Black History Month | Books | Arts & Culture | New Haven Museum | COVID-19

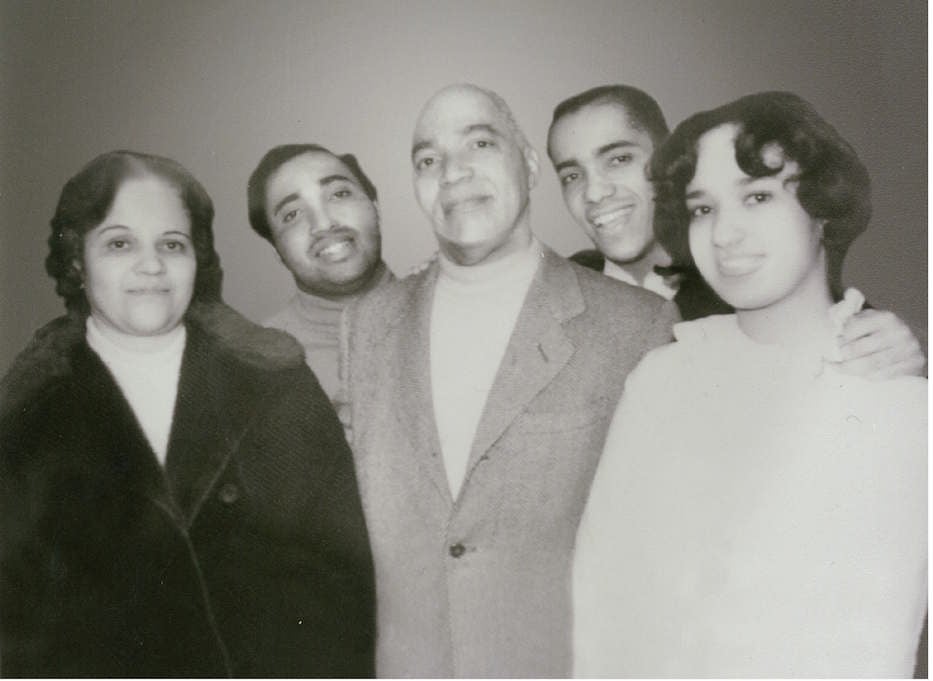

The Snyder family in 1969. Photos courtesy of Jill Marie Snyder.

Luther is writing Mary on the beach, as he watches people walk up and down the boardwalk. He’s read her letter 17 times since getting it. A reader can almost see a split screen of the two: Mary giggling as she reads the words, Luther’s pen scratching the paper, a few flecks of sand on the page. It’s the beginning of a great love story with New Haven and the city’s rich Black history at its core.

Author Jill Marie Snyder brought that history to the New Haven Museum Wednesday night, in an hour-long talk on her new book Dear Mary, Dear Luther: A Courtship in Letters. The book followed her mother’s death in 2007, after which she transcribed the letters, compiled family history, and immersed herself in genealogical research. She will return to the museum for a virtual family history workshop later this spring.

“It really forced me to think about them, and to think about each of them—their impact on my life,” she said Wednesday, joining the audience via Zoom. “And I evolved to thinking about them much more broadly than just being my mom and dad. I really started to think about them more wholly.”

Snyder’s story begins long before 2007. Her father’s family hailed from Deep Creek Valley, Penn., a former stop on the Underground Railroad that is today called Pottsville. Her father’s grandfather, Simon Snyder II, was a chef who spoke Italian and German. He grew up next door to the woman who ultimately became his wife, Snyder’s paternal great-grandmother Charlotte. The two had a daughter named Maude. At some point, she migrated to Wilkes-Barre, Penn., a town in Pennsylvania’s coal country where the population hovers just over 40,000 today.

Maude’s son, Luther, was born there. While Maude raised him by herself, Luther’s seven uncles became his “father figures,” Snyder said Wednesday. Together, they “made sure that Maude and my father were well taken care of, and had everything they could want.” Meanwhile, it was his mother’s only sister Delphine who played a role in bringing Mary and Luther together.

Delphine lived next door to Mary Brooks, one of two daughters to Stella and Clarence Brooks. Stella and Clarence had started their lives in nearby Catawissa, where just over 1,500 people live today. Stella was white; Clarence was Black. After eloping in 1917, the two first moved to Bloomsberg, Penn., which Snyder described as “in that red part of Pennsylvania that you see on the map on election night.”

It was hard for them. Stella’s brothers disapproved of the marriage. The two ultimately left town due to the threat of racism and physical violence, including some that Stella believed came from her family. It cost them family connections, then Clarence’s barbershop, then their privacy and almost their lives.

“My mother recalled families, sometimes people marching in front of their house,” Snyder said Wednesday. “I won’t name any particular group, but sometimes burning crosses on the lawn. And eventually, they burned down the barbershop. And at that point, that’s when my family moved … I think they realized that the next stop would be attacking them personally and that they had to go.”

They didn’t know it then, but that move to Wilkes-Barre was the beginning of another great love story. In 1935, Mary and Luther were paired in a wedding procession while she was still a junior in high school and he was in his twenties. Luther "was smitten” with Mary from that first encounter, Snyder recalled. He discovered that she lived next door to his aunt Delphine, to whom his visits had been few and far between.

Suddenly, he visited her frequently, and spent “hours on the Brooks’ porch” next door after checking in on his aunt. For a year, he spent time with both Mary and her sister, Sarah. Then he made his move.

By 1937, Mary was finishing high school. Luther traveled to Asbury Park, New Jersey, hoping to find work at a summer resort. The two began writing letters to each other, the hesitancy and then warmth of their words radiating through the pages.

The letters tell the story of two people falling in love, in that timid and enticing dance that’s still timeless if people do it right. Snyder joked that she found a certain stiffness—“they’re very polite, how are you, blah, blah, blah”—in the first few. Then in June of 1937, something cracked open. Luther wrote a record of his days, in which he would sit on the beach “watching the waves roll in and out on shore.” A reader can almost imagine him reclining in the sand or in a hotel room, combing back over the details of his day to make sure nothing was left out.

“I put my dark glasses on and stroll up and down the boardwalk,” he wrote after noting that he’d read her letter 17 times. “Everyone wears dark glasses therefore everyone looks alike—white and colored.”

At the end of that summer, Luther relocated to Harlem. The city was an explosion of creativity that he had never experienced before: he saw Ella Fitzgerald and Wesley Bunch perform. He went dancing and found a job at a hotel that was enough to pay the bills. In Harlem at the height of his bachelorhood, he never stopped writing sweetly back to the hometown girl who lived next door to his aunt.

“He’s being kinda cute,” Snyder said after reading a letter that referred to Mary as his favorite. “I think he’s learning to be a playboy myself.”

Mary visited the city in 1938, and left worrying that Luther (or as he wrote to her, Luke) had become too enthralled with the big city to want a girl from small-town Pennsylvania. Luther wrote back and insisted she was always the one for him. For a year, Snyder said, they played a gentle, flirtatious tug-of-war.

Then on New Year’s Day in 1939, Luther wrote seven pages on hotel stationery, telling Mary that “everyday is a holiday since I met you” and “you really do things to me.” It was a turning point in the relationship. As she read, Snyder displayed one page from that day, in her father’s wild, inky black scrawl.

While noting that “I think my dad’s a little bit tipsy,” she focused on the sheer outpouring of emotion in the letters. Initially, she said, she’d been surprised by it—her father often kept his cards close to his chest. The words did their job: Mary and Luther kept corresponding. After two years of visiting each other, they married in Harlem in January 1941, on Luther’s 30th birthday.

“At one time I scoffed at the word love and the idea of marriage,” Luther wrote the fall before their marriage. “Then at the first sight of you, I began to feel somewhat of a change in my outlook of life only I was a little timid in admitting it. And now I can’t conceive anything but planning my life for you and with you.”

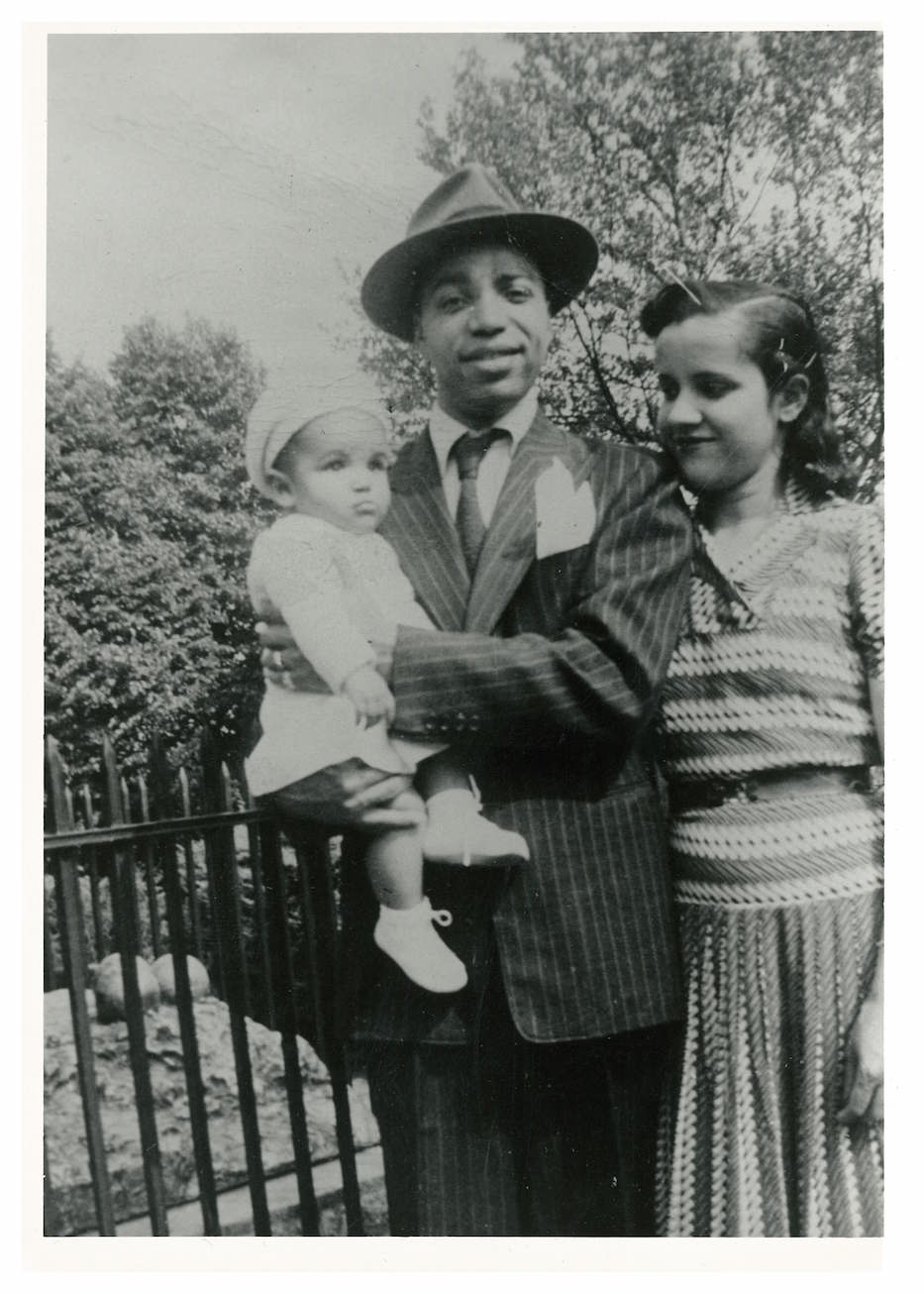

Luther and Mary with Snyder's brother, Roy. Photos courtesy of Jill Marie Snyder.

Six months after the two married, they moved to New Haven with the promise of work at the Winchester Repeating Arms Company. As she spoke, Snyder pulled up a postcard of Chapel Street, a bright array of squat buildings set against a blue sky. Wisps of cloud floated in the background. She noted that the city “was a boom town” during that time, thanks in part to World War II.

“There were tons and tons of jobs,” she said. “Everybody was able to find work.”

Her father began work at Winchester Arms; everyone in her family later crossed paths with employment at Yale. As more Black people arrived from the American South, she said, her parents faced housing shortages and discrimination. After visiting New Haven on her own, her mother’s white mother moved the entire extended family to the city. Snyder and her two brothers were born in the city, at a time when the maternity wards in Yale New Haven Hospital were still segregated. White mothers got beds and hospital rooms. Black mothers got cots in the hallway.

Learning her family’s history encouraged her to delve deeper into the city’s, she said. As she thought of how racism had dashed some of her parents’ dreams—life as an artist for her mother, college for her father—she found the names of slaveholders who had lived in New Haven in the 18th century. She recognized some of the names from the streets she lived and walked on, including Esther Mansfield, John Nicoll, Richard Woodward, Hezekiah Hotchkiss and James and Mary Hillhouse.

She discovered Elizabeth Tritton, a slaveholder who was responsible for the final sale of a Black mother and daughter on the New Haven Green in 1825. The daughter, named Lucy Tritton, became one of the founding members of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church.

She also found that it wasn’t factory labor that first attracted Black people to New Haven: the city was a place where free and enslaved Black people lived at the same time in the 19th century. By the 1830s, that divide had created what author Robert Warner calls a “caste system,” in which free Black people could only live in Fair Haven (then known as Little Liberia), the Hill neighborhood, and a so-called “Poverty Square” in what is now Dixwell.

Those years also saw great resilience, she said. She looked into the creation of the Dixwell Congregational United Church of Christ, which celebrated its 200th birthday last year. She dug into Varick AME Zion Church’s 1818 founding, which meant that the church was nearly 100 years old by the time Booker T. Washington spoke there in 1915. She did research into St. Luke’s, where she spent time as a child.

She still wants to learn more about oft-overlooked Black people in the city that she called “the strivers" Wednesday night. They include the Rev. Jacob Osun, engineer William Lanson, military hero Peter Vogelsang, self-emancipated slave William Grimes, and others. She is fascinated by the Rev. James T. Holley, who founded the Haitian Episcopal Church, and educator Ebenezer Bassett, who was appointed ambassador to Haiti in 1869. She also wants to learn more about Sarah Boone, the forgotten Black woman who is responsible for the ironing board.

“I really feel it’s important for everyone to tell their family story, but especially I want to encourage African-Americans to tell family stories,” she said. “One reason I feel it’s important is that reverence for ancestors is an important part of African culture. And by focusing on our family stories, learning more about our families, we—I’ve found a deep sense of joy and gratitude for all that my ancestors did for me.”

Snyder also reflected on the racism she has continued to experience in her own life, over a century after her grandparents both found their way to Wilkes-Barre. She remembered going to a friend’s house at the age of six, and getting the door slammed on her little face. Snyder walked home by herself. She burst into tears when she got home.

Her mother "sat me down on the couch" and broke down white supremacy. She told her that some people would dislike her—not for any fair disagreement, but “because you’re a little colored girl.” Decades later, it informs Snyder's work with the Community Healing Network, Inc., which seeks to break through the myths that have enabled and maintained anti-Blackness in this country.

She also recalled a much more recent run-in with structural racism on a Vermont highway. It was a weekend afternoon, and the highway was clogged with traffic. Snyder was going within the speed limit; everyone was. A state trooper pulled her over, sirens flashing, and asked if she was American. She knew, in an instant, that he felt entitled to do so because she was a person of color. She was enraged.

“Racism is a fact of life for every Black person, and every child has that moment, when you realize that being Black is going to make you stand out, is going to create barriers, and there are people who are not going to like you,” she said. “It’s just a fact of life. In my family, the mantra was, you just have to work twice as hard to get half as far as other people.”

“It’s not so much that racism is something that you have moments of bigoted interactions,” she later added. “It’s the general economic and social lack of opportunities that is really what is most damaging.”

Dear Mary, Dear Luther: A Courtship in Letters is available online. Snyder will be presenting a workshop on family genealogy at the New Haven Museum in March. Details to be announced.