Faith & Spirituality | Music | Arts & Culture | New Haven Museum | Arts & Anti-racism | Heritage Chorale of New Haven

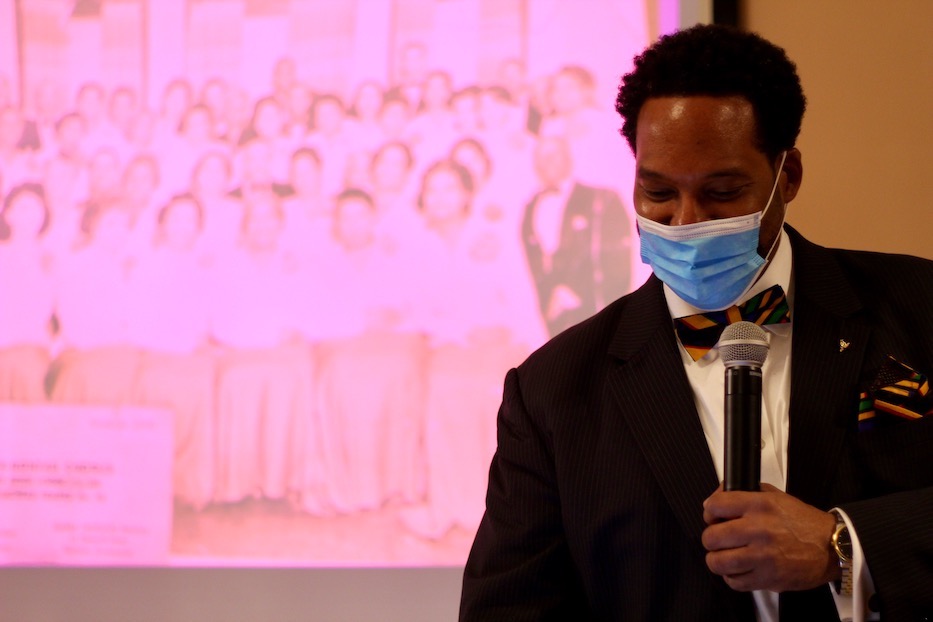

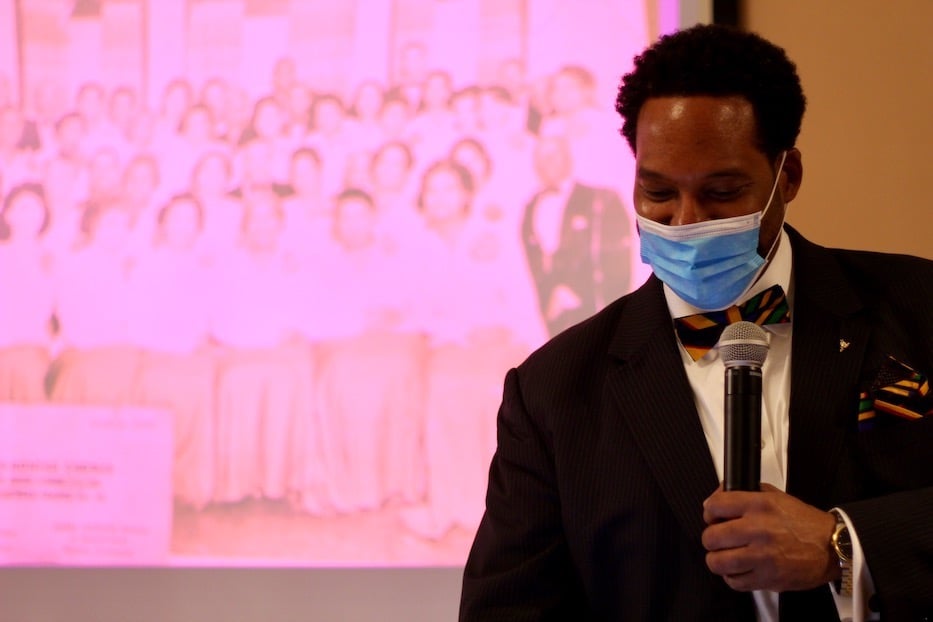

Jonathan Quinn Berryman Wednesday night. Lucy Gellman Photos.

At first, dozens of voices floated from the speaker, filling the second floor of the New Haven Museum. Lift every voice and sing/Till earth and heaven ring! they started, splitting into a harmony that sprinted forward. Ring with the har-mo-nies of liberty. From somewhere near the middle of the room, half a dozen live voices joined in, the sound rolling towards the ceiling. Between each breath were decades of Black New Haven history.

That soundtrack belonged to “Six Degrees of Separation Through Music,” a long-awaited talk and celebration of the Heritage Chorale of New Haven (HCNH) from director Jonathan Berryman at the New Haven Museum at 114 Whitney Ave. First scheduled for March 2020, the presentation rang in a quarter century of joyful music making for the chorale, which started in a Fair Haven living room and has grown across the city.

Despite the damp, still-slushy sidewalks, over four dozen attended. Many have been with the chorale for the entirety of its 25 years—and are hoping to see 25 more as they return to singing after an unwelcome pandemic intermission.

The Heritage Chorale c. 2004. Contributed Photo.

“This is reminiscent for me of being at home with my family,” Berryman said as a final few attendees trickled in, and he pulled up a PowerPoint with a bright, sunshine-yellow page and early HCNH recording of “I Don't Feel Noways Tired” on which he was the soloist. “You’re part of this exploration.”

The idea—that most New Haveners have a point of connection to the chorale—comes from the birth of the chorale itself. In 1998, Berryman had just finished his graduate work in choral conducting from the Yale School of Music. During the week, he was a music teacher for the city’s public schools, where he still works today. On evenings and weekends, he worked as the choir director and organist at Varick Memorial AME Zion Church on Dixwell Avenue.

By then, he very much had a foot in both Yale and non-Yale worlds. Through his studies at Yale, he had served as the assistant conductor of the Yale Camerata, through which he knew conductor Paul Mueller. Through his time at Varick—and later Immanuel Missionary Baptist Church and the Bible Gospel Center—he also knew of the city’s Black choral legacy, including the Saulsbury Chorale, Rock-Hontas Chorus, and New Ensemble.

So when Mueller, by then leading the New Haven Chorale, called him that year to talk about a potential collaboration, it piqued Berryman’s interest. He had no idea that the group’s bright spirit and dedication to music-making would last for 25 years.

At the time, the New Haven Chorale wanted to perform William Grant Still’s “And They Lynched Him On A Tree,” a piece of music that requires a white chorus, a Black chorus, and two soloists—a Black contralto playing the victim’s mother, and a male narrator. Berryman called Herbert Scott, whose time singing in Black choruses in New Haven reached back decades.

Scott “made some calls” of his own, Berryman remembered. In March 1998, Berryman invited singers for an initial meeting at his small apartment in Brewery Square. He had no idea what to expect.

“Thirty people showed up!” he recalled, his eyes sparkling as attendees laughed at the memory. “I was overwhelmed, but there was room."

The group started rehearsing at Varick, where Berryman was working and had access to free space. Even in its early days, the chorale comprised generations of New Haven music history: music educators, Varick members, former members of the Rock-Hontas Chorus, vocalists who shone in their own church choirs, and wanted another space to sing.

When he learned that the concert would be at Woolsey Hall, Berryman marveled at music’s ability to bridge communities within a city of contrasts.

“It created a town-gown connection that did not exist before for many Black singers in New Haven,” he said. “When you’re on the stage looking out, that’s very different than sitting in the seats looking up.”

The Heritage Chorale c. 2008. Contributed Photo.

It was the beginning of something built to last, Berryman discovered. When the Heritage Chorale performed at Woolsey in January 1999, members wanted the music to keep going. Berryman—this young, charismatic, bright-eyed conductor—did too. That year, they performed Still’s sweeping work again with Coro Allegro in Boston, after a Black choir backed out at the last minute. It marked the beginning of a regional partnership that has lasted through today.

In New Haven, their footprint was also growing. In the summer of 2000, they were part of Neely Bruce’s “Convergence” during the International Festival of Arts & Ideas, what Bruce at the time referred to as a “collision of sound” on the New Haven Green. By a 2001 collaboration with the Yale Camerata, they had moved from Varick’s Dixwell Avenue sanctuary into Immanuel Missionary Baptist Church on Chapel Street, where Berryman was working as the organist.

As they performed across the city, their list of collaborators and venues grew. While planning three of their own annual concerts, Heritage Chorale members worked with the Madame C.J. Walker Mansion, Mt. Zion Seventh Day Adventist Church and the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. among other spaces. At home, they performed with the New Haven and Hamden Symphony Orchestras, Bethesda Lutheran Church and Southern Connecticut State University and in the Town of Guilford.

By their 15-year anniversary, that list of collaborators had grown to over two dozen. In the process, singers were making New Haven music history, Berryman said. They worked with public school teachers and steel bands, symphony orchestras and house museums, small churches and big state buildings. They helped revive performances of Black Nativity at Long Wharf Theatre. He watched as people including Dr. Tiffany Jackson, Malcolm Welfare, Jaminda Blackmon and members of the Unity Boys Choir grew into themselves before his eyes.

They helped other organizations ring in their anniversaries without ever knowing that they would make it to a quarter of a century. Around 2008, the chorale changed its rehearsal home to the Bible Gospel Center, and kept singing. In 2019, they returned to Boston for a 20-year anniversary concert with Coro Allegro. Berryman is sometimes amazed, he said, by how much time has passed, and how quickly.

“I accept the fact that I’m not as young as I used to be,” he said, laughing hard enough that his shoulders bounced up and down. “I don’t even know that we had email when we started … And that first phone call was on a landline.”

When Covid-19 hit in March 2020, the group stopped rehearsing. Preparation for Berryman’s talk, then scheduled for that month at the New Haven Museum, came to a sudden halt. Around him, the world was shutting down; news reports later identified a choir rehearsal in Washington State as one of the first superspreader events. Members learned how to exist in isolation. Some stopped singing; others kept the music flowing for their students and colleagues.

Almost exactly three years later, they are thinking about how to come back, Berryman said. With the exception of a virtual collaboration with Coro Allegro in 2021, they haven’t had a project to work towards. Now, Berryman is in the process of planning a number of workshops simply to get them back together. From the second row of the audience, Wooster Square champion Elsie Chapman stressed how much she also longs to hear them in concert again.

“I think our first job is just to provide an opportunity for people to sing together,” Berryman said.

“The Most Wonderful Experience Of My Life”

Aubrey Tompkins. Lucy Gellman Photo.

As Berryman sat back behind his laptop, several longtime members of the Heritage Chorale came forward to tell attendees what kept them coming back to the group. One of the first to the mic was Harriett Alfred, who began teaching music at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School the same year of that fateful meeting in Berryman’s living room.

She took attendees back to March 1998, as she squeezed into that Brewery Square apartment to sing through “And They Lynched Him on A Tree” for the first time. She looked around, and found a community. Two and a half decades later, she said, the group has helped her grow as both a vocalist and a music educator.

“I found it amazing that there were so many people that hungered to come together and keep music that is generally associated with the Black church alive,” she said. Smiling, she remembered watching Berryman grow as a musician, and taking some of his technique as a composer into her classroom. The road goes both ways, Berryman later said: he also learns from his members.

“This choir has been a wonderful experience in my life,” she said. “I am grateful that Jonathan had the vision, opened his doors, and allowed us to come in.”

Aubrey Tompkins, a retired educator who was also in that first meeting, praised Berryman’s leadership in keeping the group together. Now the choir director at Mt. Zion Seventh Day Adventist Church, Tompkins was born and raised in Memphis, Tenn. and came to New Haven as an army medic in 1959. When he found the chorale, it was like a piece of his life fell into place that had been missing.

He noted how transformative it was to sing from the stage at Woolsey Hall, where he had been going to concerts for decades. After years of wondering what it would be like to perform there, he had his answer.

“We have had several organists in my church and I hate to say it, but he’s my favorite,” he said to laughs. “I just want to say, the lord gave Jonathan to New Haven.”

Many in the group honed in on the ability to build community through song. Alto Joyce Patton, a transplant from South Carolina who met Berryman in his role as music director at Varick, called the group “the most wonderful experience of my life.” Self-described “shy soprano” Valerie Parks remembered how the group helped her come out of her shell. Richard Ford, a former member of the Yale Camerata who sings tenor and bass, said he sees it as the culmination of his musical experience.

“When I joined the Heritage Chorale, I was just lifted,” said Valerie Burroughs, who jokingly referred to herself as “Valerie Number Two,” “We come together because we all love Jesus and we want to make it to heaven.”

For other members, the connection is much closer than six degrees of separation. Jaminda Blackmon, now an educator at Wexler-Grant Community School, joked that she was a fairly "new" member—meaning that she joined 18 years ago, For her, it was a source of connection not only to other Black New Haveners and to music she could feel in her bones, but to her own parents, who joined after seeing the joy that it gave their daughter.

She remembered hearing the chorale at one of their early concerts, and instantly recognizing the repertoire as music that she had grown up with.

“I breathed for the first time in, I don’t know how many years,” she recalled. She joined soon thereafter. Two years later, her parents joined too. It let her redefine their relationship to each other.

That sense of belonging echoed throughout the evening, but perhaps nowhere as strongly as in clips of music itself. At one point, Berryman pulled up a recording of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” arranged by Chattanooga-based composer and conductor Roland Carter. Over a flurry of keys, voices came swooping in, sailing through the room. They wrapped around the museum’s second floor rotunda, growing louder as chorale members in the audience joined in.

“The Heritage Chorale has been part of my being connected to New Haven,” Berryman said. “Both in terms of music making and in terms of personalities.”

Learn more about the Heritage Chorale of New Haven here. Watch the full talk above.