Arts & Culture | Theater | Yale Cabaret | Black Lives Matter | COVID-19

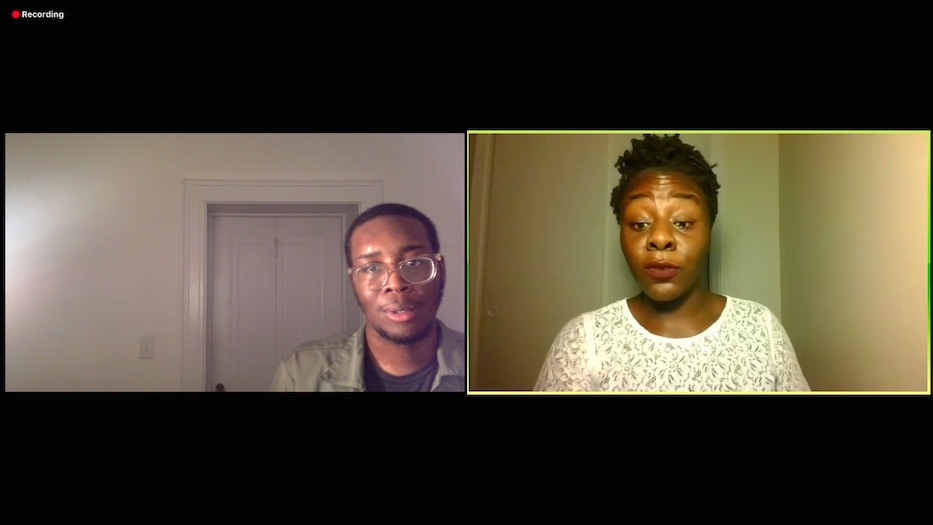

| Zoom. |

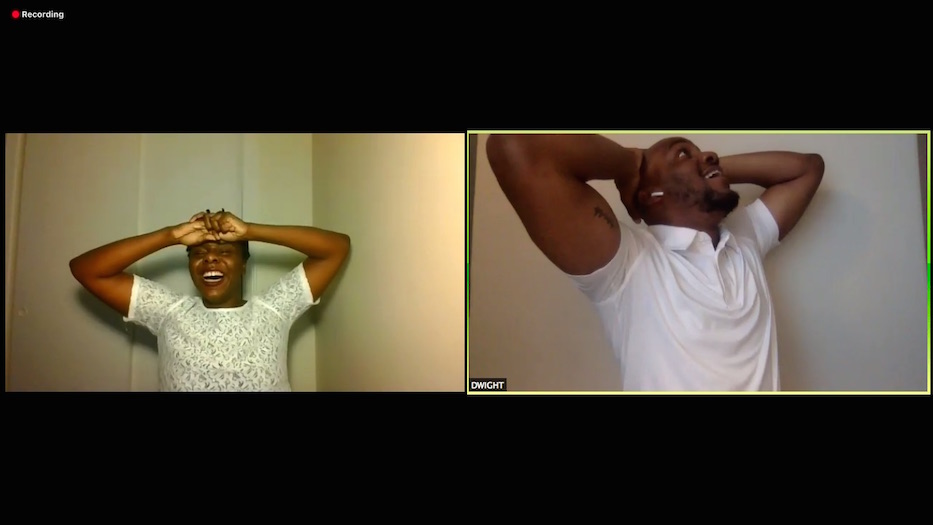

Dwight and Minnie have made it to the moon. They look around; Minnie holds her hands to her mouth as laughter bubbles to her lips. Dwight takes her into his arms. Black skin on Black skin glows against their white clothing. Their tongues twist and reconfigure. Minnie speaks, and even the silence leans in to listen.

“There is no language I’ve been taught big enough to hold me,” she says. Her words fall across the space, a prophecy.

That expansive verse is at the heart of a.k. payne’s Where Pathways Meet, a live reading of which kicked off the Yale Summer Cabaret’s season on Zoom Thursday evening. This year, the summer season is dedicated entirely to Black women playwrights, and presented online due to COVID-19. Its theme, “Meza,” comes from the Swahili word for table.

The first performance was directed by Christopher D. Betts, who is one of the season’s co-artistic directors. It is not payne’s first time bringing work to the Cab: she is the author of Ain’t No Dead Thing, which ran as a radio play earlier this year.

“Instead of asking for a Seat at the Table, we wanted and needed to build a table of our own both as a leadership team and as citizens of a fundamentally flawed society,” wrote the leadership team in a message on its website. “And so this summer’s project, MEZA, was born. Meza, a Swahili word meaning Table, is offered as a unifying theme for our season, and by larger implication, as a way forward for all of us.”

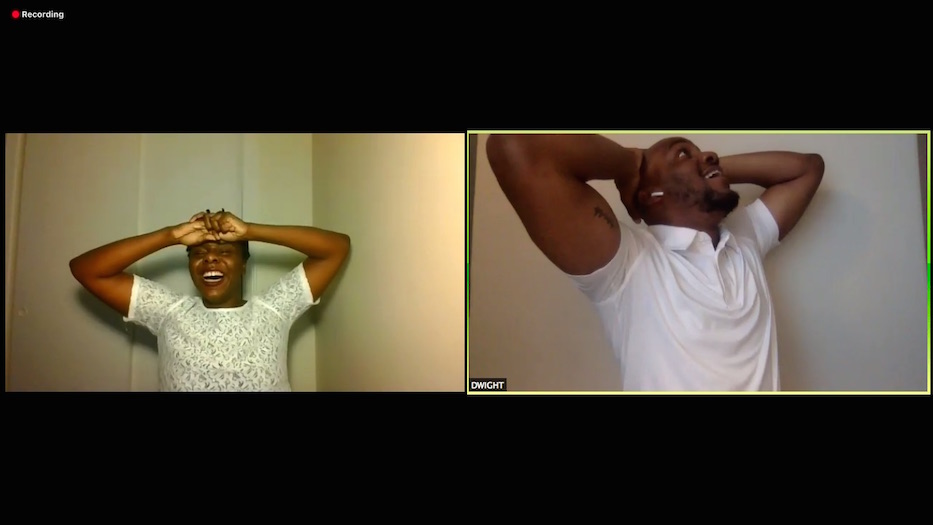

| a.k. payne: “Wrap yourself in a newfound tongue.” |

payne, who is an MFA student in playwriting at the Yale School of Drama, has presented a work that jumps across space and time, a testament to history’s porous and collapsable edges. Where Pathways Meet tells the story of Dwight (Seun Soyemi) and Minnie (Abigail C. Onwunali), a Black couple that leaves earth for the moon in search of freedom. It is often so poetic it feels musical and boundless, like the Sun Ra composition that also bears its name.

Beneath them, the world is literally on fire; they have watched friends and family die in the streets because of the color of their skin and the orders of a king. As the lights come up, Nina Simone’s “Why” crackles over the frame, soaking the audience in a sound that is full of mourning and tribute. With equal parts verse, mythology, and magic, payne chronicles their life on the moon—a life that seems both fully possible and not possible at all on earth. And not because of the pandemic of COVID-19, but because of the pandemic that is racism.

The work layers Dwight and Minnie’s past and future histories onto their present, building a house of memory that holds centuries rather than decades. It is a cavernous space, big enough for their bodies and their words—and the words they do not have—and all the more interesting when compressed through screens and one-inch boxes and fiber optic cable.

Characters blow on moon rocks that become hammers, giving them both the power and permission to build property and a link to the John Henry mythology. The rain falls purple and feels like cotton, at once a thing of genius and oppression, past and present. Their own speech changes as they grow further from an earth that has tried to colonize their bodies, and also their tongues.

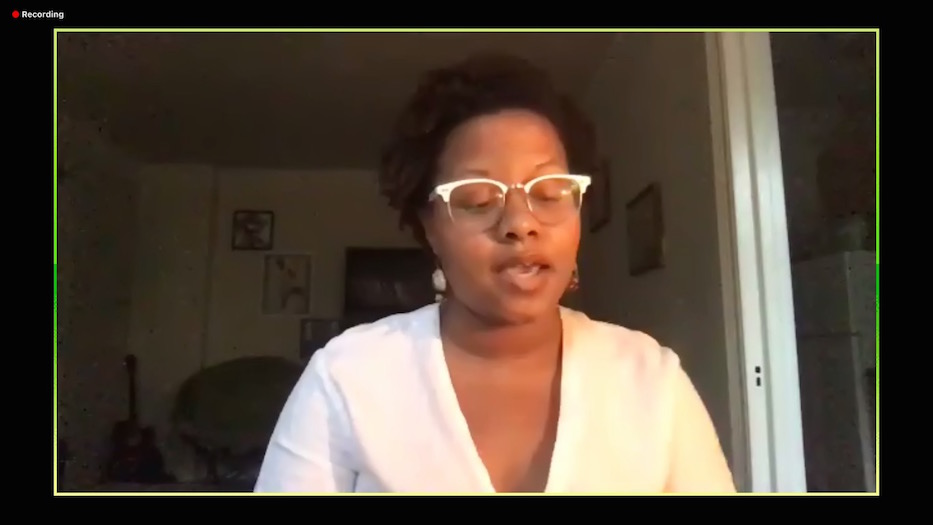

| Clockwise, from top: Anthony Brown, Thomas Pang, and Anula Navlekar in Where Pathways Meet. |

Between scenes that chronicle their life on the moon, the playwright weaves the story of Pvt. Johnson (Anthony Brown), a self-described “Black boy in space” who has been sent on a mission with Pvt. Betts (Anula Navlekar) and their commanding Sergeant (Thomas Pang).

They, too, are locked in this disquieting waltz with words: the sergeant separates “proper” (white, British, colonized) English from all other speech. He chides Johnson for insubordination when he speaks like “those who run,” a euphemism for those who do not follow orders from a tyrannical leader and also those who are from the South. And, the audience gathers after a while, those who are Black.

It’s not clear, at first, whether these storylines are concurrent, or how much they have to do with each other (payne asks her viewers to trust the process, and they are rewarded if they do). Her choice of speech as a framing device works: it is through its colonization that humans name and amplify differences. It is how, well before Linnaeus and Blumenbach, humans justified oppressing other people. In the play, payne treats it as almost a physical force, where words follow the basic laws of motion.

To white, for instance, there is Black. To male, there is female. To rich, poor. To strong, soft. To those who comply with the King’s orders, there are those who attempt to run away, and who are dubbed insubordinate, defective, disposable. To a liberated society, there is the creation of race itself, which in turn enables the creation of racism.

payne also makes it her business (and, by extension, the audience’s) to know more about the space in between words, where things are unwritten and unsaid but still very much alive. Think Tyehimba Jess' 2016 Olio, with a specific pivot to gender. She probes the intimate connection between white supremacy, patriarchy, and misogynoir, seeing what will happen if she makes it give. In a brief introduction to the performance Thursday, she encouraged viewers to “wrap yourself in a newfound tongue” as they listened.

“This play uses line breaks to say what I cannot say,” she said.

It turns the work itself into both a poem and an appeal. In a scene near the beginning of the play, Minnie and Dwight have reached the moon, taking in the possibilities of its expanse. Minnie slides into speech comfortably, willing the universe to do her bidding with a kind of mutual awe and respect.

Dwight, meanwhile, falters. When he is asked to envision his own free future, he literally cannot find the words. He looks to the space around him, marvelling at this untapped moonscape. He opens his mouth: “If there were a land where we were free, I’d—”

He stops. His arms span all the way out. He tries again. “I’d … I’d … I’d ….”

It is a metaphor that keeps giving throughout the work. payne is keenly aware of the ties that bind language, memory, and trauma—and the way one bleeds into the other. Dwight’s tongue does not stop because he is unimaginative; it stops because revisionist history has a way of scrubbing the possibility of freedom from one’s mind.

It is no mistake when Betts, gentle and sincere in Navlekar’s able hands, says that she still wants to come home “even if I am three-fifths of a body.” No mistake, also, when Johnson struggles to claim his own memories as fact versus fiction. And no mistake when, masterfully, payne creates a world in which the language of seeing separates real and performative allyship.

Zoom is not the Cabaret’s Park Street black box, but it works. Onwunali commands the space, her voice resonant and rich enough to be on a stage. There’s something specific about watching a face that is mere inches, and also miles, away: its movements are magnified and literally flattened all at once.

Through her lines—and gestures, for that matter—come echoes not only of Black women at the forefront of social justice movements, but also land reclamation, sovereignty, and a creation myth that predated stolen people on stolen land.

She is not alone in making this cold, strange internet landscape into a performance space: Brown and Navlekar perform their lines with so much sincerity that it is possible to see them side-by-side, floating in a capsule with no gravity to hold them. Soyemi learns that Zoom does not have to limit physicality, and captivates the whole space. Pang reveals a backstory layer by layer, careful to hold his cards to his chest.

Thursday’s reading found characters apart but together, in a series of one-inch, sometimes pixelated boxes on a screen. And still, across the distance, it felt right on time for both the season, which has designed a small community spotlight page (Black Lives Matter New Haven, Love Fed Initiative, People Get Ready Bookspace, CT Core, Citywide Youth Coalition, Elm City Lit Fest and Students for Educational Justice are all conspicuously absent) on its website, and for the city.

Last weekend, State Rep. Robyn Porter spoke to a crowd in Newhallville, urging attendees to advocate for police accountability and transparency as it went to the State Senate. Five days later, 20 of the city’s youth marched through downtown to the Union Avenue headquarters of the New Haven Police Department, to advocate for defunding the police and getting cops out of schools by August.

And less than 48 hours before the play premiered on Zoom, State Sen. Gary Winfield stood on the floor of the Connecticut State Senate in a tan suit, fighting for a police accountability bill that Gov. Ned Lamont signed on Friday afternoon.

It was just after 3 a.m., and he had just punctuated policy reform with an a cappella version of “Eyes On The Prize.” His eyes were already wet. His voice broke on the song’s final call to “hold on.” In another universe, payne’s characters may have finished a penultimate run-through.

"I'm tired of holding on,” he said. “We talk about people that were enslaved in this country and that ran away. You know what they ran away for? They didn't run away for civil rights. They ran away for liberation. That's what this work is. This is liberation work.”

The Yale Summer Cabaret returns with Daughters of the Confederacy by Angie Bridgette Jones on Aug. 8 at 7 p.m. More information, including registration on Zoom, is available here.