Fair Haven | Arts & Culture | Robert Greenberg

| “Artisans made these things,” Greenberg said on a tour of the space. “Every one of these artifacts, every one of these objects, really is a piece of art.” Lucy Gellman Photos. |

There is too much to take in at once, which is the point. From the front of the space, a graffitied desk greets the viewer, tipped on its side to reveal a spray of neon pink, swells of black and green and white. Dried sheaves of tea-colored tobacco spin in a corner. Old order sheets from Louis’ Lunch wilt on a wall, covered in red crayon. A tin emblazoned with Handsome Dan winks out somewhere further back. He's vying for attention.

But is it one man’s marauding trip down memory lane, or a cabinet of curiosities that tells a story of New Haven? And what story is it, exactly?

Artist Robert Greenberg is attempting to answer that question as he prepares to move his massive collection of New Haven history and memorabilia for a second time in three years. Currently, the collection lives in a 3,500 square foot space in Reclamation Lumber on Grand Avenue, where he relocated after getting the boot from ACME Furniture three years ago, when his father sold the family business.

Robert Fecke, who runs Reclamation Lumber, confirmed Greenberg will not be renewing his lease next year. He declined to comment further.

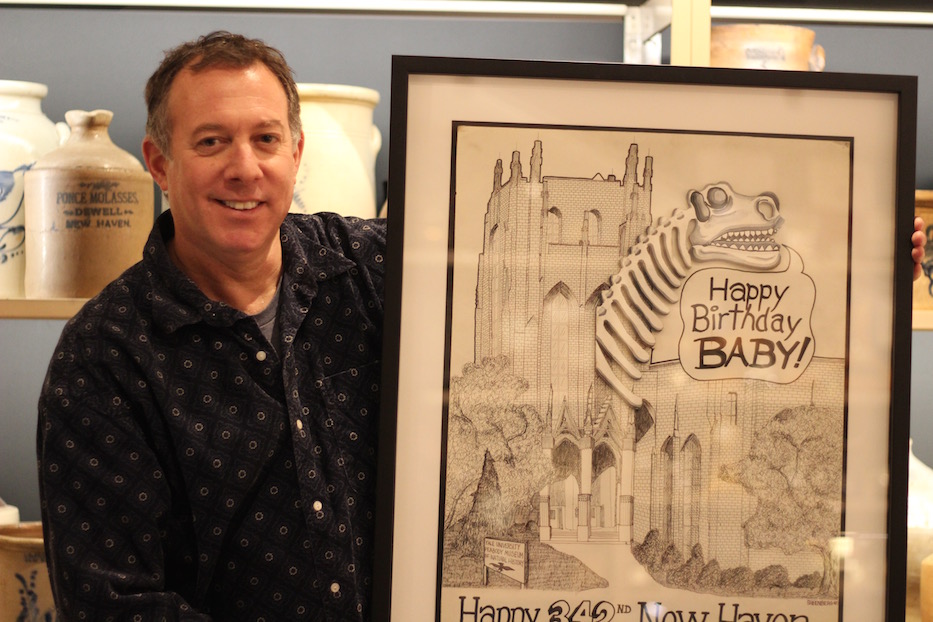

| Greenberg with a poster he designed for the city's 342nd birthday. After he won a contest for the drawing, Mayor Ben DiLieto sent him a letter that now hangs, framed, on his wall. "I am proud of you," reads the final sentence. |

“This is not my collection, it’s our collection,” Greenberg said on a recent tour of the space. “People are starved to know what happened here. And they love it. It’s that link that everyone kinds of needs.”

“It is constantly growing, changing, and transforming,” he added, comparing his impending move to Revolutionary War battles fought by George Washington and William Howe. "You never know what somebody’s going to talk about here. Their memories start to surface.”

The move has left him worrying about the future of an ever-expanding collection he calls “a celebration of one of the greatest immigrant societies in the world.” Christened “Lost In New Haven,” the estimated 5,000 objects span popular culture, ephemera, architectural fragments, textiles, and relics of New Haven haunts, from the once-loved Hyperion Theatre to the Coliseum to the Anchor Bar. It is supported largely by Laura Clarke, executive director of Site Projects New Haven, and artists Roz and Jerry Meyer.

“This is a brilliant long term endeavor with incredible benefits to New Haven if we can keep Robert moving forward,” Clarke said in a phone call Wednesday afternoon. “He has the capacity to engage the city as if it were a fun house or a carnival. There won't be rides and there won't be spooky dark tunnels, but there is an unending potential for people to hear things and see things that they haven't heard, and to understand how rich the history of New Haven is.”

The story of “Lost In New Haven” starts not just with ACME’s closure in 2016, but with Greenberg’s own love affair with the city and its residents, which began when he was just a kid. Greenberg grew up in New Haven, watching the city transform around him as urban renewal took root and then threatened his father's business.

During his youth, the Peabody Museum of Natural History became a de facto second home, so much so that he integrated its massive brontosaurus into a birthday card for the city under Mayor Ben DiLieto. He credits his time at Richard C. Lee High School (now Hill Regional Career High School) and the Educational Center for the Arts (ECA) for giving him a grounding in visual art that launched a career in design.

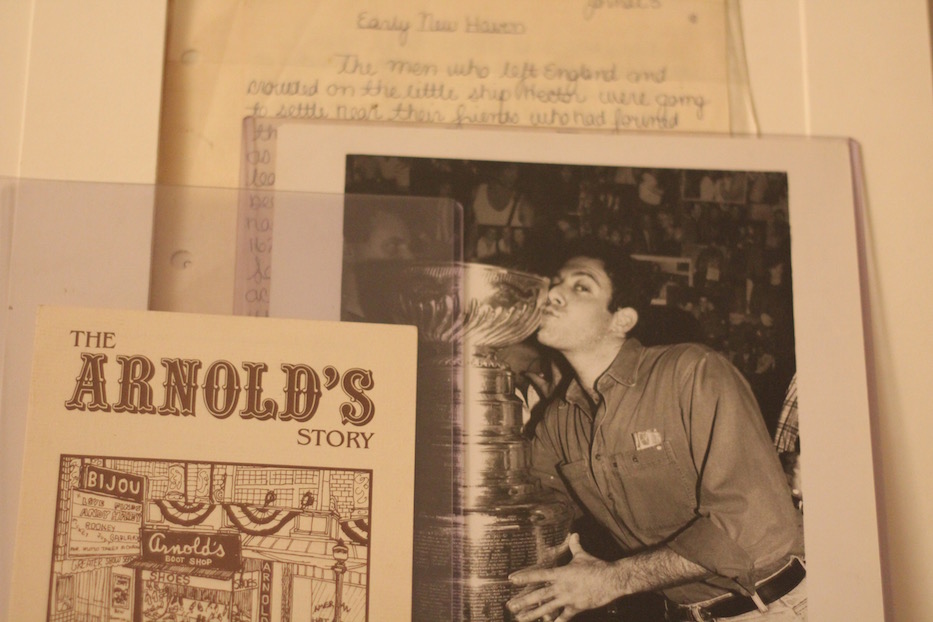

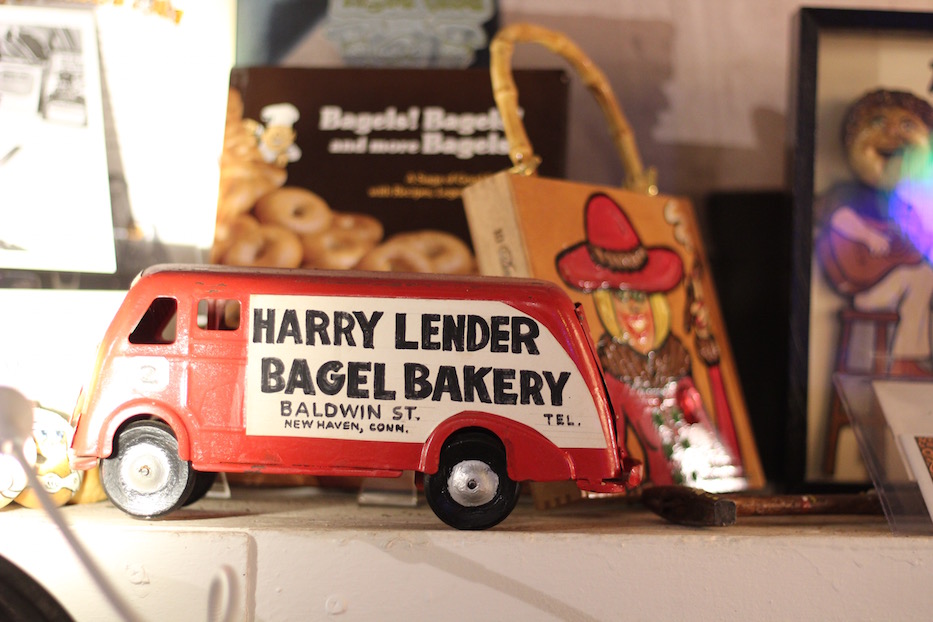

Collecting was in his blood even then: his maternal grandfather Simon was an antiques dealer, and his paternal grandfather Joseph started ACME after immigrating to the city from Russia. His great uncle Willie Evans was a pioneering designer for Lender’s Bagels; his uncle Joel Evans was an artist. Their work inspired Greenberg, who went on to study design at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) after his time at ECA, then practiced in New York City for 26 years.

| Greenberg, who keeps a few favorite old, handwritten papers from school in his office, bemoaned the loss of New Haven history in the city's public schools. |

During those years, he found himself fascinated by the practices of visible storage that he saw at the New York Historical Society. He studied the way that warm lamps and spotlights made objects feel theatrical and also alive, as if they were breathing right out of the past. When he returned to New Haven and started building a teachable collection, those displays were never far from his mind. Meanwhile, he worked on preserving ACME’s Crown Street home, repairing the roof when Hurricane Sandy ripped through town in 2012 while picking up projects that dealt with the city’s history.

“Art was always in my system,” he said. “I felt if I could acquire objects and put them in vignettes, then I could tell the story of New Haven.”

But at ACME, Greenberg didn’t feel like he had enough space to tell the story he wanted. While he originally protested his father’s sale of the building in 2016, he said he now realizes that he had outgrown it. Objects were pushed together: a section of the Lincoln Oak sidled right up to rows of casings from the Winchester Repeating Arms Company. Old earthenware jars, still fragrant with the molasses they once held, weren’t far from a handful of tiny sculpted Lender’s bagels with facial expressions.

Greenberg left ACME in late 2016. Fecke, who Greenberg originally had met while vying for a section of the Lincoln Oak years earlier, offered the space for temporary storage. The move and ensuing reset, during which Greenberg said he cleaned the space “all by myself,” gave him time to think about the cabinet of curiosities he wanted to create.

| Greenberg's maternal great uncle, Willie Evans was a pioneering designer for Lender’s Bagels. |

He believed that the interest was there : the community rallied and held fundraisers, local donors emerged from the woodwork to help with rent, tours started coming through the space. He estimates that he has had over 40 tours, including several school groups and sessions at the International Festival of Arts & Ideas, since last fall. On a recent Monday, a couple dropped in on a whim and stayed for two hours.

Elihu Rubin, associate professor of urbanism at the Yale School of Architecture, praised the collection for its sweeping view of New Haven history and teaching potential, calling it a possible draw for both tourists and residents.

“One of the things that really draws people back to cities is a sense of history,” he said, noting that young people are returning to cities for their density, scale, and sense of evolving history. “This [collection] takes materials from New Haven’s past to form this incredible sense of pride and place. It's why I really think a collection like this is such a big asset to the city.”

“It really is that good,” he added. “It really is that much stuff. The radio stations. The pizza places. The Anchor Bar. It is its own museum collection. It's just a lot of stuff to appreciate.”

| Multiple displays, arranged on an imaginary line that spans the room, weave together the history of carriage wheels, early bicycles, and current bike landscape, including the Devil's Gear Bike Shop. |

Greenberg has organized the collection in a series of three-dimensional vignettes inspired by vanitas, the detailed, dramatic still life paintings that came out of sixteenth and seventeenth century Holland. He’s also taken a page from artist Mark Dion’s contemporary memory boxes, which have been displayed in London and New York. Some of the shelving comes from local philanthropist Wendy Hamilton; other units he built and lit by hand. It is a sprawling display arranged thematically rather than chronologically, intended to flow back and forth through the city’s history.

“This is a gateway to another world,” he said. “I believe in the spirit world. I firmly believe the other side guides me. These, in here, are the souls of these objects.”

And in many ways, it is. Close to the entrance, an upturned desk radiates recent New Haven history, recalling Greenberg’s work with students, local graffiti artists, and Lou Cox of Channel 1 Skate Shop to paint furniture and place it in ACME’s big, shifting storefront display in Crown Street. There are pieces of the city every which way one looks: boxes of bandages from the Seamless Rubber Company, squares with moveable type, and whole shelves dedicated to the history of Yale University, with smooth football helmets and Handsome Dan memorabilia that gleam in the light.

Up and to the left, a burst of neon flickers into focus: the sign from the now-empty Rubber Match storefront on Whalley Avenue, where it beckoned like a set piece from “That 70s Show” for decades. After the store went out of business in 2018, owner George Zito gave Greenberg the sign because it held local history, designed by local Curtis Gaulin of C & G Signs. The shop still operates out of the city’s East Shore neighborhood.

It’s in good company: Greenberg has also installed the much-beloved sign from the old Anchor Bar, which closed suddenly and much to the public’s dismay in 2015. There is a history of beer and brewing in New Haven, a through line that weaves wood carriage wheels to the early bicycles that once rolled through the New Haven Green to the Devil’s Gear Bike Shop and the city’s current economy.

The objects span Greenberg’s internet purchases, amateur archaeological digs, and gifts from local merchants and friends. Others, like the Anchor sign, are surprise finds: it was half-submerged in the snow in a Connecticut backyard.

Nearby, names of beloved businesses past and present wink out: a sweatshirt from the late, great Yankee Doodle, a clock advertising Hull’s beer, waxy order sheets from Louis’ Lunch and wire racks of empty, clean pizza boxes with photos of the immigrants that kept the joints running. A time-lapse hologram of Chapel Street beckons from one wall, showing how the street has changed over decades. In this view, it's not specifically for the better.

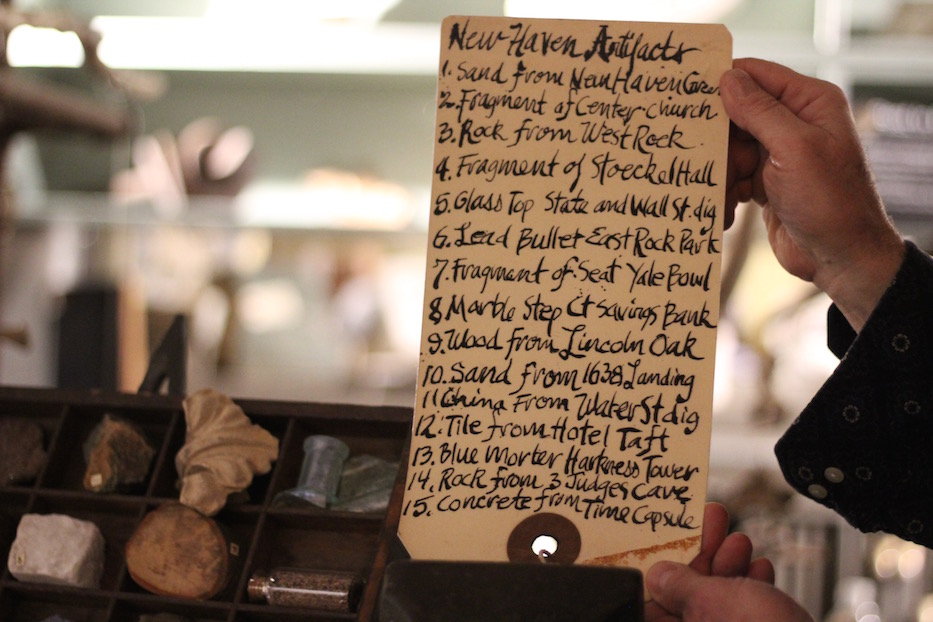

The display keeps going, hopping through history with no apparent end point. On a section of the Lincoln Oak, pressed and polished by Fecke after the tree fell, Greenberg has placed notes on “what New Haven saw” on rings of the tree that correspond with the years the events took place.

There are big moments: the beginnings of World Wars and armistice treaties, Theodore Roosevelt’s death and John F. Kennedy’s assassination, Jim Morrison’s 1972 arrest for indecent exposure in New Haven. On its outside layer, Greenberg has placed a newspaper clipping from October 2012, just hours before Hurricane Sandy pummeled the East Coast and brought down the oak with its winds.

Across the room, he has laid out a story of how A.C. Gilbert got to the Erector Set by riding the train from New York, a story that ends in happy kids with their Erector Sets, decades of economic history and a labyrinthine factory with an afterlife in art and small business. He has lined up typewriters that look like they could produce the city’s whole history one tap-tap-ding at a time.

Greenberg said he has focused on these cultural connections in an approach intended to drive home the importance of the past on an increasingly digital present. In a back room, shelves of old, evolving telephones sit beside a display of clocks, channeling both the District Telephone Company and New Haven Clock Company that so defined the city—and the country—as technology lurched forward.

It’s a hodge-podge that hangs between acute nostalgia, time capsule, and requiem. In the middle of the space, Greenberg has collected and arranged 122 bricks from the old Gatehouse Building, a section of the Brewery Square Apartments complex that stood vacant for three decades and then came down last year, on an order from the city.

He has arranged timepieces that were designed as airplane propellers after Charles Lindbergh’s first transatlantic flight, showing the influence of a national hero on the local economy. Back in the front room, there are steps from the old bank building on which thousands of feet have walked.

Under glass in another case of New Haven treasures, there's a record book showing that Long Wharf architect and freed slave William Lanson purchased a shovel. On the wall behind it, reconstructed sailboats float on a tiny version of Lanson’s retaining wall, with blue tulle and rocks that Greenberg salvaged from beside the actual wall.

"I just think it's so important that we teach this history," Greenberg said.

More recently, Greenberg said he’s also been thinking about the fact that it’s still an incomplete history, filtered through a personal rather than an academic or museological lens. On a recent visit with the artist and NXTHVN Founder Titus Kaphar, a long conversation about George Washington’s enslavement of Black people gave Greenberg a more complex understanding of the general, who he had revered without a critical eye for decades. Now, prints of Kaphar’s work hang beside a miniature of Washington.

“There are angles that it so desperately needs,” he said. “You need the African-American perspective. You need the Hispanic perspective. I need more of that history.“

| Greenberg's vignettes on the New Haven Police Department feel more like a shrine and less like a complete history. |

It’s a teaching strategy he said he’s working on, but needs the community’s help to improve. In one section, for instance, there are elaborate shelves paying homage to the long history of the New Haven Police Department—including old heroic photographs and a baton that was once in use—close to a sprinkling of history from May Day 1970. Above the shelves, the front plate of a police car winks out from the wall, the glinting hubcap installed where the wheel should be.

It feels like an ode to how New Haven got to community policing, without equal time spent on how it went so wrong. One may find themselves reaching for the the rich afterlives of the Black Panthers, the long fight for a Civilian Review Board, or the current footprint of Black Lives Matter New Haven and People Against Police Brutality.

In another, tucked onto a high shelf in a back room, he has collected a number of glass bottles advertising the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company, an enterprise started and patented by John E. Healy and Charles F. Bigelow—who were white—in the 1880s to sell tinctures, soap and oils marketed as organic cure-alls.

Greenberg’s history is rosy and humorous when he presents it: he discusses the migration of the brand to New Haven in the late 1880s, where Healey and Bigelow hosted traveling “Indian medicine shows.” He shares that they came with mock Native villages (of which he has a grainy black and white photo) and made a career out of it for several years. He laughs at how slippery these two must have been, to market a product that advertised a curative mix of “roots, barks, twigs, leaves, seeds, and berries," according to the New England Historical Society, but was really just molasses and a few extra ingredients.

There’s another way of reading this, of course: the multi-layered exploitation of Indigenous people at a time when Manifest Destiny meant people were losing their land and their lives. In the late nineteenth century, the actual Kickapoo people were forcibly removed from their lands in the American West. It fights the heroism and history of progress that "Lost In New Haven" so often lifts up. But it's part of the history too.

Rubin, who has spent time trying to bridge town and gown in his classes, agreed that collection would benefit for a more robust teaching context. Noting displays on the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, he advocated for an expanded curriculum to which both educators and members of the community could contribute.

“It really is up to people to draw out the history of the city, warts and all,” he said. “It doesn't have to be a heroic story of progress. There are multiple interpretations … it really is our responsibility to raise critical interpretations and read against the material as well.”

“It's not that the collection is there just to accept at face value,” he added. “Each object can be read with the grain and against the grain.”

In a completed and expanded “Lost In New Haven,” Greenberg envisions permanent displays in low light, accompanied by distinct QR codes. He wants to install short, looping video clips explaining each object’s history and provenance, from eBay purchases and architectural fragments to ephemera that friends and complete strangers have brought into his space.

For months, he has expressed interest in the old Bopper’s space downtown on Crown Street, which is still looking for a tenant after both New Haven Center for Performing Arts and Long Wharf Theatre pulled out. He suggested that the city could give him the space for a sort of “made in New Haven” cabinet of curiosities and shop downtown, on which Mayor-elect Justin Elicker has remained mum.

He said he’s also pining after a 21,000 square foot building currently up for sale on Hamilton Street, not far from where the New Haven Clock Factory is being slowly transformed into apartments. The problem: it’s $1.8 million. And the institution he’d like to partner with—the Peabody Museum, which will be wrapped for a three-year renovation—isn’t interested.

As he looks for a new home, he added that he dreams of one day being able to take parts of the museum around the city on a mobile display "kind of like A.C. Gilbert meets P.T. Barnum," designed to fit the needs of a specific audience.

“I want to give the city of New Haven a place where they can celebrate the place they are,” he said. “I’ve taken the huge risk of investing everything I have in this installation. I can’t quit. And I know when I leave here, it’s going to be the big one.”

“We've got to move it,” Clarke said. “We've got to give it the opportunity for artists and people to be animating it. And that's where it's going to amaze people.”

People interested in booking a tour at the current space can contact Greenberg at lostinnewhaven@gmail.com. He also accepts donations through theArts Council for Greater New Haven, which is the fiduciary for the collection.