Culture & Community | Education & Youth | Integrated Refugee & Immigrant Services (IRIS) | NXTHVN | Arts & Culture | Artspace New Haven | Arts & Anti-racism | Hill Regional Career High School

Aime Mulungula photographed at mActivity in New Haven's East Rock neighborhood. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Aime Mulungula grew up searching for resources that could support him as a budding artist and Congolese refugee. Now just a year out of high school, he's working to create those same stepping stones for his peers, particularly young artists of color.

That's the idea behind Lebon Studio, a new website, art archive, exhibition series, and clothing brand that Mulungula is rolling out this summer as he balances his painting practice, a full-time fellowship, and studies in business management and visual arts at the University of Connecticut. He is currently a fellow at the Peter J. Werth Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation and a rising sophomore at the college.

"There were a lot of young artists like myself who never got opportunities," he said, sitting among snugly packed bookshelves at mActivity in East Rock last week. "The problem is, they have talent— right?—but they don't have the opportunities to grow and excel because of the lack of resources they have in the neighborhood."

From its name to its mission, Lebon is inspired by his own path to artmaking, and the number of systemic barriers that have stood and remain in his way. The fifth of nine children born to Congolese parents, Mulungula grew up in a refugee camp in Tanzania where he and his siblings had very little. From a very young age, he knew that he loved artmaking ("I was the art kid," he said with a small, certain smile), but wasn't able to act on that dream.

"I was never asked, 'What is your dream career, your dream job?'" he said. "We never had that question at all. We were just living there, surviving basically. We didn't have anything to support that."

Aime Mulungula presenting at the Horizons Summer Program at the Foote School in 2021. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

In those years, he said, he also wasn’t known as Aime, but as Lebon or Le Bon, named in honor of his great uncle. That changed when he was 11 years old, and he and members of his family came to New Haven. According to his parents, his name changed during the immigration process, somewhere in between getting refugee status and a hard-to-understand mountain of paperwork with which they were tasked.

Initially, his family moved to Westville Manor in the city's West Rock neighborhood, where Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services (IRIS), helped resettle them in a new country. As a quiet, shy sixth grader at Fair Haven Middle School, he spent a year learning English before transferring into general classes. Five years ago, he went onto classes at Hill Regional Career High School, which ultimately became his launchpad into arts and entrepreneurship.

He also flexed his artmaking muscles, using whatever resources were at his disposal. Early drawings of his, some from IRIS’ 2015 summer learning program, feature teachers and students with speech bubbles beside their mouths, talking about school on a backdrop of lined notebook paper. In one, an anime-esque rendering of a student looks toward the front of the classroom, his hand raised into the air. A book sits, spine up, on the desk. On the board, an equation reads “3 + 2?”

“Me, I know this question,” the student says. Behind him, a fellow student declares that “I like school very much.” A satchel, shaded to show its depth, hangs in his left hand. A plane floats at the far right of the image, showing their journey to the U.S.

Some of the examples Mulungula brought to a class at the Foote School last summer. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

“It's almost like he was doing graphic novel type work,” said Ashley Makar, outreach coordinator at IRIS, who taught him in a storytelling workshop that year. “Years later … It's amazing to see his work and his vision for what he wants to do. I'm so impressed and so glad to see him soaring like this.”

Even as he excelled in his classes, Mulungula said, he had a sense that the odds were against him. Kids who looked like him—who were young and Black, who were refugees, who were poor—didn’t have the same access to fellowship and internship programs, extracurricular activities, or art classes as their whiter, wealthier peers. They had the same knowledge, he said—just not the resources to apply it in the way that they dreamed of.

At school, Mulungula also found that his classmates talked about Africa as if it were a single country, rather than a continent with over 1.2 billion people. They asked him if people lived in huts. They had no sense of the thriving, vibrant culture flowing from its 54 countries, or the multiplicity of a diaspora that was centuries old.

Artmaking ultimately paved the way through the noise of those stereotypes. During his first two years at Hill Regional Career High School, he became involved with the educational nonprofit The Future Project, as well as Artspace New Haven and the Dixwell-based arts incubator NXTHVN. Jay Kemp, then a dream director for The Future Project (he is now student program manager at NXTHVN), remembered watching as Mulungula rapped in Swahili at a lunchtime open mic. He was floored.

"I saw his willingness to step out and do this different thing, the willingness to be bold,” Kemp said. “I think that was the moment that I was like, 'I want to give him all the support that he needs.'"

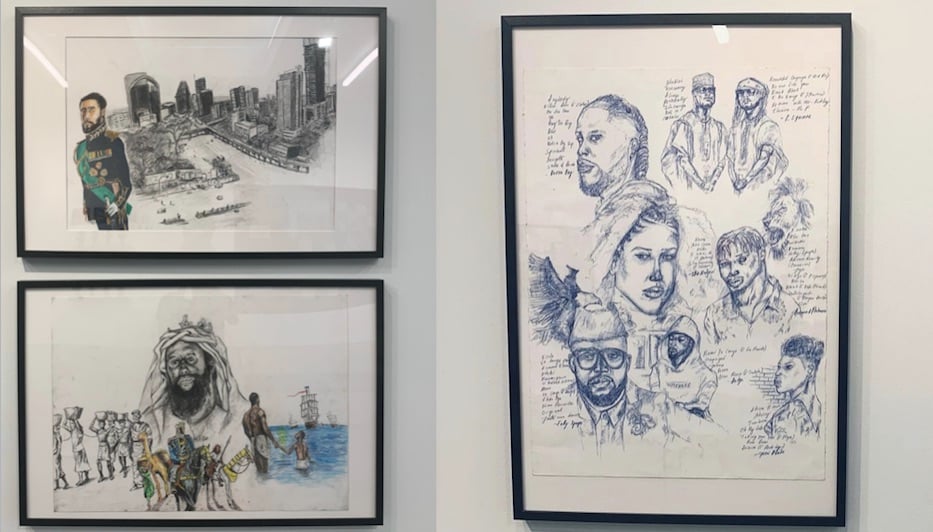

And he did. Kemp encouraged Mulungula to get involved with NXTHVN, through which he joined the space's then-nascent apprenticeship program. Paired with multimedia artist Jeffrey Meris, Mulungula dedicated his work to addressing—and debunking—his classmates’ misperceptions of Africa. He started with his own experience in Congo and Tanzania, where he still has family, and then branched out to East Africa, and then to the entire continent.

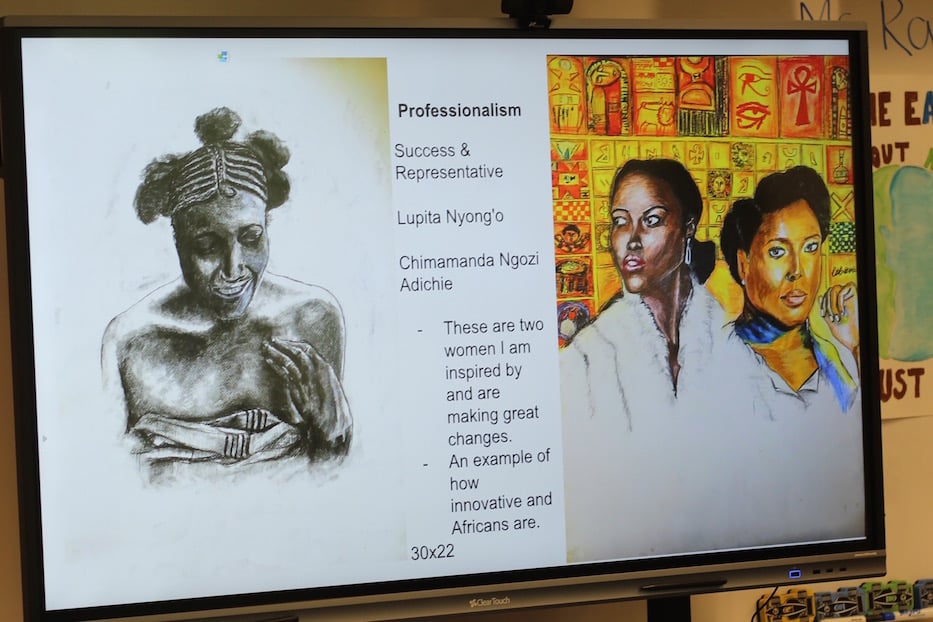

Images of Haile Selassie, Mansa Musa, and Burundian writers that Mulungula worked on during the pandemic. Aime Mulungula Photos and artwork.

In the finished pieces, Mulungula has dug deep, with a sense that there will be infinite stories to tell, and a sprawling, curious palette with which to tell them. In one image, a Maasai warrior stands facing the viewer, folds of red cloth glowing against his skin. In another, the artist tells the story of the Mali ruler Mansa Musa, drenching the work in history as images of enslaved West Africans and forced migration appear beneath Musa’s visage.

In another, men appear in sharp, tailored and buttoned jackets, fedoras cocked just so atop their heads, in a reminder that high fashion is a thriving part of the continent. Read more about those works here, here and here.

He also spent several hours each week in Meris’ studio, learning firsthand from the artist. When Covid-19 hit the city, he and Meris isolated physically, but stayed in touch with each other multiple times a week, continuing to deepen their practice. In some ways, both said over separate interviews, the ability to talk about being artists in the pandemic brought them closer together. When it was safe to do so, they returned to a hybrid working environment.

“He's my heart,” Meris said in a phone call Monday night. “I'm so incredibly proud of him, I can't even begin to tell you … I know how hard it can be to be an artist, much less an artist and an entrepreneur at the same time.”

That was also the catalyst for Lebon. After Mulungula graduated from high school last year, he found himself suddenly unmoored—particularly after starting his freshman year at the University of Connecticut. The campus overwhelmed him. He didn’t know many of the members of his class. He worked around the clock to stay on top of his classes in business management.

"I was lost,” he said. Then he thought back to his artwork, which he currently does from a home studio in his bedroom. "I thought, this is something I want to do," he said. In the spring of this year, he declared a minor in visual art, and started making work about self-reflection and self-discovery. In particular, he has focused on several portraits of himself.

Photo courtesy of Aime Mulungula.

In one, he poses against a turquoise background, his eyes fixed on something in the distance. The word LEBON, printed in white, stands out from a navy blue sweatshirt covering his shoulders, neck and torso. It rumples and folds with the movement of his arms as they cross in front of his chest.

For viewers who have followed his work for years—and maybe those who are also coming to his work for the first time—it’s striking how grown up this version of the artist looks. Gone is the younger, sweet-faced and wide-eyed Aime that appeared just two years ago in a self portrait at NXTHVN, with a backwards baseball cap and a plaid shirt hanging off one shoulder. Here, he looks like he knows exactly what his next move is, and how to make it.

Lebon—literally “the good” in French, and titled after the name his parents gave him almost two decades ago—has bloomed out of that impulse. For the next six months or so, he plans to focus mainly on his own artwork, with a mission to support fellow artists within six to seven months. On small batches of shirts and sweatshirts that bear the brand’s name, he plans to print images of his paintings, so that people can literally wear his art. Ultimately, he wants to create opportunities for young artists in Tanzania, Congo, and Uganda—where he still has family.

"I wanted to have a platform where I could, first things first, sell my own artwork, and then have some level of service where I could help young artists, consult them, give them mentorship,” he said. “That way they can grow through my mentorship.”

“The whole idea of it is to promote the good,” he added. “What the media promotes is the negative aspect not only of African culture, but of Black people as well. It portrays that negative of them as being bad, it denigrates us. This is to show integrity, power … anybody wearing it can embrace who they really are. There’s so much good going on that people don’t get to see.”

Photo courtesy of Aime Mulungula.

Already, he’s become a role model. At home, he mentors his younger sister Riziki as she grows her own artistic footprint. During IRIS’s 2022 summer learning program, he gave a presentation on Lebon Studio to young refugees, some of whom had only recently arrived in the U.S. Eventually, he wants to grow it into a brick-and-mortar incubator space like NXTHVN—but is moving one step at a time to get there.

As he begins his sophomore year at the University of Connecticut, he said he hopes to partner with arts organizations across the city and the state, from the new Stetson Branch Library and Artspace New Haven to the Wadsworth Atheneum of Art. In the fall, he plans to hold a small solo exhibition at the University of Connecticut. He does not yet have a location for the show.

Zeenie Malik, community engagement and events specialist at IRIS, said she is excited to see how Lebon Studio unfolds. Over a year ago, she sat down with Mulungula to talk about his artwork, and felt aware that she was talking to someone “wise beyond his years.” Then in June of this year, she watched him tell his story in front of 100 people for World Refugee Day.

She looked at Lebon as an extension of the work that he started at NXTHVN, using artistic skill as a teaching tool.

“Instead of just feeling alienated or upset or mad, he took this positive spin with it,” she said of his artwork. “He was like, ‘I need to educate people through my artwork.’ For someone so young to have that mentality … he doesn't shy away from a challenge.”

Learn more about Lebon Studio here.