New Haven Free Public Library | Westville | COVID-19

The library last Wednesday, as a patron waited outside for curbside pickup. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Tennille Murphy has relied on Mitchell Library since she moved to Westville over 20 years ago. When she was a college student, it was where she knew she could find WiFi or go when she had computer trouble. As a mom, it was one of the first places she took her daughter. And as the owner of a small business, it has become a haven for cooking classes and community building.

If it closed, she doesn’t know where she would go.

Monday night, over 30 New Haveners slammed Mayor Justin Elicker’s proposed “Crisis Budget” before the New Haven Board of Alders’ Finance Committee, in the first of three public hearings around the city budget. One of two potential budgets proposed last week, the $589.1 million "Crisis Budget" would raise taxes 7.75 percent and shutter Mitchell Library, the East Shore Senior Center, and the fire station at 350 Whitney Ave. Mitchell is one of five branches of the New Haven Free Public Library (NHFPL).

A proposed $606.2 million “Forward Together” budget leaves those resources intact, and banks on $53 million from Yale University and the State of Connecticut. Read about both budgets here and here. Access the budgets in their entirety here.

Monday, New Haveners came from all corners of the city to testify against the mere thought of shutting down the library, pointing to its role as a lifeline in the community both before and during the Covid-19 pandemic. Named after author, farmer, and early Westvillian Donald G. Mitchell, the library has become an anchor in the neighborhood for its resources and community partnerships, which range from cooking classes to landscaping work with adults at the Chapel Haven Schleifer Center.

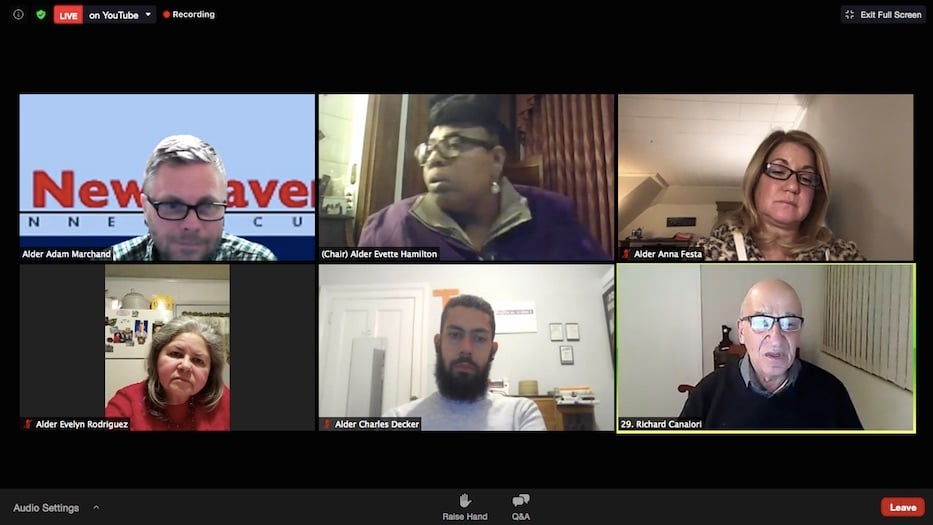

Clockwise, from top: Lizzy Donius, Andrew Giering, Rebekah Fraser, Katie Jones, Tina Menchetti, and Richard Canalori.

In testimony after testimony—some written and delivered on the spot—attendees pressed the importance of asking Yale to raise its voluntary annual contribution to the city, which was most recently $13 million. Currently, close to 60 percent of the city’s grand list—that’s $8.5 billion in property value—is tax exempt. Over 40 percent of that is Yale University; just over 14 percent of it is Yale New Haven Hospital. While the city is projecting a $66 million deficit, Yale is reporting a $203 million surplus and $31.11 billion endowment.

“While the possibility of PILOT funding gives us reason for cautious optimism, I am stunned by the threat of closing Mitchell Library to save less than $200,000,” said Andrew Giering, an NHFPL board member and public defender who spent his 34th birthday testifying on Zoom. “During this time of remote work and learning, the library has helped level the playing field in our very unequal city by ensuring free internet access for everyone.”

Currently, the New Haven Free Public Library receives about $4.5 million from the City of New Haven. Giering noted that it is trailing other large and mid-sized cities in the state, particularly when compared to the $7.8 million Bridgeport puts aside for its public library, $9.9 million for the Stamford Public Library, and $12.4 million for the Hartford Public Library.

And yet, he said, it does a lot with what it has: it has continued programming, opened curbside pickup, grown its electronic resource collection, and begun distributing WiFi hotspots and Chromebooks during the pandemic. One full year before Covid-19 was a household term, the library snagged the 2019 National Medal for Museum and Library Service through the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS).

“This means that New Haven’s library system, through the incredibly hard work of our staff, has reached a level of national recognition that surpasses any other city department,” Giering said.”The staff has accomplished this not because the Library is so well-funded, but despite that it is, in fact, severely underfunded.”

Lizzy Donius at a meeting of Mayor Justin Elicker's Transition Team in December 2019. Lucy Gellman Pre-Pandemic File Photo.

No sooner had Giering finished speaking than a parade of heated bibliophiles waited for their turn to speak. Lizzy Donius, who currently serves as the executive director of the Westville Village Renaissance Alliance (WVRA), noted that the overall savings of closing a library branch is $188,000—roughly three-ten thousandths of the city budget. She looked to the words of longtime library and NHFPL Foundation board members Elsie Chapman, who has often spoken on the library as a great equalizer.

“The five thriving branches of the New Haven Free Public Library reach every demographic in our city, every single day, and we reward them with reduced hours, unstable funding, and now the threat of closure,” she said. “We should aim to invest in and grow our libraries into the fully funded, thriving community centers they are well on their way to being. Even with cold, hard, budgeting glasses on, this is a baffling suggestion.”

Donius added that she sees significant economic harm in the threat of closure, which would leave Westville Village with an empty building at the center of town. The library’s Harrison Street building is just up the block from lively shops, cafes, and restaurants that have continued to see foot traffic through the pandemic.

If the building were to become a shell of itself, she estimated that the damage would be far greater than $200,000. On the flipside, she said, a fully funded library system could be an economic driver for the city.

“Threatening to close a library branch … even if it is a worst case scenario, is incredibly damaging,” she said. “More from Yale, yes, and more from the state, but do not come for the library. It paints the library as a luxury, and if we do not respect the sacred role our libraries play in our city, democracy, and public life, our libraries will be forever undervalued, underfunded, and underperforming.”

Author Rebekah L. Fraser pictured at Manjares in 2018. Lucy Gellman Pre-Pandemic File Photo.

Author Rebekah L. Fraser began her testimony with a recap of how difficult the past year has been for artists, who are often shut out of Covid-19 relief funding because they do not qualify for the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) in the same way a business would. Before the pandemic, she was working with former Branch Manager Sharon Lovett-Graff to organize writing workshops at the branch. When Covid-19 hit New Haven, those fell through.

In the past year, she’s leaned on the library for its hotspot lending program. She urged alders to think about the number of people in the neighborhood who don’t have access to safe and reliable transportation, who rely on the library for books, movies, and tech devices.

“As an author with four published books, I have found great relief from the Mitchell Library, both before and after the pandemic,” she said. “It’s been a great opportunity to share my work with a local audience with public readings and events … it would be devastating to not have my local library branch.”

.jpg?width=933&name=Earth_Building%20-%202%20(1).jpg)

Katie Jones in May 2019. Lucy Gellman Pre-Pandemic File Photo.

Katie Jones, who lives within walking distance of Mitchell Library, urged the Board of Alders to vote against any measure that would so much as jeopardize the future of the branch. Jones praised the library as a safe, resource-rich space for young people, city residents seeking employment and tech help, and those looking for free, collaborative programming. She called on Yale to “pay up after centuries of theft and abuse of folks on this land.”

“I’m amazed at the absurdity of this item on the crisis budget proposal,” she said. “And I just have to wonder what else is going on to occupy our energy and time and attention defending what many of us, as many people have named already, can consider a miracle that is the New Haven Free Public Library system.”

She also expressed concern over the $43 million reserved for the New Haven Police Department, an item that she sees as falsely equating law enforcement with both public safety and public health. She urged the city’s Board of Alders to consider defunding the police or considering alternatives to law enforcement.

“Making that equation is misguided and dismissive of reality, and much research that shows public safety is most dependent on mutual aid support, access to housing, food, education, and of course freedom of movement.”

Several educators also came out in defense of the library. A longtime resident of Westville who now lives in City Point, Richard Canalori grew up within walking distance of Mitchell. As a former teacher at Mauro Sheridan Interdistrict Magnet School, he recalled the number of schools that would take field trips to the library’s Harrison Street building.

In under three minutes, he gave alders a crash course in Donald Mitchell’s life and legacy in Westville. He shouted out libraries as home to more than books—they are technology hubs, printing and photocopying service centers, social and educational gathering spaces and places where children and adults alike can find free programming.

“The village was designed specifically so that people had access to the library, to the church, to the fire department, right in that central spot,” he said. “It is literally and figuratively the heart of Westville. It is the soul of Westville. To take away the Mitchell Library would be a disaster.”

Tina Menchetti, who has been the art director at Chapel Haven for 25 years, told alders that closing the Mitchell Library would be catastrophic for her students. At Chapel Haven, Menchetti works to prepare adults with developmental and cognitive disabilities for independent living in the surrounding neighborhood and city. The library has become a vital resource to residents and staff alike.

“It’s such a hub of activity,” she said. “It’s a sense of community for our students. It’s the heart of the neighborhood. They gather there, they use the internet—a lot of these students don’t have the ability and the access to technology that they do at the library there. It’s a real gathering place for them, as a neighborhood … students have such a sense of pride and purpose when they’re there.”

Murphy leads the Kids Kook Association, including a virtual demo last summer for Juneteenth 2020.

Delivering one of the last testimonies of the evening, Murphy said the library “has been a vital resource to myself and my family.” As the founder and executive director of Kidz Kook Association, Murphy has partnered with the library on live cooking demos and events that center food, nutrition, and community engagement. As a mom, she has come to rely on its in-person and digital programming.

“The library will stay in the community and thrive,” she said. “There’s not many resources for the youth in this side of the town. So we’re just really asking—how could we look at this budget, how could we get together and have Yale pay what’s due to us, so that resources like the library won’t be stripped out of communities?”

The next hearing is scheduled for March 30 at 6 p.m. Members of the public may send public comment on the budget to publictestimony@newhavenct.gov at any time.