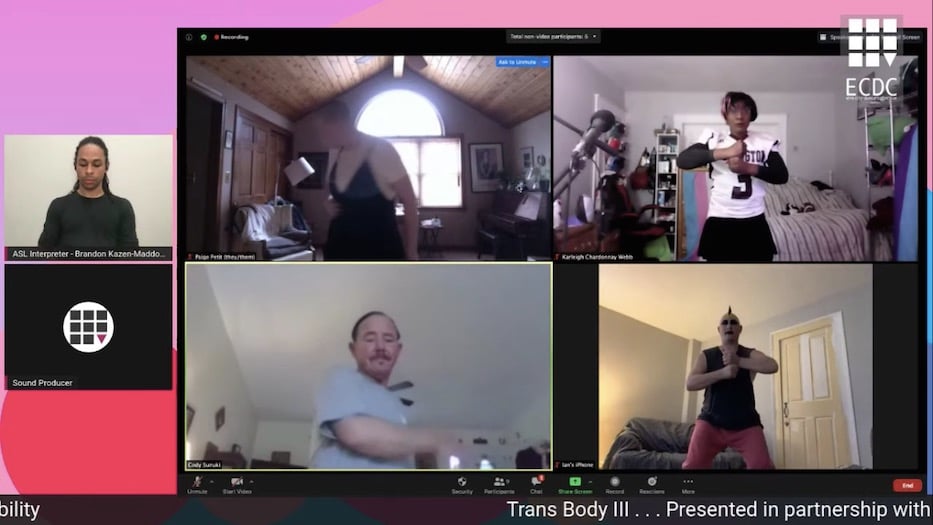

Pictured above is Paige (they/them) in Wednesday's performance. Screenshots from YouTube.

A white Zoom screen sat open, silent and waiting for participants to enter. Piano rose slowly in the background. A voice edged in over the notes: I am near here, but I am far away too. And, it doesn’t matter. The screen flickered to life, open on a dancer beneath a high ceiling, ready to move.

Wednesday evening marked the premiere of Trans Body III, a collaboration among the New Haven Pride Center, Elm City Dance Collective (ECDC), and trans and nonbinary artists in the region. The event coincided with both International Trans Day of Visibility and the Pride Center’s “Trans Week Of Visibility” programming online, which has been presented in both English and Spanish.

“This is what this day is all about,” said Karleigh Chardonnay Webb, a trans artist, journalist and activist who performed Wednesday. “Seeing each other. Being visible to each other. And realizing that each interaction between us as family, as trans family, has ripples. And those ripples can extend far and wide.”

The Trans Body collaboration began in 2019, with performances at the United Church on the Green and Ely Center of Contemporary Art. Last year, partners put the project on hold in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. This March, weekly rehearsals unfolded entirely over Zoom, with four dancers who ultimately stayed for the performance. Wednesday’s dancers included Webb, Cody Suzuki, Page and Paige (they used only their first names), who worked with ECDC co-founders Lindsey Bauer and Kellie Ann Lynch. Two additional participants, G and Clew, did not perform.

Page (they/them) during introductions.

“On this Trans Day of Visibility, we honor our trans siblings, brothers and sisters, through their journeys and a world that often silences those voices,” Bauer said at the top of the performance. She called the project “an effort to provide a creative platform for community members so that stories can be shared, danced, and seen.”

From the moment it opened with a blank screen, the performance explored the act of witnessing and being witnessed. One by one, dancers introduced themselves with their names, pronouns, a descriptive phrase, and corresponding movement. In between, the familiar white of a Zoom waiting screen hung like a curtain, that liminal space between knowing and not knowing, silence and speech, blood and chosen family.

Suzuki embraced themselves with the declaration of “they/them,” said with such rhythm and deliberateness it came across as poetry. Paige placed their fists one on top of the other like heavy stones. Webb extended her arm to its full wingspan and threw her body forward, as if she was delivering an opening pitch at the World Series. Page appeared amidst mentions of the rain, their left arm undulating until it rested, upright, beside their cheek.

Only after each artist danced themselves into being did the in-between Zoom curtain fall, revealing a screen with all four ready to move in unison. The shift doubled as a sort of connective webbing, knitting the four humans together before they began to move in time with each other. Patrick Dunn, executive director at the New Haven Pride Center, said he used multiple screens to pull the performance off.

The device—to remove that virtual time-slicing knife of a waiting room—became as effective as it was affecting. Across four distinct video streams, performers invited viewers into their intimate spaces, their bedrooms and offices expanding behind them. In Webb’s room, a blue, white, and pink trans pride flag hung proudly in the background, beside her bed and bookshelf. In Page’s space, a single beanbag chair waited behind them.

Together in digital space, the four took on each other’s movements, turning a suite of singular actions into a communal, codependent dance. In Webbs’s arms, something about Suzuki’s shoulder-hug became wonderfully unhurried. Page’s riff on it turned regal. Paige took Webb’s outstretched arm, and made it balletic without ever losing force. Dancers reached out towards the camera—and by extension, the audience—as if reaching right through the screen for a hug were wholly possible.

Performers also made clear how rich and kaleidoscopic each trans lived experience is. As piano keys gave way to synthy, propulsive beats and overlapping voices, Page took the virtual stage, their body an unending, deliberate wave. From their box, shoulders dipped and swam through space, arms outstretched. They ushered in Webb, who in turn greeted Paige.

Eyes came up close to the camera, exploring the world beyond the screen. Bodies became untethered, swinging, and bouncing between floor and ceiling. Viewers got feet, ankles, knees, and arms. They got shoes that were pulled on, tied up, and able to walk out of the frame. They got flicked wrists and fingers that curled inward. Together, each segment of a body made up a whole.

Instead of seeing Zoom as a hindrance, artists and facilitators used it as a tool for connection. At one point, the four dancers pulled in stuffed animals, sudden comforts in a world that is not always comfortable. At another, they experimented with reflective surfaces and overhead shots that re-framed their faces.

In front of a cloudy mirror, Paige crouched and swayed from side to side, their eyes locked on their body. In her bedroom, Webb posed beside her flag, the colors bright against a starched white and purple football jersey. Suzuki lifted their hands over their mouth, then let them fly to the sides of their body, fingers wiggling and almost playful. They put on a hat that read “I Am A Man” and then, just as quickly, removed it.

As in previous performances, artists also looked to language, particularly its outer, most economical limits. In a section that featured as much poetry as movement, Page’s words rippled over the frame, flowing through dancers. As they spoke, the waiting room appeared and then lifted once again to Paige moving in time with the words. Webb joined as a dial tone crackled and pulsed in time with the words.

“Undulating. Entangled. Embedded within the social structure of inclusion-ness,” Page’s voice read. “Not here, and yet always been. Acknowledged, but not always spoken. You and I are not so different.”

It comes at a time when the act of being visible is still often met with violent threats, discrimination, and verbal and physical harassment and abuse. This year, International Trans Day of Visibility dawned amidst a wave of anti-trans legislation in close to 20 states across the country. Last year marked a surge in violence against transgender people in the United States and worldwide, made worse by pandemic-fueled isolation. Between September 2019 and October 2020, Transrespect Vs Transphobia documented 350 murders of trans people, most of them women of color, across 75 countries. In the United States, 44 trans people were killed last year, making it the worst year of anti-trans violence on record.

In a discussion after the performance, Suzuki said that they were initially drawn to the performance for its combination of dance, storytelling, and poetry. Before rehearsals, they had never danced. During the performance, they relaxed into their body, and let it take them to new places.

“I never thought it would be possible for me to actually move my body in these ways, so I’m grateful,” they said. “Thank you for the experience, and also for the experience of meeting fellow trans people. With the pandemic and everything, there’s little opportunity to be sharing our stories and our lives. How much fun is this?”

Webb invited fellow trans people to join the Pride Center and ECDC in the next iteration of the project. When Trans Body started, she danced it alone. Then Paige joined, along with artist Finn Lockwood. This year, she watched the project more than double in size during rehearsals.

“We hope that some of you, maybe all of you, who are trans who are here, on this Day of Visibility, come back for Trans Bodies IV,” she said. “And not be on that side of the screen, but be on this side of the screen.”

To learn more about the New Haven Pride Center, click here. To learn more about Elm City Dance Collective, click here. If you or someone you know is looking for trans support, crisis management, or community, Trans Lifeline is accessible 24/7. The Trevor Project offers 24/7 confidential support for LGBTQ+ youth in crisis. Other resources include The Trans Women of Color Collective, The Sylvia Rivera Law Project (SRLP), and The National Center for Transgender Equality.