Dixwell | Arts & Culture | New Haven Free Public Library | Black Lives Matter | COVID-19

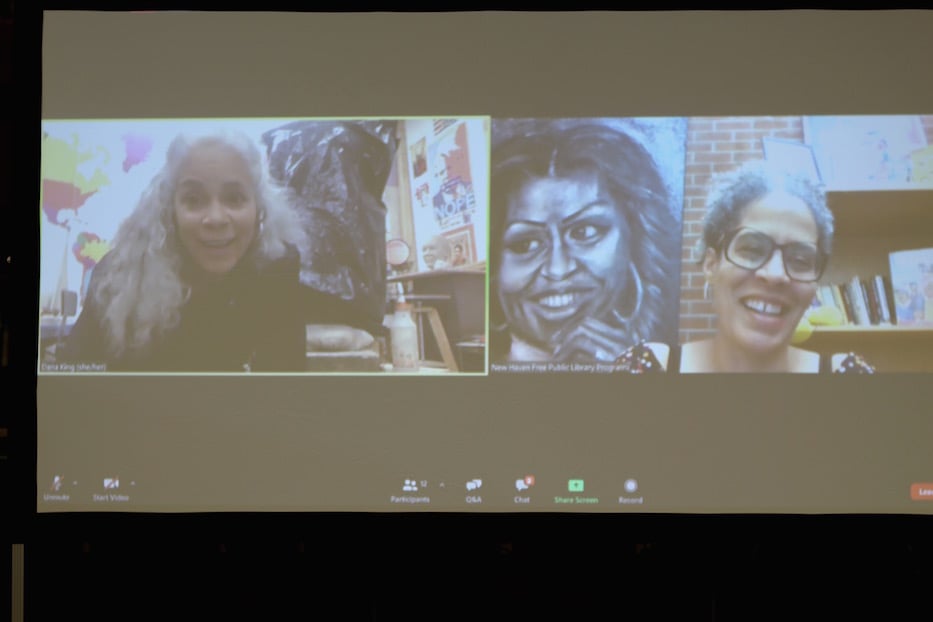

| Sculptor Dana King and Artspace New Haven Executive Director Lisa Dent. Lucy Gellman Photos. |

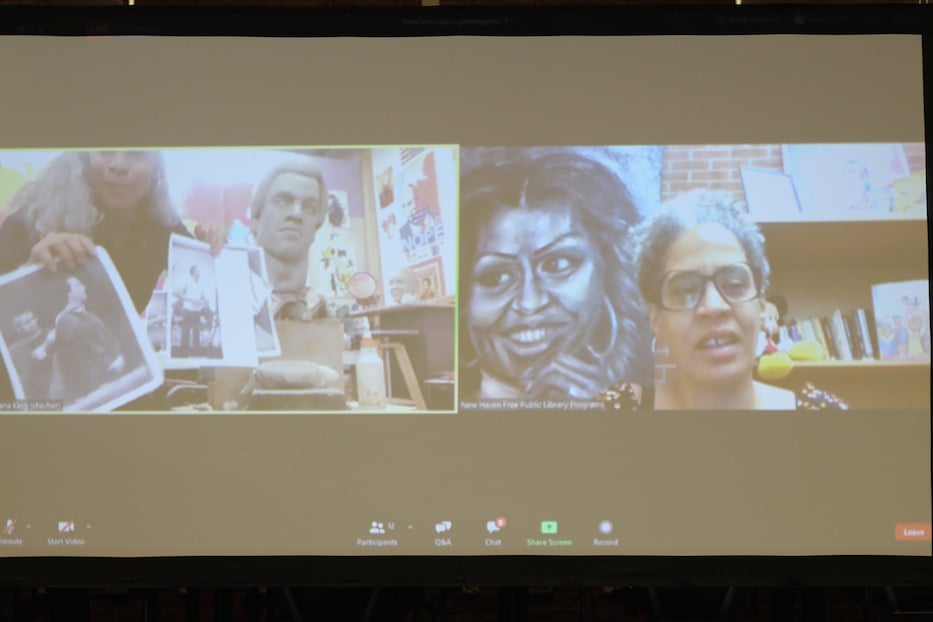

William Lanson’s eyes blazed momentarily from behind sculptor Dana King, piercing but kind. Around her, an Oakland studio shifted into focus, still intact under a recently orange sky. In another one-inch box, Artspace New Haven Director Lisa Dent sat up in her seat, a smile teasing at the edges of her mouth. A portrait of Michelle Obama beamed behind her.

Across New Haven, over 100 fourth graders and their teachers watched transfixed, connected through a network of cable and chromebooks that bridged New Haven and Oakland. Their questions popped up one by one in a chat box as their faces remained off screen.

Wednesday morning, King appeared virtually at Stetson Library to speak on her seven-foot bronze of William Lanson, the Black engineer who built New Haven’s Long Wharf, sections of the Farmington Canal Heritage Trail, and developments in the Wooster Square neighborhood during the nineteenth century. The sculpture, which was commissioned by the Amistad Committee, will be unveiled at the mouth of the trail on Sept. 26. King arrives in New Haven on Monday.

The conversation was organized by Stetson Library Branch Manager Diane Brown in collaboration with Dent and Cultural Affairs Director Adriane Jefferson. It was intended to reach fourth grade students across the city, who are in their third week of remote learning due to COVID-19.

| Stetson Branch Manager Diane Brown and City Librarian John Jessen. |

“It was important to me to have New Haven Public Schools kids participate in this,” Brown said as she prepared for the event, doing a final check on socially distanced chairs and Zoom sound quality. “I think too many times, we have these events in the community, and no one thinks about the children. They get left out. This sculpture, it’s gonna be right here in the village. I call Dixwell the village. It’s a Black history lesson.”

The pandemic has changed the way Stetson does programming, from virtual “Africa Is Me” classes each month to online story time with librarian Phillip Modeen. When Brown was organizing the event, she sent a Zoom link out to the entire New Haven Public Schools district, with the hope that young people would be able to join. She also called on a village of Black women to tell Lanson’s story.

Both Brown and Jefferson have spoken out about the need for greater diversity in the city’s cultural scene. King has championed larger-than-life “Black bodies in bronze” as both a reclamation and reminder that Black hands built America and then were selectively written out of its artistic, economic, and legal history. Dent, who began her tenure at Artspace in May, arrived at the gallery just in time for an exhibition exploring the Black Panther Party 50 years after May Day. Last week, she welcomed lifelong activists Ericka Huggins and Angela Davis to Artspace through Zoom.

“I’m just really excited for this monumental event,” Jefferson said as she took a podium, looking out as if there were hundreds of school kids waiting eagerly before her, instead of nine mostly-empty chairs. “What we’re seeing is an unveiling of this deep cultural history. We actually have a Black woman who sculpted William Lanson. So today, I hope that you are all inspired. I hope you leave feeling like you know more about your history.”

| Adriane Jefferson: "What we’re seeing is an unveiling of this deep cultural history." |

As King told the story of Lanson’s life, work, and legacy in New Haven, a parallel narrative emerged—that of Black women holding each other up and spreading the gospel of lifelong learning. King charted her own journey to sculpture, which began when she was just a kid, doodling on whatever she could find around the house.

“I’ve been an artist my whole life. My whole life,” she said. But “I didn’t know that you could be an artist.”

As a student, she was often reprimanded for being too loud and energetic in the classroom (“Every report card said, ‘Dana talks too much,’” she recalled). She put those skills to use in broadcast journalism, working for decades as a reporter and news anchor. Her work took her across the globe, including a reporting trip to Kosovo during which she found herself painting a series of portraits of Muslim women. She was never taught Black history as part of her formal education; much of that knowledge came later, from her own research.

When she was 48, she started art school while still working full-time. Wednesday, she laughed recalling how frenzied her days were—she would study painting in the morning, and then snap back into broadcast journalism mode in the afternoon, dirty hands and all. A master class in sculpture turned her on to the medium a decade ago. She still gets a jolt of energy every time she opens a 25-pound bag of fresh clay.

“It’s a belief that this work needs to be out in the world,” she said Wednesday. “My goal has always been for young people to say, ‘That looks like my aunt!’ Or, ‘That looks like my dad, or my uncle.’”

Along the way, she’s moved through that mission with the support of other Black women. She praised Thelma Harris, who founded an eponymously named art gallery in the Bay Area, for taking a chance on her work. She noted that the artist Mildred Howard was the one to bring up her name when a committee was looking for a sculptor to commemorate California legislator William Byron Rumford. It became her first public sculpture.

“We’re good with that, Black women,” Dent said. Around her, Stetson seemed to silently agree: the library is filled with charcoal and oil canvases by Katro Storm, celebrating Black history as it flows from past to present. A huge mural of T'Challa sits on the building’s back wall. Even thinned out, the shelves boast stories filled with young Black protagonists.

King nodded, her long white hair spilling over one shoulder. Howard was hard on her, she said. But “she taught me everything.”

The sculpture of Rumford helped her establish herself. In 2018, King unveiled her sculpture Guided By Justice at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. The piece, which depicts three women cast in bronze, is both an homage to the woman who guided the Montgomery Bus Boycott and to the matriarchs in her own family. The sculptor later learned about the Lanson commission through author Regina Mason, a friend who also happens to be the great-great-great granddaughter of the fugitive slave William Grimes.

Through the commission, King fell “in love with him,” she recalled. She read about the little-known Black genius who allowed New Haven to compete with the port of New York, as he cut and loaded the stone for the city’s Long Wharf. She learned about Lanson’s work on the Farmington Canal, where the statue will soon stand with a patina that glints in the sun.

In her research, she saw how Lanson used his life to advocate for both free and enslaved Black people, at a time when there were only about 800 free Black people living in the city. He helped lay the groundwork for Temple Street Church, which would later become the Dixwell Avenue Congregational Church of Christ. The building now stands on Dixwell Avenue, just a two minute walk from the library’s front door.

She also watched the arc of history betray him, as white, wealthier city residents took away his land, his wealth, and his power through a series of false allegations and harassment from the police. Lanson died in a poor house in 1851, just three years after the state formally ended slavery and 26 years after the last sale of slaves on the New Haven Green.

“His is a man who was a Christian a believer, and they harmed him,” she said. “But he still maintained his dignity and his strength.”

| Dana King Photos. |

In response to both Dent’s questions and a number of Edgewood School teachers who wrote in, King spoke at length about her process making the sculpture (read more about that here), which began in her home studio. When she started her research, she could only find documentation that Lanson was 200 pounds. There were no photographs of the man who had built so much of the city. She “decided to make him a powerful 200 pounds,” she said.

As she sculpted his face, she drew on faces of nineteenth-century West Africans, placing a scar above his right eye. She dressed him in neat clothes beneath which a viewer can still see his muscles. She made him “look sharp,” she said—because she couldn’t imagine him any other way.

And there was “my protest,” she added. On his leg, his hand is curled in a fist. If he could raise it, it would become the universally recognized symbol of Black power. King completed the gesture earlier this year, as marchers called for justice for George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and other victims of state-sanctioned violence in Oakland and across the U.S.

“I feel like he would have been with us at this time,” she said, calling him the through line from the late eighteenth century through the mid-nineteenth, and on to the twenty-first. “He needs to be there. He needs to be back in New Haven.”

King added that she is excited to visit the place where Lanson’s legacy still exists in the built environment; that "space is power," and she feels right about the sculptor coming home. She praised Mayor Justin Elicker for a tentative plan to apologize to Lanson. In an interview earlier this year, Elicker said that it pains him to know how wrongly Lanson was treated by the city and the community.

“That’s huge,” she said. “That’s what this country needs to do. And that’s huge. It’s time for the United States to apologize for slavery. And for Jim Crow. And for systemic racism. And for police brutality. That can start with New Haven.”

The work doesn’t ever stop, she added. In Oakland, she has begun work on a bust of Huey Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party with Bobby Seale. Fredrika Newton, Huey's widow, has helped guide her process. She and Dent traded factoids about the party, which started on the West Coast and had a strong chapter in New Haven.

Back in the library, Brown looked over a Zoom-to-classroom setup more reflective of New Haven than the very schools from which teachers were writing. In the city’s public schools, 72.5 percent of teachers identify as white, to only 12.9 percent of students. As the discussion wound down, Dent asked King what advice she would give to them as they navigate this year.

“I would say that we all have a gift,” she said. “And it may take some time to reveal itself. And that’s okay. Things come as they come. Don’t be hard on yourself.”

“The thing I would be really happy about,” she added, “is you’re learning this history.”