Books | Dixwell | Mardi Gras | Poetry | New Haven Free Public Library | COVID-19

Betts, Eady and Derricotte Tuesday night. Screenshot via YouTube.

Reginald Dwayne Betts had a routine each time he heard the book cart squeaking through the Fairfax County Jail. He had lost the ability to wear clean contact lenses, because the prison was unsanitary. He didn’t have access to an optometrist or a pair of frames. Instead, he would pick books out by the feel of their spine, and then hold them up next to his face when he was ready to read. It was the closest thing he had to a magnifying glass.

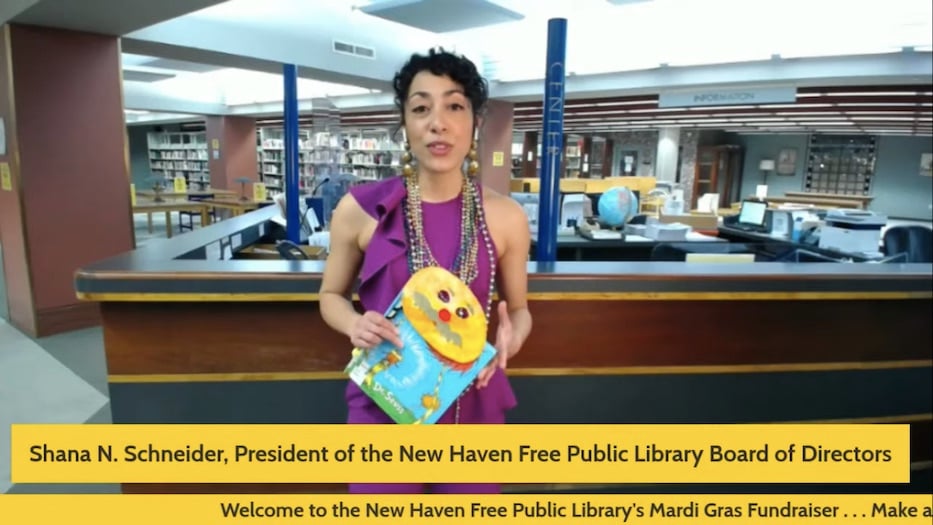

Tuesday night, Betts—now a pioneering lawyer, poet, and criminal justice reformer—brought that story to the New Haven Free Public Library (NHFPL) during its 19th annual Mardi Gras fundraiser, moved online due to the Covid-19 pandemic. In just under two hours, the event featured a conversation between Betts and Cave Canem Co-Founders Toi Derricotte and Cornelius Eady, as well as a salute to longtime library champion Elsie Chapman. Chapman most recently spearheaded a four-year, $2 million campaign to reimagine the Stetson Branch in its new Q House home.

By the end of the night, the event had raised $48,500 for the library. Lauren Bisio, director of advancement for the New Haven Free Public Library Foundation, said that funding will go towards growing the library’s collections, particularly investment in “e-books, audiobooks, and other e-resources that people can access from home.” Those are often much more expensive in electronic and audio form than they are in print, which has left the library scrambling to keep up after a 30 percent cut to its collections funding in the city budget last year.

“We’re not gonna let Covid keep us down,” said NHFPL Foundation Board Chair Michael Morand. “And inspired by our friends in New Orleans who have swerved so beautifully with house floats and other new traditions, we’ve decided that the show will go on this year, virtually.”

With cameos from musicians, public history nerds, current and former elected officials, and local bibliophiles of all ages, it doubled as a stunning love letter to both the NHFPL and libraries across the country, that keep the sputtering, low hum of democracy alive. Throughout the night, attendees spoke to the pivotal, often intimate role libraries play in their lives.

With cameos from musicians, public history nerds, current and former elected officials, and local bibliophiles of all ages, it doubled as a stunning love letter to both the NHFPL and libraries across the country, that keep the sputtering, low hum of democracy alive. Throughout the night, attendees spoke to the pivotal, often intimate role libraries play in their lives.

Betts, who attended Cave Canem when he was in his 20s, traced his relationship with libraries back to the late 1990s. As a teenager, Betts was incarcerated for a carjacking that carried felony charges and was tried as an adult case, despite the fact that he was only 16 at the time. While he was in solitary confinement, the poets Etheridge Knight and Lucille Clifton were two of the voices who got him through.

“She has so much range in the work, and so much capacity,” he said of Clifton. “And so much contrariness. In a generation when everybody was renaming themselves, she goes ‘my name is Lucille!’ And it was profound. You know, I felt like I was in a dark spot and I had to figure out how to be me, and reading her work gave me that agency.”

Libraries became his lifeline. There was the library cart, bearing books that he had to hold close to his face—Tuesday night, he held up a copy of his poetry collection, Felon, to demonstrate—if he wanted to read them. He found that in the same way anthologies led him to individual poets, libraries led him to anthologies.

Derricotte’s work jumped from a page of Clarence Major’s The Garden Thrives. Through anthologies, he found Eady’s second book and wrote a letter to the poet, which Eady never received because it was sent to an old university address. He immersed himself in Elizabeth Alexander’s 2004 The Black Interior, which led to his discovery of the Interlibrary Loan system.

Years later, when he met Alexander for the first time, he asked her for a book. She gave him her reader’s copy of The Black Interior, complete with marginalia and thin sticky notes sticking out of the pages like little blue wings. Tuesday, he held it up for listeners to see as he spoke.

"I feel like America doesn't recognize the power and the strength and the intelligence of poets," he said. "And the actual culture building that poets practice."

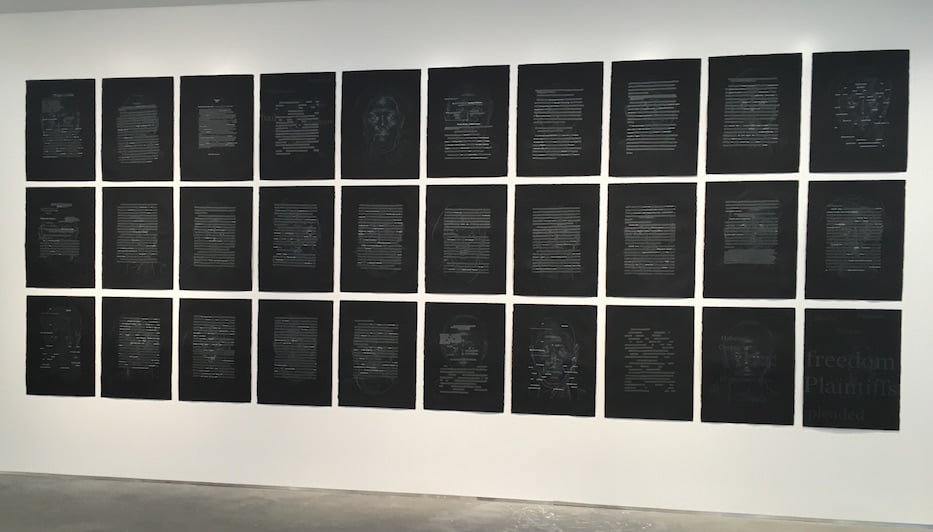

Titus Kaphar and Reginald Dwayne Betts' Redaction installed at NXTHVN in August 2020. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

He is now bringing that fierce love of and belief in libraries to the Million Book Project, a collaboration between the Mellon Foundation—of which Alexander is the executive director—and the Yale Law School Justice Collaboratory. The project seeks to place 500-book collections—Betts refers to them as "freedom libraries"—in 1,000 medium and maximum security prisons.

He said it is inspired by his own experience: for eight and a half years, "I was only close to a bookshelf if I was in the library." He wants the freedom libraries to live within carceral housing units, so they are more readily accessible at all times. Tuesday, he, Eady and Derricotte built a kind of dream bookshelf that included Amiri Baraka, Alexander, Yusef Komunyakaa, Allen Ginsberg, Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, Lucille Clifton, and Cave Canem alumni Jericho Brown and Tracy K. Smith.

Both Eady and Derricotte unspooled similar stories that jumped from Detroit to Rochester to Pittsburgh. As a kid growing up in Rochester, New York, Eady didn’t have many books at home. Instead, he trekked to the Rundel Memorial Library building downtown, where thousands of titles sat waiting for his young eyes. At the entrance, there were two coin-operated machines. One dispensed pencils. The other, pads of paper.

"So I would go in and put in my nickel and put in my quarter, and sit down at one of the great big desks and dream that one day, I'd write something that would allow me to have a book in the library at some point," he recalled. “So libraries mean a lot to me.”

During those years as “a baby poet,” he found Robert Bly's The Light Around The Body neatly shelved in the poetry section. He fell in love with Bly's verse, each line economical and still rich with imagery. A quick peek inside the cover showed that nobody had checked the book out for quite some time. Eady "liberated the book," a move for which he was later chided by Bly himself when the two were in conversation with each other on a cable show.

"I thought it was going to be so damn impressive, and he was like 'you stole the book!?'" Eady said, laughing as his eyes lit up behind his thick glasses. "I wanted my idol to understand how deeply I loved this book. You get so in there ... because that's what you do."

As poetry was nurturing Eady’s soul in Rochester—and later, as a shelver for the Princeton University Library, and then as a teacher and co-founder of Cave Canem—Derricotte was a kid in Hamtramck, Mich., trying to fill her afternoons after Catholic school. The Detroit Institute of Arts and Detroit Public Library, a Cass Gilbert building that rises like a marble palace off of Woodward Avenue, became her de facto babysitters. By the time she was eight, she had started to discover its grandeur, from lunette and walls murals and vaulted ceilings to the books that lived inside rooms upon rooms.

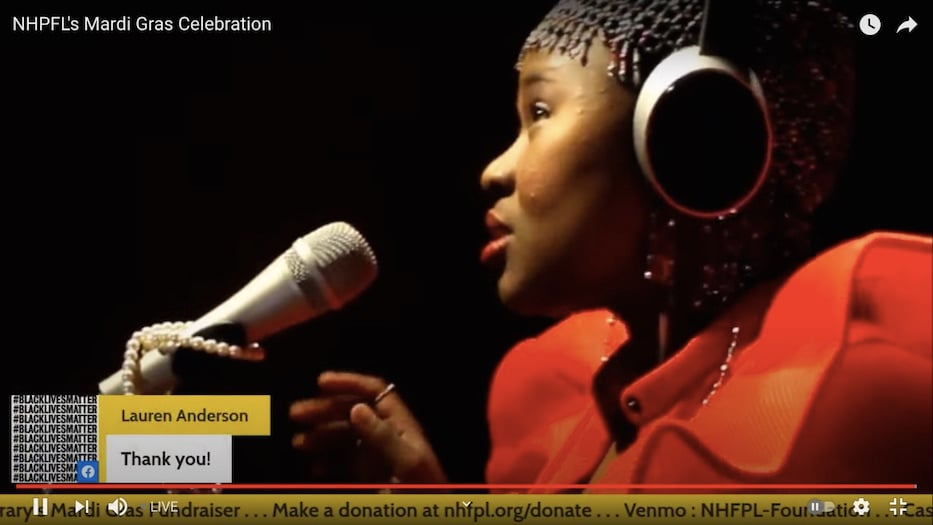

Thabisa, who performed during Tuesday evening's festivities.

"Entering the library felt like I was entering, now I can describe it, almost like a room in myself that had a special something that I recognized as for me,” she said. “I did a lot of figuring out what I was supposed to do to make sure that I was treated okay, or I wouldn't get in trouble, but when I walked through those doors, I had the sense of it being ... almost like the place in my brain now where I go when I'm writing a poem."

Her love for the library fed her interest in poetry. When Derricotte was in her twenties and living in New York City, she read Sylvia Plath's Ariel for the first time. The book transformed her understanding of what poets can do with their control of language, she said.

"I didn't know that there was any place in this world that anger could be expressed safely,” she said. “In my childhood, you could be killed for being angry. And then when I read that book, it was like opening one of those doors. I could easily see how something so powerful could be made into something so useful and beautiful."

Those stories laid the groundwork for Chapman’s acceptance of the library’s Noah Webster Award later in the evening. After moving to New Haven from Ridgefield, Conn. 15 years ago, Chapman threw herself into volunteering for the library and the NHFPL Foundation. She became a familiar face at Mardi Gras celebrations, aldermanic hearings, and meetings of the Historic Wooster Square Association, Downtown Wooster Square Community Management Team, New Haven Cultural Affairs Commission and others.

At the library, she began her service under the late James C. Welbourne, then continued under former City Librarian Martha Brogan and current City Librarian John Jessen. For the past four years, she has overseen the campaign for “Stetson 2.0,” a $2 million initiative to fund the Stetson Branch Library as it moves from Dixwell Plaza to the renovated Q House across the street. The branch is expected to open there this summer, with a new, 23,000-book collection dedicated to the African diaspora.

“The community is ecstatic about the new library coming,” said Stetson Branch Manager Diane Brown. “It’s been a long time coming.”

Multiple times throughout the evening, speakers noted that Chapman lives by her late mother’s mantra, that "volunteering is simply the rent you pay for the privilege of living on this earth." In a prerecorded message, Brogan recalled a time Chapman wrote and circulated a list of 100 different things New Haveners could do with a single library card. Friends praised her for her steadfast dedication to the people and institutions in her midst. Brown said that Chapman has helped usher in a new era for Stetson, which will include collaborations with the Hill Community Health Center and mentoring spaces for local teens.

Chapman at last year's Mardi Gras festivities. Lucy Gellman Pre-Pandemic File Photo.

Accepting the award against the familiar blue walls and bookshelves of Ives Squared, Chapman praised the library for continuing to provide resources during Covid-19 and a year of social upheaval, as the city faces a financial crisis and a reckoning with its own entrenched racism and white supremacy. In the past 11 months, branches of the NHFPL have reopened their technology centers on a limited capacity basis, continued curbside pickup and daily online programming, and lent out hundreds of WiFi hotspots. Last summer, the library also went fine-free for the first time in its history.

Chapman looked to Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden, the first woman and first Black person to hold the position. Hayden has been vocal in reminding members of the public that libraries are powerful, if threatened, engines of democracy. Chapman called the NHFPL “a visible representation of Democracy,” where all members of the public are invited and welcome to step through its doors no matter their race, creed, sexual orientation or documented status.

"Never take libraries for granted,” she said. “Never take your library for granted.”

The library tributes weren’t quite over. At the end of the night, professor and historian David Blight recalled his own love affair with the Flint Public Library, a large brick-and-chrome building that sat across the parking lot from his high school. "When it wasn't baseball season," Blight spent two hours each day in the library, reading history books or listening to Edward Murrow's recreations of historical events. It fed his love for the discipline, to which he today brings a vast body of scholarship on Frederick Douglass.

"I always thought, if we knew the world was going to end—and it's not, but if we did—we should all just gather in public libraries all over the United States, have an open bar, open stacks, and just have one grand debate about books and knowledge. Because public libraries are the places where civilization has gone to be saved."

To watch more from Tuesday, click the video above.