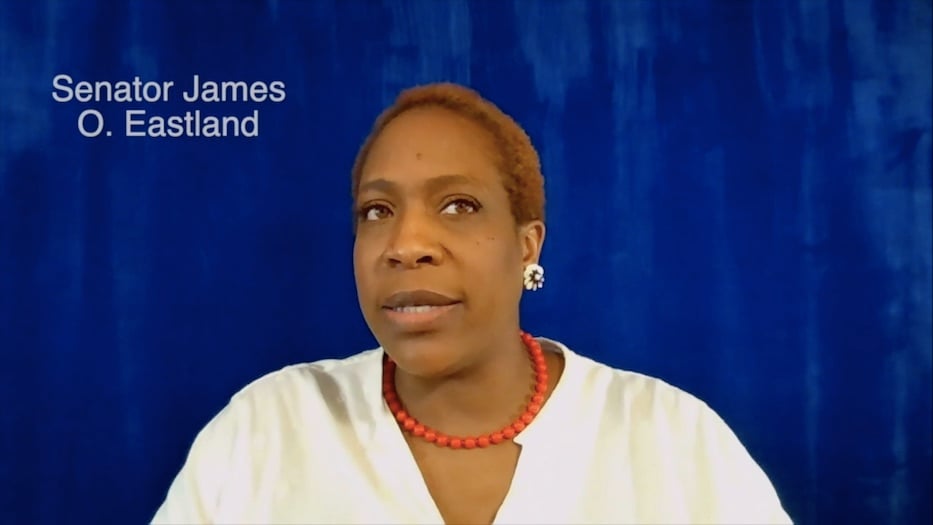

Gracy Brown-Kierstead reading Hamer's testimony. The performance is available online through March 25. All screenshots are from Vimeo.

Fannie Lou Hamer’s words ring out across space and time, bridging decades as actor Gracy Brown-Kierstead brings them to life. On screen, it is August 22, 1964, and Hamer is delivering an appeal before Congress to let her vote safely—which is also an appeal to let her be a full human being. In unflinching detail, she recalls how a trip to register to vote ended in a jail cell, her body beaten as prison guards held her down and commanded two Black men to beat her.

“Is this America?” Hamer asked at the time, in a chronicle of white violence that President Lyndon Johnson tried to have pulled from television. “The land of the free and the home of the brave? Where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily because we want to live as decent human beings in America?”

Hamer’s testimony lives on in Voting: Past, Present, and Future, a multimedia, multigenerational performance running from Collective Consciousness Theatre now through March 25 online. Designed in honor of the 101st anniversary of the 19th Amendment, the performance pairs the recollections of nine elders with the responses of artists working across dance, music, poetry, photography, and painting. It is the timely brainchild of Project Coordinator IfeMichelle Gardin and Director Jenny Nelson.

Elders include Ernie Daniels, Ernestine Davis, Inez Myers, Ellen Pankey, Jacqueline Pheanious, Helena Rodgers, Jean Evans Simmons, Alene Smith, and Margo Taylor. Artists include Jaquanna Ricks, Tahj Galberth, Shari Caldwell-Young, Zoe Jade Phillips, and Sheneta Nicole Walker.

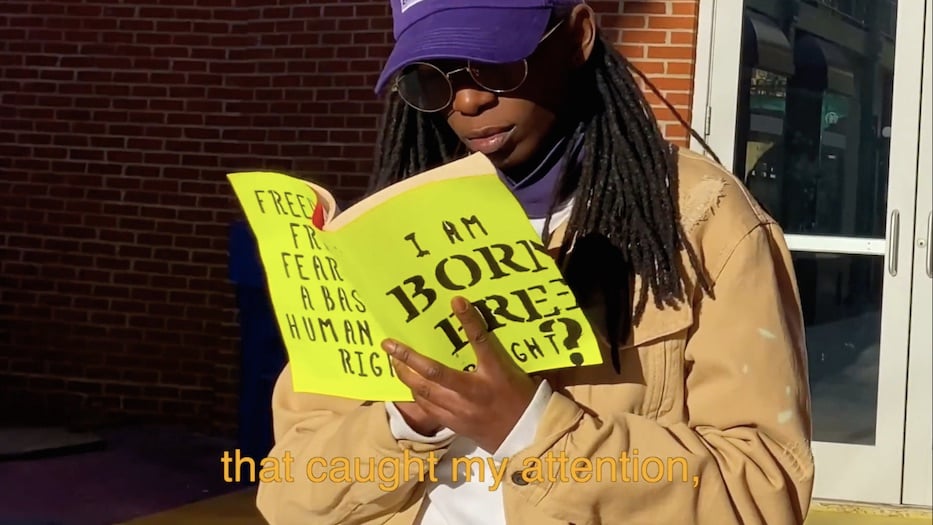

Walker performing in Bridgeport.

From its outset, Voting revels in a sense of intergenerational conversation. Elders’ recorded recollections play in younger artists, meaning that their words are never far from one’s mind. In an early example, words appear in a clean, white script against a black background. In the darkness, a voice declares: “Well, if you don’t vote, you don’t have a voice. And it’s very important that we vote!”

No sooner has she finished the thought than music floods the frame, building from a whisper to a mellow, layered hum. Walker bursts through the double doors of Bridgeport’s Arcade Mall onto a sun-soaked sidewalk outside. Somewhere down the street, a person holds a sign with the words Everybody/Has the Right/To Vote. A second elder’s voice crackles over the image, recalling how she started paying attention to politics after Watergate. Walker starts to sing, weaving through her own history with each verse.

A listener gets multiple layers of her voice at once, interspersed with a conversation Gardin is having with a second elder. The elder says that she has learned to listen to those around her. As if in response, Walker cracks a book open; its cover reads I Am Born Free, Right? Together, these two women speak an argument for voting—and for advocacy—into being.

Artists Jaquanna Ricks and Shari Caldwell-Young.

So too in Ricks and Caldwell-Young’s dance piece, performed across two studios and several generations. As Sweet Honey In The Rock launches into “Ella’s Song” from a speaker set offscreen, the dancers begin to move, navigating a shared choreography in an unshared space. In her home—a setting that feels intimate, as if viewers have been invited in for a cup of tea—Caldwell-Young takes the lead, stepping forward with her whole body.

Ricks dances through the same steps in a studio, her bare feet against the wood floor. As viewers watch them perform the same coordinated, careful movements—an arm arcing toward the sky, a ribcage lifted and lowered just so—the piece becomes meditative. The two mirror each other until there is some creative break, and then respond in a series of individual movements. They dance together but apart, sometimes side-by-side on the same split screen. Their feet, carried by a throaty, muscled call for justice from Sweet Honey In The Rock, do the talking.

Throughout Voting, which packs a punch in just over 30 minutes, those moments of generational cross-talk become a thick, glittering narrative thread. In a segment that includes both poetry and portraiture, Galberth brings viewers into his life in New Haven's Newhallville neighborhood, where he currently lives with his mother and younger brother. For the past several months, he has documented both the neighborhood and those members of his family, weaving a story of why he votes that is as much about who and what he votes for.

Galberth's photographs of his mom and brother are one of the most affecting parts of the performance.

In one of the photos, a teddy bear peeks out from behind a fence, his eyes soft and curious. He becomes a guide to other photographs of the neighborhood: rusted cars parked behind homes, shot from above as if they are dollhouse-sized. Abandoned grocery carts, sidewalk memorials, vans with no owners in sight. Galberth has also taken photographs of his mom and younger brother, their smiles radiating from the screen right into a viewer’s home. The portraits are regal, but intimate enough for a viewer to wonder why this woman’s right to safe housing and affordable healthcare has ever been in question.

“When I’m voting, I’m keeping in mind my family,” he says in between stanzas of a poem that flashes up on the page. “My two sets of photos are really things that I am fighting for, and that I’ve been fighting for. And for me, voting is part of that fight, especially because we as Black people and as queer people have fought to vote. For our ballots to actually matter for so long.”

It is extremely timely: the performance comes amidst white supremacist attacks in Atlanta, wide-ranging voter suppression efforts in Georgia and across the country, restrictions on abortion in Arkansas that may challenge Roe v. Wade, and an insurrection in the U.S. Capitol after which white, violent protesters were treated to organic meals in prison and allowed to leave the country for vacation. There is throughout a call to action—to more fully understand the past as a way to better advocate in the present.

It makes performances like Brown-Kierstead’s feel alive and electric, a collapse of past onto present that is fully intentional. For some listeners, Hamer’s testimony may be new material, despite the fact that she spoke for civil rights at the same time as Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Medgar Evers. During her lifetime, she faced both verbal and physical threats on her life from white nationalists and Southern Democrats, who were often one on the same. Racism was part of her most intimate topography: Hamer was a victim of forced sterilization in 1961, and later was physically harassed for fighting for the right to vote.

It makes performances like Brown-Kierstead’s feel alive and electric, a collapse of past onto present that is fully intentional. For some listeners, Hamer’s testimony may be new material, despite the fact that she spoke for civil rights at the same time as Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Medgar Evers. During her lifetime, she faced both verbal and physical threats on her life from white nationalists and Southern Democrats, who were often one on the same. Racism was part of her most intimate topography: Hamer was a victim of forced sterilization in 1961, and later was physically harassed for fighting for the right to vote.

The inclusion of her words resonates with a second, unspoken presence: the 15th Amendment, which turned 150 years old last year. In 1870, the 15th Amendment ostensibly granted all men the right to vote regardless of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” The inclusion of women, which created a harsh split within feminism, came later. As current history shows, that didn’t mean anything in many parts of the country until almost a century later, when the Voting Rights Act of 1965 became law. The legislation is still thrown into question: voter suppression efforts, particularly against non-white and non-cisgender voters, have never ended.

When Phillips responds to Hamer’s words in a painting, the piece becomes part of a current dialogue on voter rights and legislation. In the painting, Hamer looks determined but exhausted: circles collect beneath her eyes. Hamer is rendered over an engraving from the 1890s that depicts violent voter suppression efforts at the turn of the twentieth century. As Black men tried to register, white men attacked them with deadly and near-deadly force.

“It’s not that far off from what is happening today, with voter suppression,” Phillips says in an accompanying video. “I mean, people aren’t getting murdered in the streets entirely, but there’s all of these laws in action—people shutting down voter registration centers in Black and Brown neighborhoods. Restricting convicted felons from the right to vote. All of these things, like, if you look at them with a critical lens, are essentially the same thing. It’s white men suppressing Black and Brown voices.”

“The power of community and the power of people hearing your voice really can make change,” she continues. “And change history.”

Find out more about Collective Consciousness Theatre here. Voting: Past, Present, Future Voices is available through Thursday March 25. Watch it here.