Dixwell | NXTHVN | Poetry | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | Black Lives Matter | Arts & Anti-racism

| Titus Kaphar's 2020 Analogous colors (foreground) and 2016 Destiny 1 installed in the exhibition. Pleading Freedom runs through Sept. 26 at NXTHVN, located at 169 Henry Street in the city's Dixwell neighborhood. |

Maybe the eyes are what stop you, closed in a wave of pain that extends through her brow and forehead. Or the space between her outstretched right hand and left arm, a gaping, child-shaped emptiness. Her hair, pushed back by a headband, becomes a halo-like crown. This is a Madonna without her Christ Child, as if he has been snatched away in the night.

The absence is palpable. We can feel that a small human is supposed to be there, breathing and growing between those arms. Her right hand, gloved in blue, softens as if under its warm weight. She is supposed to get the sweet baby smells, the nuzzle of a small, unstill body. But the body is gone, the silhouette removed. Part of her body has disappeared in the process.

Analogous colors, now known across the country as Titus Kaphar’s TIME Magazine cover honoring George Floyd, is one of the pieces in Pleading Freedom, a collaboration between artist and NXTHVN Founder Kaphar and poet and public defender Reginald Dwayne Betts. It runs at NXTHVN’s Henry Street gallery through Sept. 26.

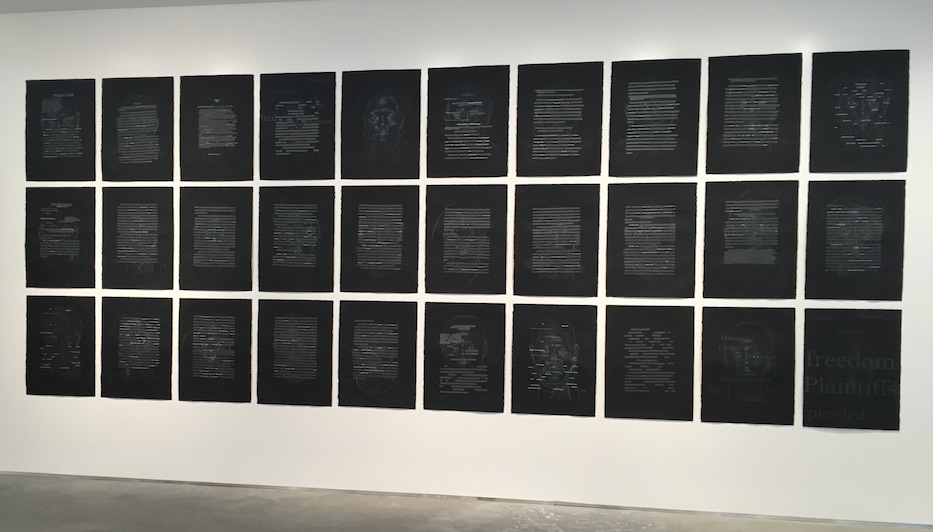

The exhibition combines Betts’ poetry, redacted legal documents, Kaphar’s artwork, and their 2019 project Redaction to weave a damning narrative about white supremacy, structural racism, and the carceral state. The title comes from the final piece in a gridded presentation of 30 partial and full redactions, in which variations on the words “pleaded,” “freedom,” and “plaintiffs” float on the paper in differently sized, silvery typeface that was designed specifically for the project.

| Detail, Analogous colors. Artwork by Titus Kaphar. |

Pleading Freedom feels at once timely and timeless, often gut-wrenchingly so. It comes at the end of a summer that has seen ongoing state-sanctioned violence, protests to defend Black lives and defund the police, and a local swell in calls for prison abolition. It follows a six-month stretch that has laid bare the parallel pandemics of COVID-19 and anti-Black racism in this country, and a six-year stretch in which the demand for body cameras has become a demand for abolishing the police. And it takes place on the lip of election season, in a country led by a man who is endorsed by, among others, a former leader of the Ku Klux Klan.

It also speaks to a deeper rot at the core of America. In Kaphar’s study for Yet another fight for remembrance, which became the TIME Magazine “Person Of The Year” cover in 2014, the artist walks a chronological line back from Analagous colors to the state-sanctioned murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, depicting the protests that followed.

Brown was an unarmed Black teenager who was shot and killed by Officer Darren Wilson, who is white, in August 2014. A grand jury later found Wilson not guilty of murder. Of the 12 jurors, nine were white. While the makeup of the jury reflected St. Louis County, where 24 percent of the population is Black, it did not reflect the makeup of Ferguson, where just over 67 percent of the population is Black. At the time of Brown's murder, 50 of the 53 officers on the force were white.

In the work, protesters fill the frame, only their eyes and foreheads visible as white paint covers their bodies. The black of their skin melts into the red of a police vehicle somewhere in the background. Their arms are raised skyward with fingers outstretched, conjuring the cry of “Hands up/Don’t shoot” as soon as they appear. For the exhaustion conveyed in the title—a knowing exhaustion that also floods Betts’ poetry—the faces are individuated and full of feeling, sets of eyes locked with the viewer and looking off to the side, beyond the canvas.

Images of the city come flooding back around them: Gov. Jay Nixon’s decision to call in the Missouri National Guard; protesters wearing bandanas, masks and sometimes helmets to shield themselves from tear gas and rubber bullets; the waves of grief that followed, and still follow. With them, there is the sense that it could be Minneapolis, or Kenosha, or Portland, or New Haven. That this fight for remembrance will happen again—is happening—because America has long normalized the spectacle of Black death.

| Installation view of Pleading Freedom. |

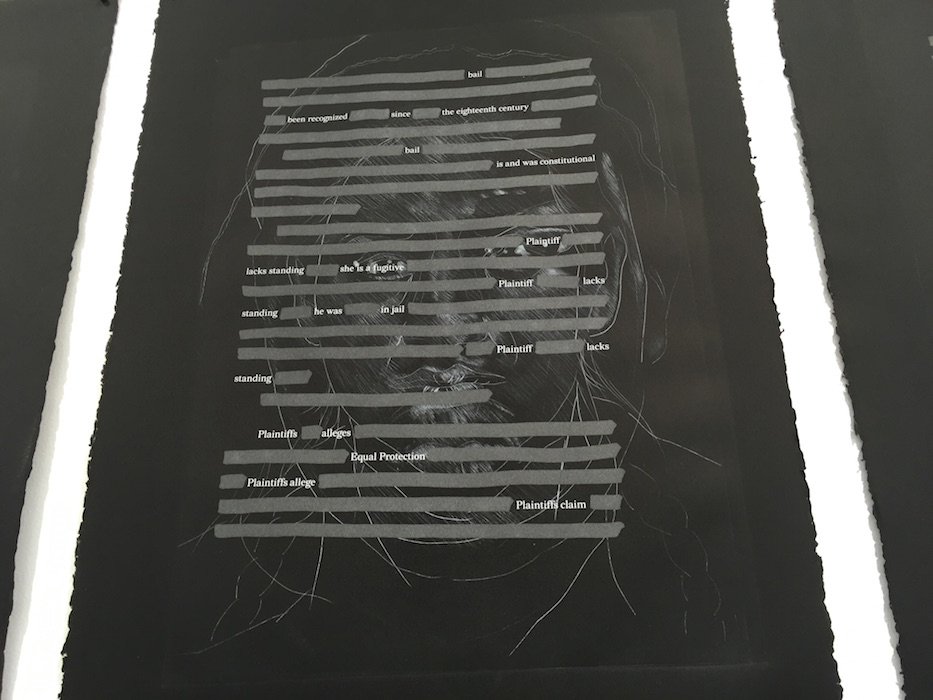

In this sense, to understand Pleading Freedom as a response to only the present would miss the point, the equivalent of a conversation on prison abolition that ultimately veers toward reform. In Redaction, Betts’ work is collapsed onto Kaphar’s etchings, rendered in a wispy white against sturdy archival black paper. The faces have a generic remove, made to look like a series of courtroom drawings. On top of them, words strain against their missing counterparts, laying bare the teeth and cruelty that are part of the system of cash bail.

The text—both present and omitted—is pulled from legal documents that the Civil Rights Corps filed on behalf of Americans who found themselves behind bars, unable to pay cash bail before trial proceedings. As Betts includes in an afterword to his 2019 collection Felon, there are some 450,000 Americans awaiting trial each night in the United States, kept behind bars because they cannot pay their way out. The work is an educational gift and damning critique, a crash course in a system that now, in the midst of a pandemic, may double as a death sentence even more than it did before.

Take Betts’ “In Missouri,” which a viewer may know as one of four redacted poems from Felon. Standing before the piece, a viewer is compelled to read through empty space—to acknowledge the absences and find the meaning between and around them.

The Plaintiffs people jailed by

the City

the City kept a human

in its jail the person

pleaded poverty

held indefinitely

threatened abused

left to languish frightened

family members could buy their freedom

| Titus Kaphar and Reginald Dwayne Betts' Redaction installed at NXTHVN. The exhibition also includes a portfolio that sits at the front of the show, just to the left of the entrance. As NXTHVN writes for the show, it "houses works on archival paper, adhered to metal 'pages,' bound in blackened bronze book, and is displayed on a walnut lectern." |

Under the words, a man’s face floats as if it is in motion. Viewers realize that it's a composite of many faces: there are at least two noses, two sets of ears, a suggestion of lips where the forehead may be. Beyond his head there’s another arc that looks like it could be a second head, or maybe the brim of a cap.

It echoes a portrait across the room from Kaphar’s 2016 Destiny series. In the piece, also a composite, a woman’s face is rendered in muted color against a uniform shock of blue. She looks young and tired; a messy bun rests on top of her head. But something is jumbled, as if she exhausted by the sheer amount of stories she holds, and the way the deck is stacked against her every time.

Across 30 interlocking redactions, viewers take in these stories, so many of which have been muted by the criminal justice system. In the most literal sense, there is the erasure of words, sentences, and the sections of faces they block out in their wake. Sometimes a strikethrough lands right in an eye, as if the face is suddenly blinded. Other times it falls close to a mouth, making speech no longer an option.

But between the lines, there is also the erasure of human lives. Not just of those who live behind bars awaiting bail or serving disproportionate sentences for their perceived crime, but also those in their orbit, who continue to survive their loss outside prison walls. The text makes clear how one decision in the criminal justice system ripples out to a whole community. In another page from “In Missouri,” a woman’s face looks out from behind bars of omitted text, eyes wide and terrified.

| An excerpt from Betts' "In Houston," one of four redactions featured in Felon. |

the treatment

reveals systemic illegality

The City has

a

Dickensian system that violates the

most vulnerable

The City of Ferguson

So much of the text has been removed that it is impossible to see her fully. After the words “The City of Ferguson,” five full lines of legal text have been redacted before exposing the words “the/City’s conduct is unlawful/It/has been the policy/To jail/people.” It seems to talk to not just the pieces around it, but to many of the pieces across the gallery.

That dialogue is where the exhibition is its strongest. Something happens when Betts, whose gift is the economy of language, is given a face behind his words, inked in the same shade as the text that is left behind. In their sparseness, the words and images communicate a succinct and deliberate kind of cruelty that is unique to this country, and the constitution on which it was built.

Within the white-walled gallery, there’s also a constant push-and-pull that makes the show as effective as it is affecting. Kaphar’s pieces radiate feeling, with currents of grief, exhaustion and indignation that roll clear off the canvas. Across from them, the works from Redaction are deliberately impersonal and constrained, making their point through the process of erasure. Kaphar’s 2019 State Number Two (Dwayne Betts) sits on a wall at the back of the space, a sort of bridge between the two.

| Titus Kaphar, State Number Two (Dwayne Betts), tar and oil on canvas. |

The work is a beatific portrait of Betts on a gold background, dipped in thick, black layers of tar that have been sprinkled with gold leaf. The tar extends to Betts’ upper lip; it rises from the canvas, almost wave-like. Suddenly this man, whose currency is words, is unable to speak. His eyes burn. They are exhausted and fiery as they lock eyes with the viewer, as if to communicate what his voice no longer can.

The portrait follows the same process Kaphar used in The Jerome Project, during which he painted a series of men who carried the same name as his father, all affected by incarceration and the prison industrial complex, and dipped them in tar. To the right of the work, Betts' poems “After Prison” and “For A Bail Denied” sit side by side. The text is so hard to see against a black background that the viewer must get close to the works to read them.

Both poems come from Felon; it feels intimate to get this close to them. In the former, a ghazal that opens the collection, Betts chronicles some of his own journey through reentry, including the making of State Number Two that now hangs beside it. In the latter, he recounts the story of a boy in a courtroom, still young, as the system fails him. The poem ends with the shattering lines "& we was too powerless to stop it/& too damn tired to be beautiful."

In this exhibition without labels, the works double as a narrative guide and stark reminder of what is at stake in a system that penalizes people for their Blackness and their poverty. In his own words—which are well worth reading beyond four walls on Henry Street—Betts echoes a question Kaphar has posed in his own work, in both the title and accompanying poem for Analogous colors.

Are black and loss/analogous colors in America?

Pleading Freedom runs through Sept. 26. NXTHVN is located at 169 Henry St. in New Haven's Dixwell neighborhood. The gallery is open Thursday through Sunday,