LGBTQ | Arts & Culture | New Haven Pride Center | Visual Arts

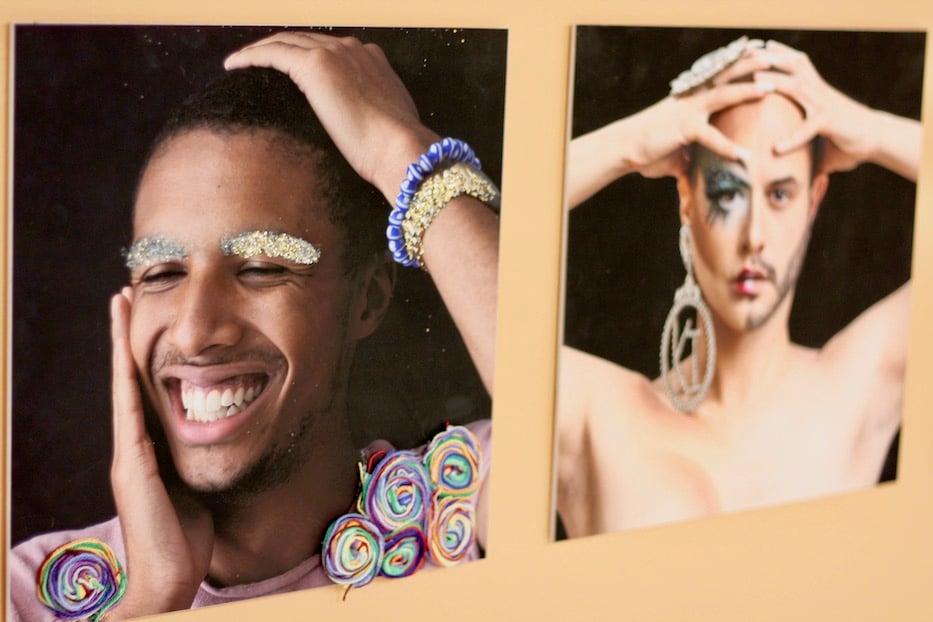

| Cate Barry’s LGBTQ Collaborative Portrait Project is one of the works on display at Self Love: Personal Expressions of Care at the New Haven Pride Center through Feb. 27. Lucy Gellman Photos with permission of the artists. |

The glitter is layered on thick, smudge of silver and gold over the eyebrows. It drips to the wrist, where it covers a watch in a crust of brilliant color. Just inches away, shoulders rise with ease, lifting bright rounds of yarn as they go. It’s hard to look at the image and not burst right into a grin.

But is it self-love? What does that even mean?

The New Haven Pride Center is asking those questions in Self Love: Personal Expressions of Care, a new group exhibition running at the center’s Orange Street gallery through Feb. 27. The show feels right on time, asking viewers to consider queer self-love and self-care a time when members of the LGBTQ+ community remain under attack.

“What do you do to love yourself?,” asks an introductory text. “How do you express what is uniquely you through art? How do you care for yourself, and is that enough?”

Across the center’s gallery, artists have answered the call in multiple media. In photographer Cate Barry’s LGBTQ Collaborative Portrait Project, a series of photographs wink out, vibrating with color. In place of conventional, head-on portraits, Barry has worked with the subjects to alter the portraits themselves. They are thrilling to look at, a riot of color that beckons

In one, trans activist Karleigh Chardonnay Merlot holds up an image of her driver’s license, breaking a huge grin. One can see that identifying details have been colored over with blue, white, and pink—the colors of the transgender pride flag. As she grasps the license gingerly, her fingers are covered with text, reading “Realness/I Am Karleigh/I Will Not Apologize/For Saving My Life!” Her sweater glitters with red and white stripes of the country's flag, letting the viewer imagine a world where trans rights are American as apple pie.

Others are whimsical and celebratory: subjects wear glitter and sport bright, collaged-on mustaches and eyeglasses. They paint rainbows over swaths of their skin and decorate their shirts and necks with strings of words that hang like jewelry. A few weave rainbows of yarn into their hair and onto their clothes.

In a curatorial move that is as effective as it is affecting, Pride Center Director Patrick Dunn (who is also photographed as one-half himself, one-half drag queen Kiki Lucia) has left a number of blank spaces for people who are not ready to be photographed. It’s a quiet, powerful reminder of how queer bodies can be policed in the most intimate and unassuming of spaces—in their homes, their bedrooms, in their houses of worship and in their communities.

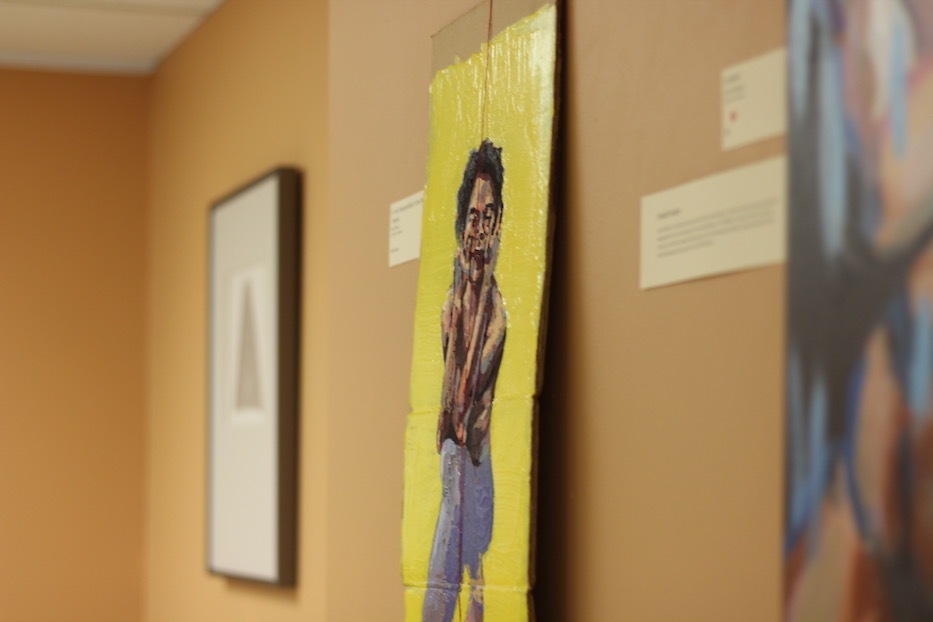

Barry’s portraits, which mark the entrance to the show, are a jumping-off point into a world where self-love becomes synonymous with self-discovery. Artist Jisu Sheen leaves her work wide open for the viewer in Let It Make You Kinder, Softer, Gentle (pictured above), where a section of a woman’s face had been jumbled, pixelated and painted over with red and blue paint.

It’s a device that pushes the viewer to look closely at what is exposed—an eye, looking right out of the frame—and what isn’t. The longer one looks, the more emerges: a smudge of grey and pink beneath the one eye, an outline of red on the figure’s hair, less like a halo and more like a boundary. Sheen’s choice of oil on wood gives the viewer a chance to study the substrate itself, watching how the paint bleeds into and streaks on the grain.

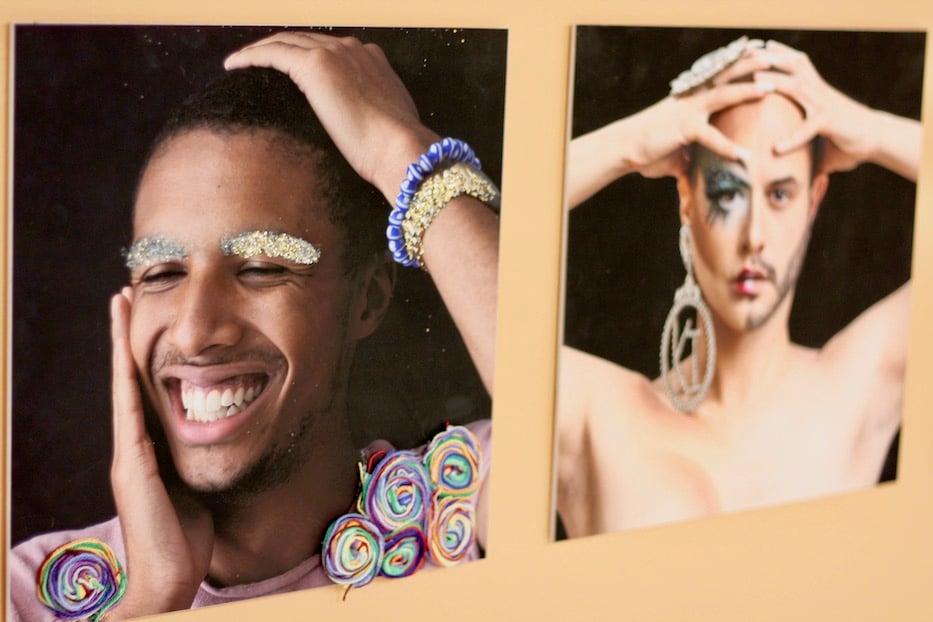

Sheen has written about the influence of adrienne maree brown (Pleasure Activism, Emergent Strategy) on her work, and it shows. In her It’s Your Responsibility to Stay Well Rested, a figure crouches shirtless, hugging themselves. Evey close. Palms fill themselves with skin and cheekbone. The figure presses one foot into the ground. A yellow backdrop and piece of red yarn bisecting the image make it impossible to look away.

A poem is attached to the base, walking the viewer through their own liberation and perhaps the figure’s as well. The words—an excerpt reads “you don’t have to love me all/the time. Let me do that./You don’t have to hold you up. Let/The earth do that”—hit surprisingly hard.

To pieces that evoke, amuse and delight, other artists have also provided an education. In “Since I Stopped Being A Girl,” trans advocate, professor, and cartoonist KC Councilor uses graphic art and a whip-smart, matter-of-fact sense of humor to walk viewers through how his (or his character’s) day-to-day has changed.

Across two pages of neat, black-and-white frames with minimal color, Councilor gets a new haircut, smiling in the mirror. He offers plates of food to a partner, always giving her the better of the two. He takes out trash and lifts boxes, beads of sweat flying off his face. Frame by frame, the viewer takes it all in.

The images aren’t just fun to look at; they also mark Councilor dropping essential knowledge on his viewers. For an LGBTQ+ advocate, ally, community member or accomplice looking at the work, maybe the information isn’t new. But for those who don’t understand or are skeptical of trans identity and the process of transitioning, he walks them through it in clean, straightforward language and form.

It’s an uncomplicated, demystifying look at life during and after transitioning, where huge life changes (the introduction of hormone replacement therapy, for instance) are placed on an extremely human scale. The use of cartooning, too often cast off the pedestrian cousin to the fine arts, works here. Councilor, without a hint of sanctimoniousness or judgement, leaves the viewer wondering what else they don’t know.

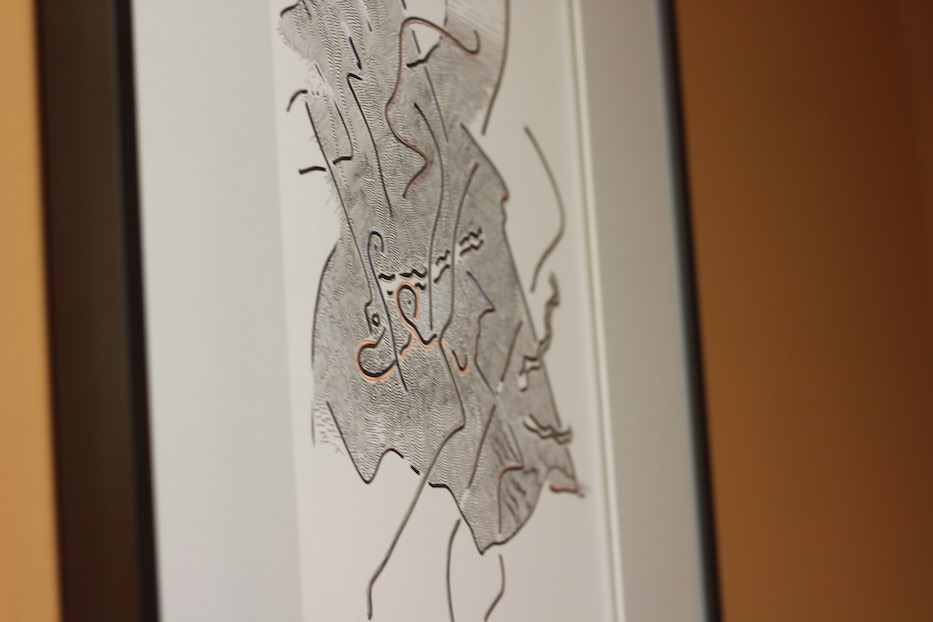

Others still have kept their work abstract or surreal, speaking to the more meditative aspects of self-love. Jonathan-Joseph Ganjian, whose large-scale works rocked the gallery in 2018, has returned with a smaller canvas in which paint is layered, a scrawl looping across the front of the work.

In black, white and orange, artist Robert Bienstock turns the viewer inward with two line drawings, both completed while the artist was going through a breakup. Sarah Silvercool delights with a wash of color, building a sort of dream-world in the space of a single canvas. So too Don Houston and Sue Czark, whose encaustic of a heart bursting with light adds little warmth to the room.

Together, they suggest a community lurching toward something that looks like taking better care of oneself, and also one’s village. As the show’s final work, Dunn has installed an interactive display with huge pieces of paper and black and green markers, so that viewers and artists alike may add their own voices to the mix. It is one of the most fun works in the show, as one reads answers to the questions “What Is/Self-Love?”

“Treating myself with dignity,” reads an answer surrounded by tiny, twinkling stars.

The New Haven Pride Center is located in the basement of 84 Orange Street, New Haven CT. The gallery is open Tuesday through Thursday, 3-6 p.m.