Music | Arts & Culture | New Haven Free Public Library | Black Lives Matter | COVID-19

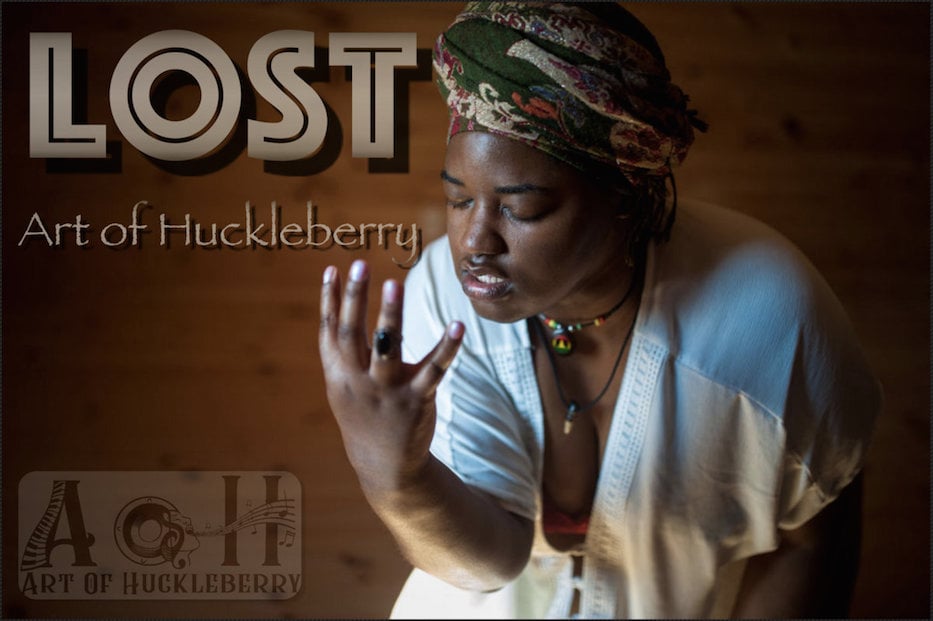

| Cover art for "Lost," produced by Finn Wiggins-Henry and Grant Eagleson in May 2020. Art of Huckleberry Photo. |

A hush. Silence, dim light—relaxed ambiance even in the middle of the afternoon. The soft stroke of finger against key made minor harmonies. Sustained notes wailed a discordant melody. A sultry voice pushed through each chord. The musician’s eyes were closed tight; her face was pained. ALA.NI's "Cherry Blossom" flowed easily from her lips.

And if yo-oo-u see me so-oo-mewhere down that ri-i-i-ver, come a-nd stand beside me-e, it’s alright!

Friday afternoon, Finn Wiggins-Henry sang in the weekend with the latest installment of the “Artrepreneur Series,” a collaboration between the New Haven Free Public Library and entrepreneur-in-residence, musician, and Sopa New Haven founder Eric Rey.

Wiggins-Henry is a jazz musician and the frontwoman of the band Art of Huckleberry, of which Rey is also a member. Previous sessions of the series have included musician Paul Bryant Hudson, muralist Kwadwo Adae and Phat A$tronaut member Chad Browne-Springer. The next session will feature longtime DJ and musician Dooley-O Jackson on Aug. 19.

“On a personal level, I think of Finn as one of the most talented people I certainly have ever worked with,” Rey said. “But Finn is also just such a wonderful spirit. Sometimes, you get to be around people that make you feel all warm and fuzzy inside—that is Finn for me.”

Wiggins-Henry blushed at the comment—when it came down to it, she wasn’t always smooth jazz, a calm aura, and dulcet tones, she said. The road to career, identity, and self-acceptance was marred with adversity and heartache.

Wiggins-Henry was raised by her grandparents in Bridgeport, Conn. From the day she was born, they made sure their granddaughter knew music was in her blood. They fed Wiggins-Henry a diet of gospel, jazz, and blues. It was no surprise to anyone in the family when she picked up the piano. The family was full of musicians—some played piano or guitar, some banged drums, some crooned in clubs, and others sang hymns in church. Musicianship was genetic.

Her biggest inspiration was—and continues to be—her grandfather. Mr. William Wiggins was a country blues guitarist. He gave up his music and picked up a craft to support his family, but that never stopped him from imbuing his first love into Wiggins-Henry. They talked music, listened to music, and played together. Wiggins was always “dad” in her eyes.

“He’s my biggest inspiration because I see so much of myself in him,” Wiggins-Henry said. “My dad is my biggest mascot. I get a lot of inspiration from him, because of his life and what he’s gone through. We’ve even had similar things happen to us—there were problems with my hand at one point. I remember having about 20 percent strength in my left hand and about 30 percent strength in my right. At some point, we both could not play for anything—it was torture trying to play piano for me. His hand stuff is part of why he’s not getting back into it, and it makes me want music even more.”

At school, peers introduced Wiggins-Henry to other forms of Black art and music. It was eye-opening that her people created so many styles. She danced to Afro-Cuban tracks and headbanged to metal. She swayed to R&B and breathed soul in deep. Later in her career, she’d become notorious among her bandmates for the breadth of genres she liked to play at shows.

The industry quashed her drive to explore for some time. She explained that being Black and female meant she needed to work twice as hard as her white peers. It meant shoddy gigs and constant gaslighting. It meant that she needed to bring her own microphone to performances, then her own cable, and, eventually, find access to a sound room. Other musicians had stages set upon their arrival. Wiggins-Henry had to insert herself in spaces that didn’t want her.

The four years between 2013 and 2017 were an angry time for Wiggins-Henry, she said. She wasn’t writing ballads back then. Her music was dubstep and sharp percussion. Her voice was “all rasp and power.”

“A lot of my music came from my emotions,” she said. “I remember singing so much about like ‘fuck men, fuck women, fuck everybody.’ You could hear that pain in my voice.”

At the same time, she went out of her way to take lessons in theory, composition, and technique to improve. Most of her teachers were white, even those that taught her the finer points of jazz. She recalled how they degraded her Blackness in a Black art form. Even more, they made her feel that her gender, again, was a weakness.

Upon reflection, Wiggins-Henry noted that she had felt her most masculine in some of those spaces, itching to be respected by the industry, her teachers, and her peers. Wiggins-Henry’s pronouns were she and they. During that time, a conversation with one of her teachers gave her true pause.

“We were going over all of these beautiful musicians, and I brought up a few women musicians like Alice Coltrane and Nina Simone,” she said. “I remember his specific words were, 'They aren’t important to the history of jazz music.’ I thought, ‘Do you think of me as unimportant?’ I remember him never taking my music seriously and passing me over for certain things. It used to break me down. I thought, ‘What I have to do for myself is just love myself as a Black woman—a Black woman who is a musician. Once I find that love and confidence within myself, I want to start spreading that around for everyone that I know.’”

It was the first time in years that Wiggins-Henry saw herself as a Black woman, she said. She wanted to be a role model for other Black women in the industry and show the world their worth. She described herself as “intrinsically motivated”—confidence meant knowing her value and rejecting gigs that would degrade her. She opened her mind again and sought new art; hip-hop wasn’t all “misogyny and violence,” and femininity didn’t exude weakness. It was a “softer side of herself,” one she grew to like.

That fragility found its place in Wiggins-Henry’s latest single, “Lost.” It’s a track of spoken word, dissonance, echo, and confusion. It’s a passion project that took months to perfect. Instead of forcing inspiration, Wiggins-Henry took things step-by-step. She contacted friends for samples and suggestions and took time to curate each lyric and pitch.

What she put out in the world reflected who Wiggins-Henry was, is, and could be.

If you are still listening somewhere in the near dimension,

Don’t be afraid to return for you are loved!

And that is the key,

To open up your present!

Full of hope! Full of laughter!

Full of love for you and by yo-ou!

“If I could advise my younger self, I would just say something to her quickly, like ‘literally fuck everybody else’s thoughts about you,’” Wiggins-Henry said. “‘Be confident in who you are and know that you are worthy, that you are enough, and that you are great!’ I saw myself always catering to everyone else’s needs growing up. Now, I keep walking in my divine light. I present myself as a free spirit, moving through time.”

The Artrepreneur Series will continue August 19, featuring DJ Dooley-O Jackson. You can register for the installment here.