Fair Haven | Arts & Culture | Film & Video | Jaigantic Studios | Commission on Disabilities

Buster during Monday night's presentation. Zoom Screenshot.

Visibility aids. Access to reliable transportation. Job opportunities for people with autism and ADHD. An eye toward physical and developmental disability that doesn’t stop at wheelchair ramps. And a liaison in the main office who is there for questions, support, and advice.

Members of New Haven's Commission on Disabilities brought those suggestions to Jaigantic Studios Monday night, during a visit from Jaigantic Chief Impact Officer Jackie Buster at the group's monthly meeting. As Jaigantic makes its pitch across the city, Buster said she wants to ensure that the studio is open to job applicants and employees of all abilities. Fourteen people attended the meeting, held on Zoom.

Jaigantic is the brainchild of actor and martial artist Michael Jai White. It is currently running its offices out of an ADA-inaccessible building in Shelton, with plans to expand to River Street in Fair Haven as early as this winter. Read more about its plans for Fair Haven here, here, here and here.

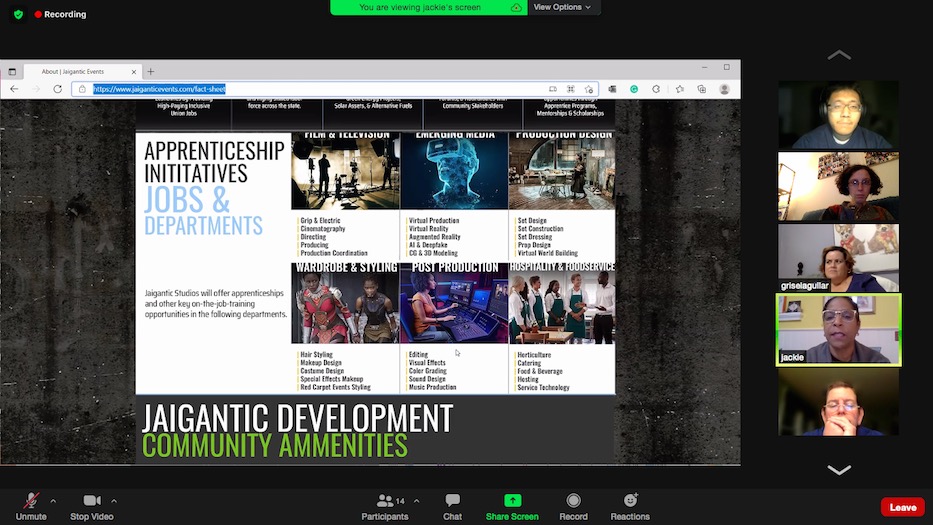

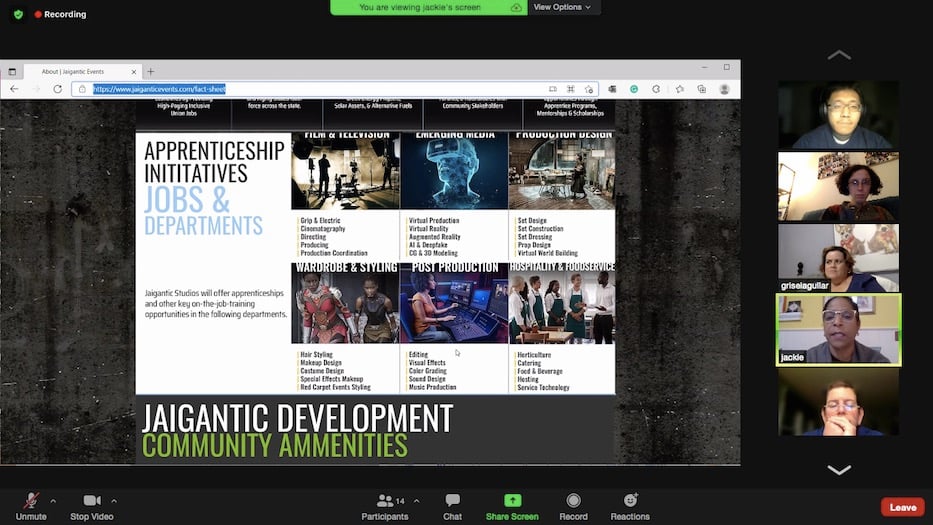

“Our mission, I believe, speaks to diversity,” Buster said at the top of the meeting, pulling up the studio’s mission statement in a bright, crowded and colorful presentation. “When I first spoke to several of your folks, we talked about this, and it’s built into our fiber.”

Buster framed Monday’s conversation as a chance to learn from members of the commission before Jaigantic brings its work to Fair Haven. Currently, the studio has a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the City of New Haven for a parcel of land at 46/56 River St., and a city-owned parking lot nearby 112 Chapel St. It is finalizing its Development and Land Disposition Agreement (DLDA) with the city, after which it plans to begin work.

In the meantime, Jaigantic staff and representatives are working out of a temporary studio on Constitution Boulevard in Shelton. Buster said that the space, which holds two sound stages and is located in a zero-entry building, is not yet in compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act—but that the studio has plans to change that. For the first of many times during the night, she focused exclusively on both staff and visitors who might use mobility aids.

“We can now start renovating bathrooms, and kitchen areas, and doorways,” Buster said. “We are cognizant of what we need to be able to do to get our building up to par, even if it’s just for a visitor. When it comes to employees, the same thing.”

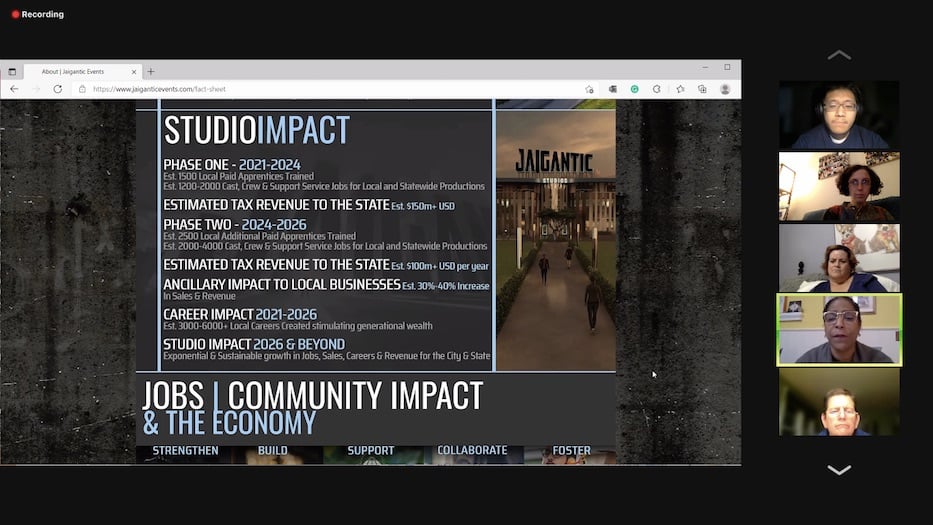

Monday, she framed Jaigantic’s growth as a pathway to job training and economic development in both the city and the state. She outlined jobs in both operations and studio production—building and striking sets, doing lighting, sound, direction, production, and acting—that Jaigantic staff envision making as accessible as possible.

The first, she said, encompasses “whatever you can imagine,” including legal work, an accounting department, information technology, positions in food service and hospitality, and a medical team on site. For the second, the availability of remote work and virtual world-building opens the field to people who may need at-home or hybrid accommodation.

“Wherever someone can imagine themselves, we want to be able to work with them to fulfill their dreams and to try to do as much as we can to get them in our doors, get them trained, and get them job ready,” she said.

“A director can be in a wheelchair, right?” she continued while scrolling quickly through potential jobs. “A director just needs his brain and voice to be able to speak to whatever he or she wants done. Same thing goes for producing.”

No sooner had she finished than questions bubbled up from the group. Commissioner Linda McDonough, who lives in New Haven and works as a special education teacher in Bridgeport, noted that Buster’s presentation focused heavily on adults with physical disabilities, from the mentions of doorway width to wheelchairs. She wanted to know about opportunities for those with cognitive or developmental disabilities.

Of the 61 million Americans living with a disability—just over 26 percent of the U.S. population, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—13.7 percent face difficulties with mobility. Over 10 percent face a cognitive disability, while 5.9 percent live with hearing impairments and 4.6 percent face vision-related disability.

“What about other kinds of disabilities?” she said. “Suppose somebody has autism or ADHD. Is there a mentor on site?”

Buster paused. “At this, point, no,” she started. She quickly added that one of the studio’s investors has pushed staff to consider what that infrastructure would look like. His son is on the autism spectrum and currently working for the Hamden Public Schools. He’s asked Jaigantic to think about how he could thrive in the fast-paced, movie-making "studio creator district" that its leadership has envisioned for Fair Haven.

“We need to make sure that we are prepared and that our staff is trained, that they’re educated to know that there’s something they should be looking out for,” Buster said. In her tiny box at the righthand corner of the screen, McDonough nodded.

“We’re very transparent in saying we don’t know what we don’t know,” Buster added. “Our plan is to put together a plan that makes sense and that’s compliant.”

Commission Chair Billy Huang, a biologist and housing advocate who founded the Source Development Hub in 2018, saw an opening. In his own work, Huang works to address housing insecurity among people with disabilities. He asked Buster if Jaigantic had considered training opportunities specifically for members of the disabled community.

Huang noted that the unemployment rate is currently at 12 percent for individuals with disabilities, compared to five percent for the general population, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. It is actually higher than that for women with disabilities, at 13.2 percent for 2020.

With that number in mind, he’s particularly interested in training programs geared toward high schoolers and recent graduates. Annie Harper, a commissioner who is also the project director for the Citizens Community Collaborative at Yale, later extended that question to people who had previously been incarcerated.

Buster responded that Jaigantic recently met with New Haven Works, which seeks to address chronic unemployment with workforce development programs and local jobs. While the studio has not yet designed a training program specifically for people with disabilities, she said it would be open to it. She pointed to Jaigantic’s year-long apprenticeship program, which puts young people into unionized production positions.

“This is the perfect time to be able to inform us” of what the studio is missing, she said. “Because we want to do what’s right.”

In response to Harper’s question she added that White, who grew up in Bridgeport and ran a karate studio on Grand Avenue, “believes in second chances.” According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 38 percent of people in the carceral system have at least one disability. The same data shows that 24 percent of prisoners report getting a diagnosis of ADHD “at some point in their life.”

Buster listened, taking everything in between questions that came in rapid succession. City Director of Disability Services Gretchen Knauff suggested adding a disability services liaison to Jaigantic’s human resources roster. Echoing fellow commissioners, she pointed to misconceptions that often surround people with cognitive differences.

“As you said, you don’t know what you don’t know," she said. "But vocationally, there are a lot of individuals who don’t have physical disabilities—who have learning disabilities, brain injuries, etcetera—and many of them really excel in the hands on.

“What I’m hearing is you have apprenticeships and internships, and that would be a real boon, she continued. “But you have to ... there should be someone who’s aware of and can help you think about that. There are a lot of things people can do. There’s a set of expectations, sometimes, that are much lower than what really can be achieved.”

Commissioner Sally Esposito, who served for years as the director of Yale's Office of Disabilities, noted the importance of both comprehensive transportation and accessibility aids for Jaigantic’s website and marketing materials, which are bright and packed with information. Huang added a suggestion of an advisory group to workshop language, for which he volunteered the commission. Knauff jumped back in.

“I’m really interested in making sure that you have people who know how to support people with disabilities and also who provide the opportunities,” she said. “ What’s just as important as the vision is really what’s going to happen. And let’s get people working.”

The next meeting of the Commission on Disabilities is Nov. 8 at 6 p.m. Access the meeting and the agenda here.