Arts & Culture | New Haven Symphony Orchestra

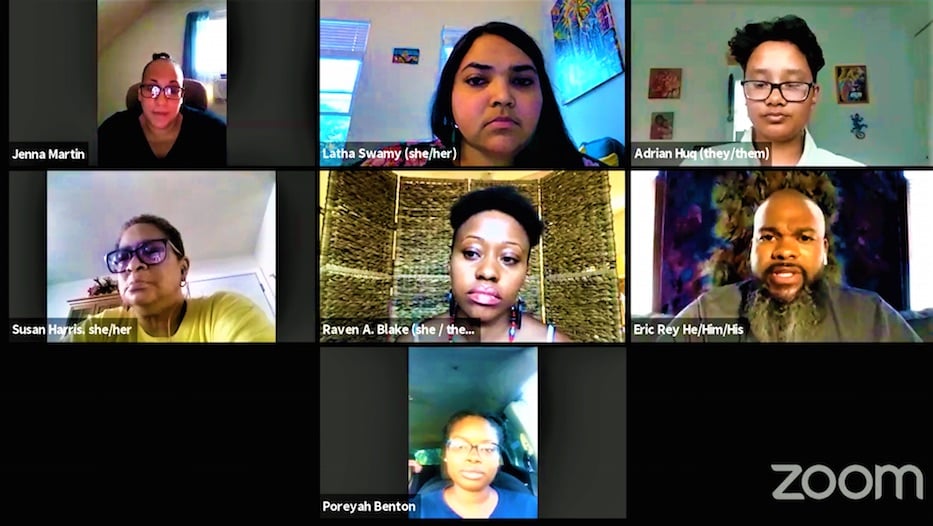

| Screenshot from Zoom. |

Food justice is more than equitable access to healthy meals—it’s an interplay of race, economics, policy, geography, sustainable development, climate change, and a capitalist food system. That dynamic must change before New Haven can call itself food secure.

Wednesday night, eight New Haveners raised those suggestions as they examined food insecurity at a Food Justice Town Hall Symposium, part of this week’s HomeCooked Music Festival from the New Haven Symphony Orchestra (NHSO). The festival brings together virtual musical performances and a call to raise funds for and bring attention to the Community Soup Kitchen, ConnCAT’s Culinary Arts Academy, Haven’s Harvest, and the New Haven Food Policy Council.

Performances have included Anton Kot, the Connecticut Gay Men’s Chorus; Dr. Tiffany R. Jackson; Heritage Chorale Director Jonathan Berryman; Kenneth Joseph of the St. Luke’s Steel Band and others. All of the performances are available here. It comes at a time when emergency food providers have seen need grow by a factor of four since mid-March.

Each member of Wednesday’s symposium represented a different, interlocking sector of New Haven’s food system. Latha Swamy is the director of food policy for the City of New Haven and works closely with the New Haven Food Policy Council. Raven A. Blake is the council’s chair, co-deputy director at CT-CORE, and co-founder and executive director of the Love Fed Initiative. The program promotes food sovereignty in New Haven through agricultural and culinary education. Adrian Huq joined the initiative as a youth member in 2019. Currently, they are an organizer with the New Haven Climate Movement.

Susan Harris is a long-time advocate for food justice in New Haven and served as a Yale Neighbor-in-Residence in 2019. Both Eric Rey and Poreyah Benton joined as owners of the small food businesses Sopa! and Vegan Ahava, both of which began as Collab ventures. Jenna Martin is the head chef and culinary instructor Connecticut Center for Arts and Technology in Science Park (ConnCAT). The panel’s last member was Sade Jean-Jacques; the doula is a cousin to Kina’s Kitchen owner Kaïna Mondesir, a lactation consultant, and founder of Pascal’s Body Care.

“Let’s get this conversation going!” Swamy opened the symposium with a smile. “We’ll start with the first thing that probably is on most of our minds … besides the storm that just came through … the different kind of prolonged storm that’s happening right now is the COVID-19 pandemic. How has the COVID-19 pandemic illuminated areas of advancement for the work that you do in your sector of the food system?”

Harris’ eyes were tender as she chimed in. As a volunteer in New Haven’s food pantries, she’s seen the city’s resilience and generosity firsthand. She described how food providers across the city “rallied together” to provide goods for those in need and how thankful people were to receive them.

Harris explained how the Peer-to-Peer Fundraising initiative (P2P) broke from its brick-and-mortar set-up, partnering with other city entities to set up food deliveries for residents that are elderly and immunosuppressed. Free Summer Meal Programs in the greater New Haven Area have also extended their service until the end of August, meaning children are less likely to go hungry on her watch.

Rey and his brother Alejandro Pabon-Rey became food providers themselves amidst the pandemic. In March, the duo founded Sopa Loves NH. The initiative allowed consumers to donate money for quarts of soup for those in need or anonymously request a quart of soup if they faced food insecurity. What started as a small business initiative boomed as donations flowed. The pair delivered nearly 25 gallons of soup throughout the community and want to continue the program.

“That was great,’ Rey said. “It actually has turned into how we’ll do business moving forward—this is not something that’s specific to COVID, but rather, how we want to do business in the world.”

Blake agreed that there’d been an abundance of resources in the wake of the pandemic, but that surplus also identified vulnerabilities in the food system. She said she wanted to know: Where was that help before? Where would it be after COVID-19?

“That’s amazing, Eric,” Blake started. “The need was met, but for all of these emergency food systems to come to the forefront—how stressed and how crazy it was for these systems to come together rapidly and under pressure really highlighted for me that local and national government-sponsored food programs are not enough,”

“I think folks in a lot of sectors of the food system have known that for a long time,” she added.

Blake recalled her struggles to get funding for many of the initiatives she and her colleagues had proposed before the pandemic. She stressed that the resources a community needs shouldn’t be given only under extenuating circumstances. Instead, food system needs people and institutions committed to steady, incremental development.

Though they were under time constraints, Blake watched community leaders like Harris and Rey provide for their own better and more effectively than those in power did. She’s watched as her own work at CT-CORE and LoveFed made a pivot to mutual aid and food distribution. The food system’s failings placed an unduly burden on the community’s shoulders.

As a climate activist, Huq said they were also frustrated—and afraid. They explained how climate change is deeply intertwined with the food sector; it directly impacts all health and food systems and can wreak havoc on the widespread use of monoculture that American farmers use. Though many citizens are homebound, the world is nowhere near the United Nation’s recommended 7.6 percent decrease in carbon emissions.

Huq added that they see few connecting the food justice movement to environmental justice or climate change. As food insecurity disproportionately affects Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities, neglecting sustainability’s relationship with social justice is another failing.

“Sometimes, the narrative solely focuses around providing food to people,” Swamy said. “When we think about it, it’s a downstream solution. In tandem with social safety nets, we also need to think about policies that are working to address root causes.”

“Instead of pumping money into the emergency food system, we should think about policies that address fair and thriving wages,” she added. “Economic security would allow people to make their own decisions about what they need for their household and would ultimately lead to less reliance on social safety nets, decreasing the need for some of these downstream solutions.”

Martin recalled teaching her students about the industry. They came to her program, wanting to own their own food business. She would soon watch their ambition crushed under a long and grueling road. No cook or chef goes into a restaurant being paid “top dollar,” she said. The food business perpetuates food service workers’ exploitation—meager wages and 15-hour shifts are the only way to make ends meet for most. Martin knew her students would soon sell customers food they couldn’t afford.

Harris pointed to the lack of BIPOC voices in entrepreneurial spaces. Benton and Rey agreed, citing how difficult it was to build their respective eateries with no guidance or set social capital. Benton, for instance, recently taught Rey how to file his restaurant’s insurance.

Jean-Jacques suggested BIPOC “pipeline programs,” spaces where students of color could learn and intern with those that looked like them in entrepreneurial avenues.

“It’s about housing, about access and ownership over land and private property—a whole generational system that often Black, Indigenous, and people of color have been excluded from for hundreds of years since colonization,” Swamy added. “As my work goes, I’m trying to focus on that at the local level, definitely bringing in people from different parts of the food sector to make that actually work. Those policies make sense, work for people, and move toward something that’s community-driven and community-owned. It’s a bit of a multi-pronged approach, but I’m definitely here for that.”

Watch all of the NHSO's videos from the HomeCooked Music Festival here.