarahi Zacatelco’s Cross Border Feminist Manifesto, a sort of artistic call-to-arms that puts COVID-19, intersectional feminism, and public health hand-in-hand. The piece, which feels like it should be displayed on a car during a physically distanced honk-a-thon, catches one with its mix of red, white and blue—not of an American flag, but the masked faces of at least five workers who build the background of the piece.

Text scrolls over their faces: the statements “to beat out the pandemic together/and change the system” and “we unite, we change everything,” surrounded by some of the groups that may be hardest hit by the virus. For a New Haven audience or a national one, it’s a reminder of groups that are working together—across physical distance—to provide mutual aid efforts to residents that may need them most.

.jpeg)

| Margaret Roleke (New Haven, CT), Pandemic/Paramedic. Image Courtesy of the Ely Center of Contemporary Art. Roleke also has a digital solo show right now. |

A few of the show’s artists have taken nature as a starting point, a choice that digs into the parallels between this man-made crisis and the rapid, deliberate destruction of the environment that has been happening for decades. Waking Up Earth, by London-based artist Jackie Brown, makes a natural landscape look more like sepia-toned lungs awaiting the worst. Amy Greenleaf’s Homebound freezes a moment—a plant reaching its leaves toward the sun—and makes it look weathered and old.

Nate Lerner, whose photographs often merit a second look, has added bright pink text to the photograph of a placid lake. The disconnect is jarring and immediate: a vacation landscape is scarred by blocky text, and a bubble-gum-colored warning that “You body/is haunted by/unalterable/forces.” So too in Kate Emery’s Waiting, where the piece’s stillness, like the calm before the storm, may unsettle even the calmest of viewers.

Schmidt said it was important to him to have a show that brought international artists into the center’s orbit—and the center into theirs. As submissions rolled in on their own, he used Instagram to message artists who he saw oceans away, from Baghdad to Bangkok to Benin City.

“We're all in this together in one way or another,” he said. “We're all going to have this overarching situation as a larger global issue.”

| Helga Lebedeva (St. Petersburg, Russia), COVID19 Doctor. Image Courtesy of the Ely Center of Contemporary Art. |

Some are intensely relatable: in Roula Adbuljabbar’s Long Distance Love or Moradi’s Real Superheroes, creations coming pout of Iraq and Iran, one doesn’t need a translator to get the pain, exhaustion, and fear that their subjects may be feeling. Others take closer reading: Greece-based Vasilis Thalassinos has presented viewers with a child-like drawing of a dog, opening the monstrosity that is its mouth.

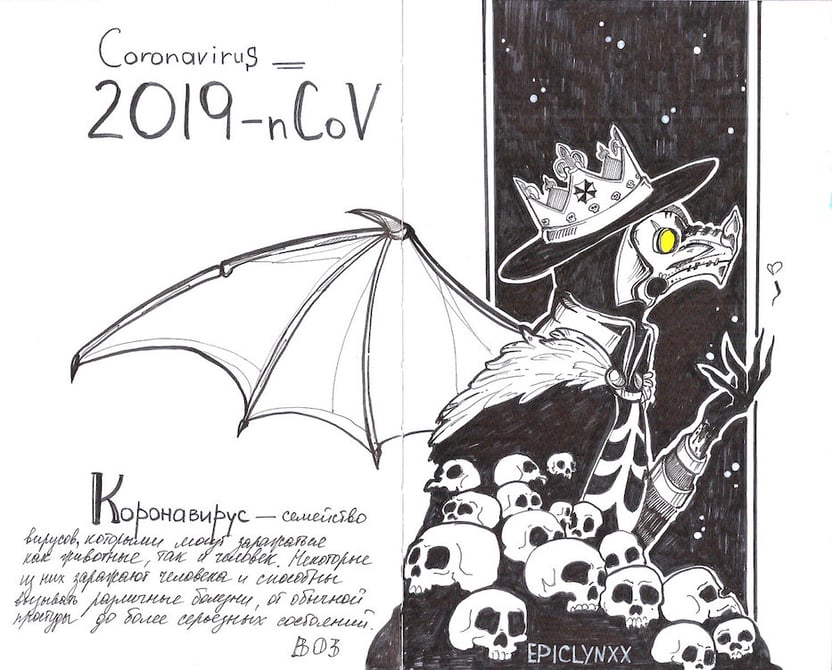

Helga Lebedeva, who submitted work from St. Petersburg, makes a passionate appeal for facts, as a skeletal bat looks beyond the frame from atop a pile of skulls. In an accompanying text, she explains that she has tried to disseminate information from the World Health Organization as a way to quell panic and misinformation.

Schmidt added that he’s excited for the amount of digital programming that the center is rolling out, and savors the Thursday happy hour slots and Sunday critiques. As an artist and a freelance curator, his other part-time jobs have dried up. Before COVID-19, he was working as a dog walker, a website designer, social media freelancer and custodian. Having this job means he can still eat.

“It will keep your head screwed on straight if you have something that's worth it,” he said. “I feel like I have always had a very symbiotic relationship with the work I do at ECOCA, but especially now. The way we all intermingle with each other, it's really rewarding.”

To find out more about digital work at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art, visit their website.