Arts & Culture | Westville | Studio Visits

| “That’s where the conversation in my head is now. This question of, what can I do with my art?” Lucy Gellman Photos; all art by Molly Gambardella. |

There’s no one place to look when you step into Molly Gambardella’s studio. From the ceiling, a book’s innermost secrets have been reworked into a functional chandelier. Soft, huge lichens burst from the white walls, smaller ones winking out like bright stars. Sleek wire sculptures meet riotous, other-worldly canvases. In one, a spaceship shape takes off, neon blue as it leaves the ground and goes on to another universe.

This Narnia has become commonplace for Gambardella, a longtime New Havener who has been bridging art, eco-activism and social justice with a series of huge, bright lichens, sharp and witty pencil sculptures, and border-defying paintings. Now situated at West River Arts, she is preparing for a fall that includes City-Wide Open Studios, window installations in downtown New Haven, and her inaugural trip to the American arm of the Art Basel festival in Miami Beach, Florida.

“I like to tackle way too many things at the same time,” she said on a recent visit to her studio, which overlooks the cacophony of Whalley Avenue. “So that is how this happens.”

Gambardella’s interest in the arts began in New Haven during her childhood, as a student at Neighborhood Music School and Creative Arts Workshop. While she was born and raised in nearby North Haven, “I essentially grew up on Audubon Street,” with training in African drumming and dance, video, visual arts, and later trombone, which her dad also plays.

She was, by her own admission, a pensive child: by the time she was 12, “I was like, ‘what am I doing with my life?’” she recalled. “It was evident to me that I wasn’t going to be Mia Hamm.”

Instead, she enrolled in the Educational Center for the Arts (ECA), where her older brother was also a student. During the first half of the day, high school was a slog through the North Haven school district. But in the afternoons on Audubon Street, “It was magic.”

At ECA, Gambardella “had no idea what I liked,” but gravitated slowly towards sculpture. She credited one teacher in particular, sculptor Johanna “Hanni” Bresnick, for endearing her to the medium: she often called Gambardella up for demos, and taught her how to use equipment. Gambardella recalled being the only female student in the class, and watching transfixed as Bresnick showed students how to use power tools, then asked Gambardella to try them out.

“Just seeing a woman sculptor was huge,” Gambardella recalled. “She was so supportive of me.”

In turn, the young artist carved out a niche for herself: methodical large scale installations and big sculptures with lots of moving parts. Sometimes, it was a whole room designed entirely out of string. Others, she stitched all of her dad’s ties together, and then kept going. Her junior year, she went to liquor stores to find discarded beer cans that were “still sticky and smelly” and turned them into a living installation, with which student dancers could interact. It didn't bother her that the owners, often happy to get rid of old cans, raised their eyebrows at a teenager who just wanted the sticky aftermath of booze.

“I just knew I was a 3D person,” she said, recalling a summer spent with Brooklyn-based sculptor Carolyn Salas in Artspace’s Summer Apprenticeship Program. “When you’re doing that work, you don’t have to think about anything else. I learned that I couldn’t expect perfection when I was making experimental things—that it was an exploration.”

By her senior year, teachers were encouraging her to attend art school for a BFA degree. She applied to all “these big art schools” with a plan to attend the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). When she didn’t get into her first choice program, something snapped in her head.

“I was 17 years old and I didn’t know where I was headed,” she said. “You're dealing with all these expectations.”

It was the beginning of Occupy Wall Street in New Haven, the spring of 2012. Gambardella left home, pitched camp on the New Haven Green, and joined a movement to fight economic inequality.

At the time, she said, she had no real sense of how transformative the Occupy movement would be for her life and for her career. On the Green, she saw “this huge divide between wealth and poverty” that changed the way she saw the world around her. Instead of thinking about college—her high school graduation was just around the corner, and she was scheduled to give a senior speech in North Haven—she thought about big banks and the 99 percent. She started protesting and used her skills to make signs over sculptures.

“At the time, I wasn’t considering myself an artist,” she said. “I just made stuff.”

After police forcibly cleared the site in mid April, she moved into the now-defunct Atwater Resources Cooperative in Fair Haven, then on to a national convening of Occupy protesters in Philadelphia. By then, she had missed almost three months of school. It was a thrill for her: she met political performance artist and provocateur Vermin Supreme, who set up a platform for her to give her senior speech on site. She made friends with protesters, with whom she was arrested and later moved into an abandoned warehouse, turning rooms filled with garbage into shared studio spaces.

It was there, she said, that she started to reconnect with art making. During the day, she volunteered at Wooden Shoe Books & Records, an anarchist bookshop in South Philadelphia. At night or in her off hours, she worked on turning a bathroom into an art studio, a process that involved removing used needles and garbage, cleaning the room, and putting in shared supplies that people could use.

“This is kind of when I knew art was important,” she said. After close to a year of living in Philadelphia, she moved back to Connecticut, into a garage close to the Paier College of Art. In 2013, she started as a student in the school’s illustration program, still unsure she was in the right place. When she wasn’t in classes, she was dumpster diving and serving food in the Hill through the city’s chapter of Food Not Bombs, with which she had originally become involved in Philadelphia.

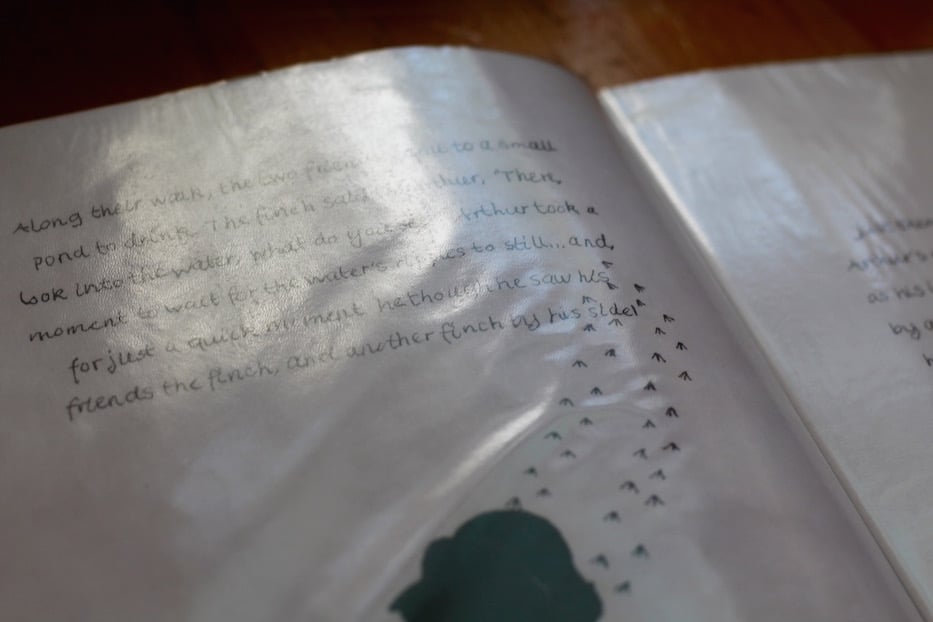

Her teachers assured her that she was where she was supposed to be; she praised multimedia artists and professors Peter Bonadies and Vladimir Shpitalnik in particular for giving her permission to experiment. And she did: in those years she wrote and illustrated a book that she still keeps in her studio. She tried her hand at welding and tamed sinuous wire, working it into sculptures that she still keeps on her walls. She started a temp job for the Yale School of Drama, organizing their props warehouse on Hamilton Street.

She also realized that she was hearing the same few female artists mentioned over and over again—and began to educate herself when art history books weren’t cutting it. It was her entry into Louise Bourgeois, Ruth Asawa, Yayoi Kusama. They became her role models.

“As an art student, you’re like, why am I only learning about Frida Khalo and Georgia O'Keeffe?” she said. “How many more dissertations in Picasso and Dalí do you need?”

When Gambardella graduated in 2017, “I kept thinking that I would not be able to make it as an artist.” But she did, first cobbling together work in substitute teaching at ECA and her job at Yale, which ran through 2018. She landed at West River Arts, a studio move that she said “put me on a good path.” And she started traveling to drop off commissions—to the U.S. and Canada, and then to cities that were sometimes halfway around the world.

After a recent visit to Mexico City, she started in on her work “La Gran Ocultadora,” a border-busting abstraction that now hangs in Sanctuary Cities and the Politics of the American Dream.

It was during that time that the artist also started working on the projects for which she may be best known around New Haven: her huge, vibrant sunburst lichens, inspired by her time in the White Mountains of New Hampshire and a “greenhouse” full of fake foliage she organized during her time at the props warehouse.

When she started in on the first one, Gambardella said, she had no idea what they would become in her work. The sculpture was an experiment: she worked fabric petals into half a plastic bubble, and built the petals onto each other, so the structure supported itself as it grew outward. It was an undertaking that felt meditative, huge, and beautiful—and mirrored a resilient and endangered part of the natural world that she loved.

“It was therapeutic,” she said. “To be able to do that was like, ‘I’m doing one petal at a time.’”

On a visit to her studio, a young kid took to the first one immediately, and his family bought it on the spot. As she created more of them—the Chicago arm of the co-working space Convene commissioned one last year, as have several new commissions she can’t yet name—their symbolism and meaning deepened.

She recalled working on one last year, after falling off a ladder and breaking her arm in Vermont. Because the commission couldn’t wait, she’d gone ahead, doing the work with one hand as she stored petals in the open space of her sling.

“They’re about the environment, perseverance, mental illness, positivity, and appreciating life’s nature,” she said. “You hear about our planet, and how it’s dying, and it can be debilitating overwhelming when you feel like you can’t do anything about it. My intention is to push out as much joy as possible, but while not ignoring everything that’s happening in the world.”

In fact, she’s been directly interacting with everything that’s happening, turning towards eco-activism, immigration, and even the #MeToo movement in her current work, while passing that knowledge on as a new adjunct professor at Paier this year (she will also share it in Miami Beach, where she is heading with a Westville contingent of artists for Art Basel this December).

Inspired by fellow West River artist Howard El-Yasin, she has been looking at how to integrate more reused and sustainable materials into her work, while building a bigger public art component. Through her commissioned lichens, she’s been spreading that message slowly across New Haven, and parts of the country. She said she’s interested in adding new fungi to the mix, inspired partly by her travels to Glacier National Park and time spent outside locally.

“That’s where the conversation in my head is now,” she said. “This question of, what can I do with my art?”

A look around her studio reveals that vision in the making: her signature colored pencil sculptures meet a whole wall of lichens in an array of tones and sizes, so bright it’s as if they are bursting straight from the paint and plaster. Across from snugly packed bookshelves, tiny dinosaurs seem to take root in potted plants that sit by her windows, greeting the daylight with their huge primordial jaws. Until recently, she and artist Martha Savage raised snails in the space. Now, she’s buzzing away on a book based on her exhibition of mail art earlier this year. Everything points back to a closer look at the world around her.

“Lichens only survive where the environment is good,” she added. “I think that’s such a beautiful metaphor. Like, how can I be the lichen here?”

Molly Gambardella's studio will be open Oct. 12-13 for Westville Weekend of City-Wide Open Studios and is usually open during Westville's 'Second Saturdays" series on the second Saturday of each month. For more on the artist, visit her website.