Creative Arts Workshop | Photography | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | COVID-19

| Luciana McClure Photo. |

It was a small group—maybe nine or ten. Some were artists, and others had never held a brush. Most had watched life sculpt creases into their faces. They sat together in deep thought.

The presenter asked one question of them all: “How would you document your quarantine?”

On Thursday afternoon, artist and activist Luciana McClure held an online seminar titled “A Day in Your Life: Documenting 24 Hours During a Pandemic.” A photographer and co-founder of Nasty Women Connecticut, McClure hosted her seminar in conjunction with Creative Arts Workshop, a community art school and art gallery that usually runs out of its Audubon Street building.

In response to COVID-19, the organization has moved all viewings and classes online. According to CAW, McClure’s session joined one of over 900 held on its virtual platform.

Rather than an instructional session, the seminar was a free-form discussion on documentation. McClure introduced several artists’ pieces to demonstrate exemplary work. Participants viewed photographer Chris Randall’s New Haven Porch-ritz series, NPR intern Kisha Ravi’s "Documenting Self-Isolation: 14 Days Through 14 Instant Photos," and a joint work by photographers Kasia Strek and Pete Kiehart titled Coronavirus in Recovery.

.jpg)

| Valerie Rogotzke and Jessy Griz. Chris Randall Photo. |

McClure challenged attendees to utilize photography just as the artists had done. She described photography as a medium to showcase their quarantine experiences. Participants took five or more pictures throughout the day of what they saw fit.

“When we think about the way things have been documented in the past, we think about an image,” she said. “We’ve seen over hundreds of years how humans have utilized the tool that is image-making. Now, we have phones to make things a little easier. We need to find a way of creating some sort of documentation of how we’re all living at this time, particularly because this is not only happening in our community but throughout the country and throughout the world.

“This is an opportunity to understand how others are handling this situation, how other people have chosen to document their day-to-day experience,” she added.

Participants analyzed four of these experiences—McClure’s work and three attendees’ own.

A Family Quarantined: Luciana McClure

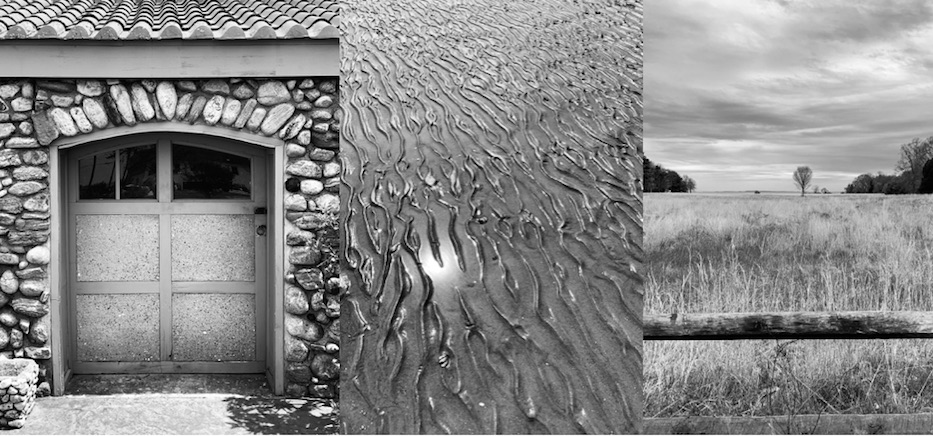

| Luciana McClure Photo. |

McClure goes by many names. She wears the sobriquet “Lucy” for her friends and peers. Acquaintances call her by her given name, Luciana—one that her classmates were hesitant to pronounce when she arrived from Brazil with her family several years ago. But her most cherished moniker, she told the class, is “mom.”

McClure’s family is the most important thing in her life. It has shaped her quarantine experience, and by extension, her 24-hour documentation process. The photoset was in black and white, a gallery of intimate moments with her children and partner.

At one point in her presentation, McClure posted a picture of her young son. It was the first time she had made him wear a mask outdoors.

“I wake up in the middle of the night with insomnia or worried,” McClure told the group. “How do I handle having small children in this pandemic? It’s made me a little more sensitive to everything. How do I protect them, but at the same time, make them aware of what’s happening without freaking them out?”

The artist wrestled with that sentiment throughout her showcase. Some pictures displayed her son and daughter playing with each other in the woods or by bodies of water. One showed her partner cutting his hair in their bathroom mirror. In another, family members cuddled with one another under a heap of blankets.

| Luciana McClure Photo. |

Despite the warmth and light those photos connoted, COVID’s tendrils bled at the edges of her work. Pictures exhibited closed parks and recreational centers. There was a swathe of shadowed self-portraits done through Zoom—screen fatigue. Photos held windows shot in the dead of night—McClure’s form of escapism in isolation. By the end of her presentation, viewers left with a distinct melancholy.

“Whether I’m going to share it or not, my work is definitely very personal to me, because I photograph what evokes some sort of feeling inside of me,” she said. “I’m hoping that by photographing it, I can recreate that sentiment and invite others to feel the same.”

“One Covid Day:” Gaile Ramey

A single peony budded before the camera’s aperture; its flower stand read “closed” just out of frame. Photographer Gaile Ramey sat in the sand for a shot by the surf, a chihuahua by a baby carriage just past the foreground.

In response, Ramey photographed a beach’s sign that prohibited visitors.

“When people document contrasting things, it creates meaning,” she said.

A neighbor’s mailbox was the focus of one photo. It was covered in paper hearts, an act of gratitude from the community for her work as a nurse. Recently, she was told her entire floor would be COVID-positive patients.

Still, Ramey ended with a symbol of hope. It was a picture of a plant “rich and alive.” She explained that it was a breed that nurtured butterflies’ life cycles.

“It’s like a harbinger of the future that’s to come,” she said, “The beauty of the future.”

Geometric Living: Kathleen DeMeo

| Photos from some of the artist's daily walks. Kathleen DeMeo Photos. |

Kathleen DeMeo’s art centers on monotypes, a form of printmaking. For years, the New Haven artist has taken pictures on her daily walk and posted them to Facebook. Her presentation combined both of those pursuits.

Stuck inside, DeMeo projected the sense of wonder and appreciation she held for her outings onto the walls of her home. From her favorite couch, she examined the room. She saw geometric shapes everywhere she looked.

“The rectangle of the TV and the shutters and everything was kind of this geometric abstract, which is something that interests me,” said DeMeo.

| Kathleen DeMeo Photo. |

Her window cast beams of light in the shape of a spider’s web. The sky’s blue matched the azure of Alex Trebek’s “Jeopardy” program on her television screen. From her cushioned perch, a place of “comfort and familiarity,” the landscape became monotypes. Isolation became art.

“It was just a different approach, I think, to the whole thing, to have a design sense during this period of time,” DeMeo mused.

Illness in Isolation: Yael Dresdner

| Yael Dresdner documented her illness in isolation, sometimes in vignettes that showed her in her most vulnerable and intimate spaces. Yael Dresdner Photos. |

On March 18, Yael Dresdner felt a fever coming on. Three days later, she became bedridden. While she never confirmed the result with a test, the artist feared that she had the novel coronavirus.

Dresdner regularly engaged with fine art and design in her day to day as an artist. She loved to focus on the hands and feet, appendages sensitive to touch. Illness and isolation prevented her from all contact.

“I didn’t move from my bedroom for a long, long time,” she recalled.

Her photo set revealed that. There was a selfie from her bed, her pale visage reflected in a body mirror across the room. A foot dug into the creases and folds of her duvet. Later, she photographed half an avocado, proud that she’d been able to stomach it. Gone was the finesse of fine art—Dresdner’s experience was raw and real.

Her recovery carried a sense of renewed hope. She took a picture of the food in her kitchen, glad that her husband had ventured out into New York’s streets on her behalf. A vase of flowers sat by the window in another shot. The flowers were from her elderly neighbors upstairs. Dresdner’s husband had collected food for them as well.

Finally, Dresdner held a sculpture made of hand cutouts to her camera. Through Zoom, she explained that it was inspired by Tibetan prayer flags.

“Blue for space and sky, white for air, red for fire, green for water, and yellow for earth,” she said. “They are supposed to create good and send good. I cut out the hand-shapes so that when I took it outside, I could photograph the city through the holes. It’s about waving hello, and it’s a cheerful form of touch.”

Dresdner’s socially distanced greeting doubled as a form of connection that all the presenters fostered through their works. As she concluded, McClure told the group that she’d been following the work of curator Marvin Heiferman, partner of the art critic Maurice Berger, on Instagram. In March, Berger died of complications from COVID-19 at just 63 years old. As Heiferman grieves, he has been placing old photographs of Berger alongside the spaces he no longer inhabits.

“You know his intimate spaces,” she said. “His desk, his glasses, everything is documented through images. It’s amazing how art can do that for all of us.”

“This is our history,” she said “Each of our own experiences allows for documentation to be very different and sometimes more personal and more difficult in some ways than others. Even though we’re all affected, we’re all affected very differently. It’s important to share our experiences.”

Creative Arts Workshop is on Facebook and Instagram. The organization is currently taking donations here.