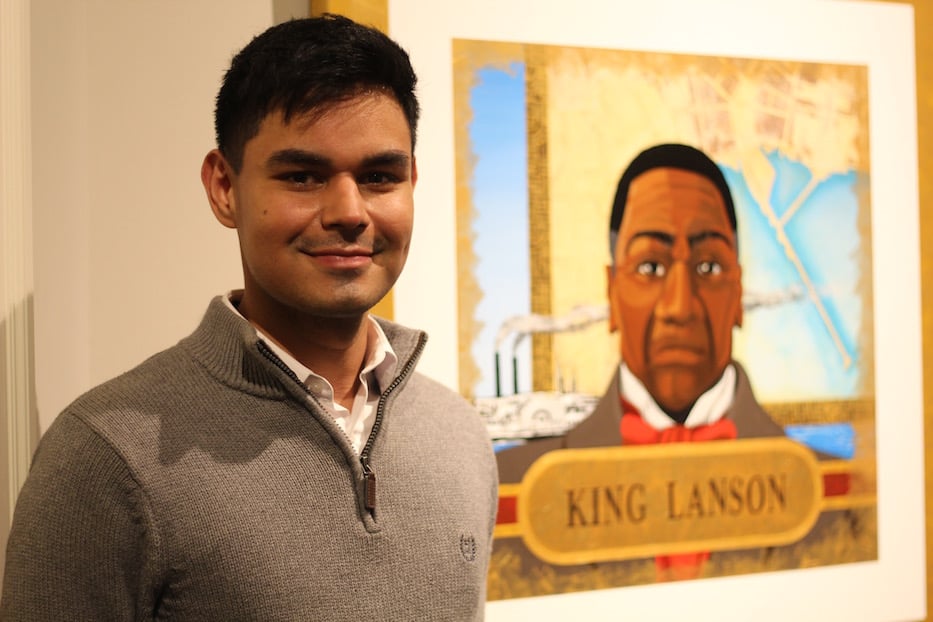

The artist Ricardo Gutiérrez with "King" William Lanson. The portrait will be in the lobby of the New Haven Museum until at least the end of summer. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Mr. Lanson looks right out at the viewer, his eyes wide and studious. There’s something kind there, but also wounded, tired to the bone and still hopeful. Beneath thick, furrowed brows, his lips stop just short of a frown. Behind him, a nineteenth-century blueprint of New Haven rises from the water, a criss-cross of streets and buildings on a weathered map. A steamboat barrels through what might be the horizon line. Enough gold hangs over the sky that it seems the canvas is radiating light.

Artist Ricardo Gutiérrez has brought “King” William Lanson to life in a new portrait, gifted to the New Haven Museum this month in honor of Lanson’s contributions to New Haven. For the artist, whose work builds a bridge from Colombia to New Haven, it is an homage to an oft-forgotten dynamo and a recognition of the shared histories of trauma, displacement, and resilience that live within a diaspora.

It will be on view in the museum’s lobby through at least the end of the summer. Gutiérrez is quick to say that it is inspired by Dana King’s sculpture of Lanson, which she unveiled on the Farmington Canal Heritage Trail in September 2020. Read more about that here and here.

“I think New Haven deserves to have a portrait of William Lanson,” he said in a recent interview at the museum. “It's so nice that New Haven wants to keep his legacy alive and I'm so happy and honored to contribute with something.”

Gutiérrez’ interest in Lanson began last year, after Site Projects Director Laura Clarke reached out to him following his exhibition Urabá. At the time, Site Projects was working towards a potential mural project in New Haven’s Hill neighborhood, on the old Hill Cooperative Youth Services building at the corner of Salem and Carlisle Streets. After seeing Gutiérrez’ “delicate touch,” Clarke asked him if he would be interested in joining as a commissioned artist.

She explained that the project is part of a wider effort to honor Lanson’s life and work, including a 2020 mural on Crown Street from Uruguayan artist David de la Mano. When she told him the story of Lanson—the Black genius who built the city’s Long Wharf, advocated for abolition and Black suffrage, was responsible for sections of the Farmington Canal, envisioned an integrated neighborhood around Wooster Square, and then died in an almshouse—Gutiérrez was floored.

“He did a lot for this life and for New Haven,” Gutiérrez said. “The way that he finished his life, I don't think it was fair. It's very sad that we cannot go back in time to correct all the injustices that William Lanson endured, but it's nice that we can keep his legacy alive.”

The more he learned, the more he felt compelled to paint Lanson back into the historical record. Gutiérrez dedicates much of his work to the story of Indigenous Colombians and Afro Colombians, from the country’s abolition of slavery in the nineteenth century to the present. When he read that Lanson’s life ended in relative obscurity, something in him broke. Lanson died in 1851, the same year that Colombia formally abolished slavery. Gutiérrez thought about Palenque, Colombia, which he describes in an accompanying label as “the first ‘free town’ in all of the Americas.”

The more he learned, the more he felt compelled to paint Lanson back into the historical record. Gutiérrez dedicates much of his work to the story of Indigenous Colombians and Afro Colombians, from the country’s abolition of slavery in the nineteenth century to the present. When he read that Lanson’s life ended in relative obscurity, something in him broke. Lanson died in 1851, the same year that Colombia formally abolished slavery. Gutiérrez thought about Palenque, Colombia, which he describes in an accompanying label as “the first ‘free town’ in all of the Americas.”

He just had one problem—there are no known renderings of Lanson from his lifetime. The sculpture, which King based on historical research from the time period, was the closest thing he could find to an image.

“And then I realized—wait a minute,” Gutiérrez said with a little laugh. “I’m an artist. I can make him. I can paint him.”

Before starting on the canvas, he visited King’s sculpture, studying Lanson’s eyes, his knitted brows, thick, stately bowtie and the way sunlight fell over his forehead. The artist marveled at his close-cropped hair and cutaway tailcoat, which glows on bright New Haven days. He took note of the single scar above Lanson’s right eye, which he carried into his portrait. King has called the scar a symbol of “the physical danger that he was in, and the emotional danger that he encountered every day.”

Gutiérrez took visual note of every detail, and snapped photos for reference. Then he headed back to his home studio in the city’s Edgewood neighborhood and got to work.

In the finished rendering, Lanson’s gaze is direct and immediate, quick to engage a viewer. A red bow tie blooms beneath his square chin, bright as a poppy. Behind him, J. W. Barber’s 1831 map of New Haven traces the city out to the Long Wharf, where a thin strip of land extends into the Long Island Sound. There’s that signature, uninterrupted and shocking blue of the New Haven sky, which the artist experienced for the first time while visiting the city in 2016. In case there’s any confusion around who this is, text on the work reads King Lanson.

Gutiérrez has incorporated one of his signature molas, a nod to the ornate, bright and tightly woven textiles for which the Indigenous Gunadule people along the Gulf of Urabá are known. He has also painted a gold frame and signature, to leave “a little bit of Ricardo” in the piece.

It feels fitting in the lobby of the museum, which was born as the New Haven Colony Historical Society in 1862 and still houses an archives and records room on the first floor. The building’s home at 114 Whitney Ave. is less than two miles from the city’s Long Wharf, where Lanson left his most enduring and transformative footprint in 1810. If a viewer wants to, they can walk from the portrait to King’s seven-foot sculpture in roughly 10 minutes. In a sense, Mr. Lanson is home.

Mary Christ, collections manager at the New Haven Museum, said that she’s thrilled to have the portrait in the museum’s collection. In Gutiérrez, both she and Executive Director Margaret Anne Tockarshewsky see an artist who has balanced all of Lanson’s life—the very bitter and the very sweet—in a single work. While Gutiérrez acknowledges Lanson’s trauma, “I think the first thing anyone notices is just how visually striking it is and how beautiful it is,” Christ said. The work ultimately feels celebratory, triumphant.

Christ added that the painting, currently installed in the museum’s lobby, will be a valuable teaching tool for hundreds of future visitors. Roughly four years ago, she and colleagues thought about how they wanted to picture Lanson in the museum’s maritime collection. Since late 2020, they’ve had an image of King’s sculpture. Now, they have one more way to teach people about his work in the city.

The New Haven Museum is open Wednesday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday noon to 5 p.m. Learn more at its website.