Economic Development | Arts & Culture | Music Haven | State Legislature | COVID-19 | Arts & Anti-racism

Clockwise, from top: Music Haven dad Robert Nunez, who has two kids in the program and testified Friday; Executive Director Mandi Jackson; violinist and senior resident musician Gregory Tompkins; and parent, board member and development associate Lygia Davenport. Screenshots from YouTube.

Supporters of a local music nonprofit came to the legislature to save its state funding for the second time in two years. Four hours later, they had outlined a vision for the arts that includes mutual aid, housing security, and basic protections for some of Connecticut’s most vulnerable workers.

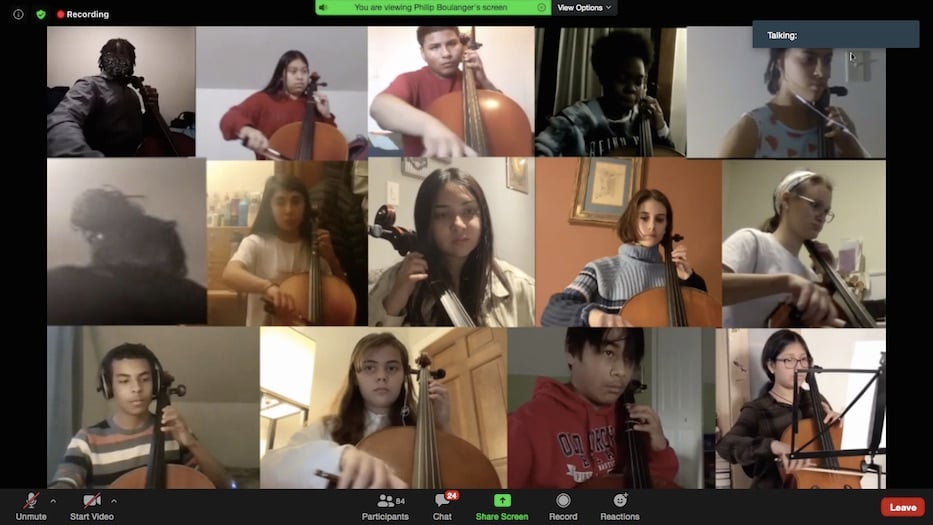

That nonprofit is Music Haven, which has continued to teach over 80 students from chronically underfunded, under-resourced, and historically redlined neighborhoods via Zoom, Google Meet, and FaceTime during the Covid-19 pandemic. Friday night, dozens of teachers, students, parents, and supporters testified in support of the organization before the state legislature's Appropriations Committee. By the following Monday, over 80 testimonials had been submitted, all of them in support.

Champions of the New Haven nonprofit also threw their support behind proposed protections for domestic workers, in a show of working-class solidarity that is rare if not unheard of for the state’s arts organizations.

The push came after Executive Director Mandi Jackson read a copy of Gov. Ned Lamont’s recommended biennial budget two weeks ago, and discovered that Music Haven’s direct line item had gone from $100,000 to $0 without warning. Last year, Jackson and a small army of Music Haven supporters testified at the State Capitol in an attempt to save the funding. At the time, legislators said that the omission was an error. New Haven State Rep. Toni Walker, who chairs the appropriations committee, did not reply to multiple requests for comment for this story.

“We were assured our funding would be restored, and then it didn’t happen,” Jackson said Friday, testifying against a Zoom background teeming with young musicians. “I found out a week ago that we weren’t in the budget. I thought that we were. I found out a week ago that we weren’t, and it was a pretty devastating blow considering what’s been going on this past year.”

Reign Bowman in October 2019. Lucy Gellman Pre-Pandemic File Photo.

In four hours of testimony, staff, families, and supporters of the organization laid out a vision for music education that pointed to the arts as a human right, rather than a luxury. Reign Bowman, a junior at New Haven Academy, noted via written testimony that she “would have no way to express myself the same way as I am able to express myself with my violin.”

During the past 11 months, her instrument has become a source of comfort and consistency as school remains online and the Covid-19 pandemic approaches a full year. Each week, she works with violinist and resident musician Gregory Tompkins to hone her skills, from new sheet music to a vibrato that has broken out of its shell. In October of last year, she performed alongside Tompkins in the Haven String Quartet’s first virtual concert since the start of the pandemic.

“I am asking as one of the Music Haven students that you can please fix your mistake and not forget about us because Music Haven means so much to me,” she wrote in a testimony that Tompkins read aloud Friday. “Please consider fixing the mistake and providing the funding back to Music Haven.”

Others called the funding an issue of long overdue arts equity. Currently, the bulk of line item funding goes toward institutions that can make an argument for the statewide economic impact of their work. Direct line item funding is responsible for 70 percent of the state’s arts funding; the remaining 30 percent comes through grants distributed by the Connecticut Office of the Arts.

The formula, which comes out of the Department of Community and Economic Development, puts organizations that offer arts education at low or no cost at an inherent disadvantage. They do not collect high tuition or ticket revenue, employ hundreds of contract workers, or bring in tens of thousands of tourism dollars per year. Often, they do not collect any revenue at all.

Music Haven students at their winter 2020 performance party, which was held on Zoom.

In Music Haven’s case, 91 percent of students identify as non-white, and 82 percent come from families living below the Federal Poverty Level. For 40 percent of students, including new immigrants and refugees who have resettled in New Haven, English is not the primary language spoken at home. When Covid-19 hit New Haven last March, the nonprofit shut down its Fair Haven offices and made the virtual leap within a week. In addition to lessons, it has provided direct financial assistance, worked to bridge the digital divide, and checked in on both students and families on a weekly basis.

Lygia Davenport, a Music Haven parent and board member who has three young musicians at home, recalled testifying a year ago at the State Capitol in Hartford. Last February, she was still teaching in the New Haven Public Schools. There were only whispers of a global pandemic. So in mid February, she drove up to Hartford in a carpool and waited four hours to testify on behalf of the organization.

A year later, she is a part-time development associate at Music Haven, a professional jump that she was forced to make “because of the pandemic and having a medically fragile child at home,” she said Friday. In her current position, she sees a tension between what the organization has and what it needs. For the past 11 months, donors have written to say they cannot give at pre-pandemic levels. Fewer new donors are coming in. Meanwhile, need has skyrocketed among Music Haven families.

As she spoke Friday, she pointed to the organization’s commitment to its students, from a 100 percent college matriculation rate and college preparation programs to additional support to families who “have lost income, homes, and even immediate relatives and all while grappling with these challenges amidst the pandemic.”

“Music Haven Has been the place that they felt most comfortable sharing their struggles,” she said. “I believe this is due to the long-standing commitment and relationships built within the program. As I have stated in the past, Music Haven is not just free lessons, it is so much more than that. It is consistency, reliability, and a symbol of hope.”

Luz and Pedro Villanueva, who are raising a child with autism and multiple learning disabilities, praised the organization as transformative for both their daughter’s musical ability and her social and emotional development. In advance of Friday’s hearing, the two submitted testimony outlining what it has meant to watch her grow under Tompkins’ careful mentorship, which has continued in virtual space.

“A ‘simple’ task like positioning her finger on the instrument or public speaking seems like an easy activity, but when you have challenges to coordinate between your brain and your muscles make these ‘simple’ tasks a whole new level of difficult,” they wrote. “Please we invite you to reconsider defunding Music Haven and please look behind and beyond the numbers.”

"All Of These Things Are Connected"

Music Haven Executive Director Mandi Jackson in Hartford last February. Lucy Gellman Pre-Pandemic File Photo.

Many of those who had come to support Music Haven extended their support to domestic workers, who asked Friday for the creation of a new line item and labor laws to financially protect them during the Covid-19 pandemic. There is currently no such line item in Lamont's proposed budget.

Speaking in Spanish and English, nannies, house cleaners, drivers, and personal assistants testified in support of the line item, which would come through the Department of Labor. Their voices sometimes trembled as they recalled sudden pandemic-era layoffs with no economic safety net in place. A chorus of voices from Music Haven joined in to back them.

“Many of the families of my students at Music Haven rely on wages from domestic work,” Tomkins said. “This money would be important in normal times, but to support them with this money in our current world … it’s not really possible to overstate how essential it is.

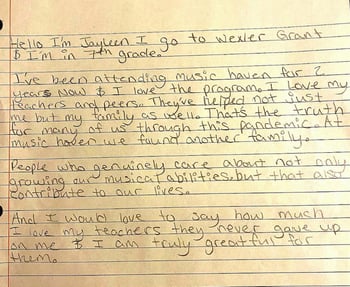

Testifying close to the end of the night, Jackson agreed. She urged legislators to refer to her written testimony for a breakdown of the organization’s work, then pivoted to a letter she’d received from violinist Jayleen Hartman. A seventh grader at Wexler Grant, Hartman has been in Music Haven for two years. Friday, she submitted a handwritten letter explaining that the nonprofit has become an extension of her family.

“All of these things are connected,” Jackson said, turning her attention to the proposed line item for domestic workers. “So many of our children at Music Haven have parents, family members who are domestic workers, and it impacts every single part of their life and their development and their ability to participate in our program as musicians if they have their wages stolen, if they break their bodies doing the work, and they have no recourse.”

“We’re tired,” she said. “You’re all tired. We’re tired of fighting this every single year.”