Economic Development | Arts & Culture | Theater | COVID-19

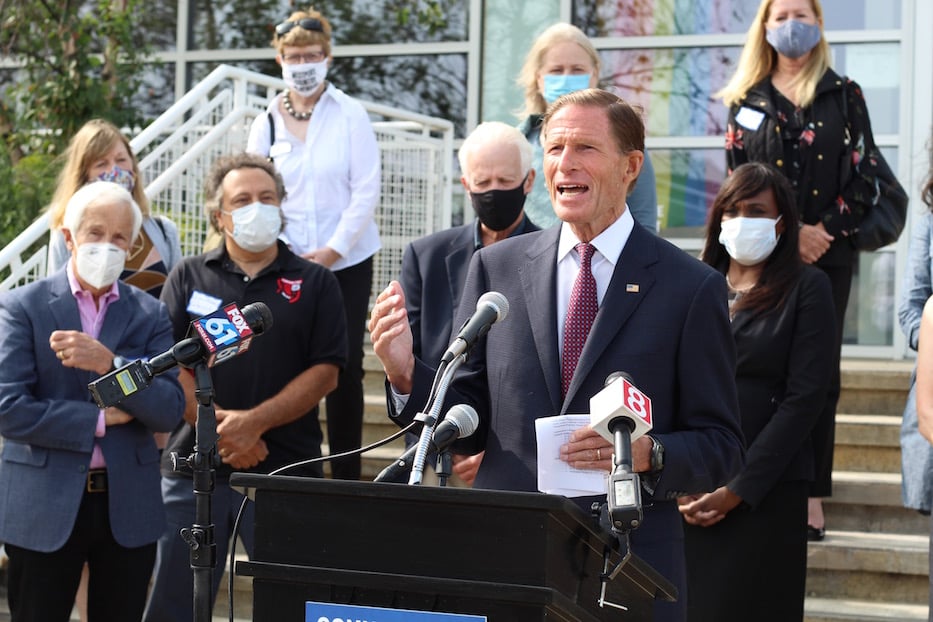

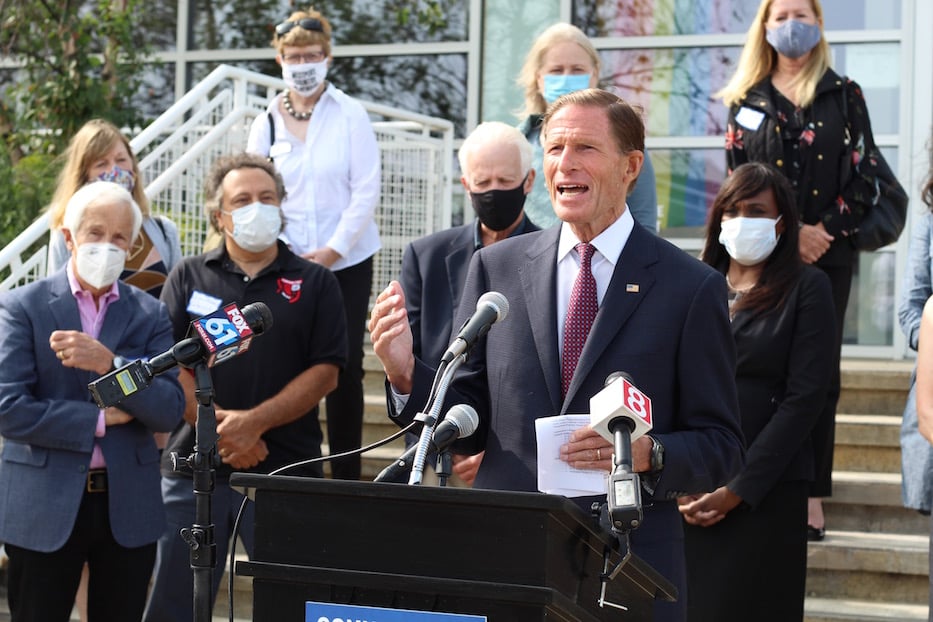

| U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal, who described the theaters as "in the fight for the cultural soul of our nation." |

Six Connecticut theaters have lost $12 million in revenue and laid off over 150 people during the COVID-19 pandemic. Now they’re calling on the federal government to help keep them afloat.

That plea brought U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal to the steps of Long Wharf Theatre Monday morning, as he spoke in favor of the Save Our Stages Act and a push to get $12 million in CARES Act Funding to Connecticut’s six flagship producing theaters. Those theaters include Long Wharf Theatre, Goodspeed Musicals, Hartford Stage, the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center, Westport Country Playhouse, and the Yale Repertory Theatre.

It follows a request for economic aid that the theaters made to Gov. Ned Lamont in July. Earlier this year, the state received $1.3 billion in federal CARES Act funding, $75 million of which now lives in the Connecticut Municipal Coronavirus Relief Fund Program. Of the overall funding, the six theaters are asking for $2 million each, or a total of $12 million.

"It is a matter of survival," Blumenthal said. "Not convenience. Not luxury. It is a matter of survival."

The Save Our Stages Act would allow the U.S Small Business Administration (SBA) to make grants of up to $12 million to eligible performing arts venues and operators, such as theaters and concert halls. It would also allow the SBA to re-grant additional funding to those institutions at 50 percent of the original amount. It was initially introduced by U.S. Sen. John Cornyn, a Texas Republican, and U.S. Sen. Amy Klobuchar, a Minnesota Democrat, in late July.

Since its initial proposal, over three dozen cosponsors have signed onto the bill from both sides of the political aisle. Blumenthal is also advocating for the Restart Act, which would extend Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) funding. Neither can proceed without a vote.

“Connecticut is blessed with a rich array of performing arts and theater,” he said as dramatic gusts of wind rolled off the Long Island Sound, bringing in a momentary chill that felt like an Ibsen play. “We ought to treasure that they are, in fact, gems. National treasures. To risk their demise is utterly irresponsible.”

Monday, both Blumenthal and artistic staff pointed to the arts as a significant economic driver in the state. Prior to the pandemic, Connecticut’s six producing theaters accounted for over $40 million in revenue and 1,700 jobs, including contract and seasonal positions. Arts, culture and tourism accounted for $800 million in state revenue, according to 2017 data from Americans for the Arts. For each dollar spent, institutions reported an $8 return on investment.

| Long Wharf Theatre Managing Director Kit Ingui. |

But theaters have operated on thin margins for a long time, meaning that lost performances can add up very quickly. When COVID-19 hit the state in March, closures left postponed performances, cancelled seasons, and fledgling virtual programming in their wake.

Long Wharf, which had just announced its 2020-2021 season, suddenly found itself without the final two performances of the year. Hartford Stage postponed its season, then cancelled it. The Yale Repertory Theatre, which was 48 hours away from previews of A Raisin In The Sun, announced a cancelled season, followed by a year with no theater to cover the costs of students taking a fourth MFA year. Florie Seery, associate dean at the Yale School of Drama, said classes have been going smoothly for two weeks, as stages remain strangely quiet.

Since March, the six theaters have lost a cumulative $12 million and laid off over 150 staff members, with more losses estimated before the end of the year. While most have pivoted to virtual programming, new play development, and online summer camps, almost all of it has been free—meaning that the theaters are desperately in need of cash flow. Across Connecticut, the sector has lost an estimated $386 million and over 33,000 full- and part-time jobs, according to the Connecticut Arts Alliance.

Monday, those stories seemed to repeat themselves over and over. Kit Ingui, the managing director at Long Wharf, said the theater ended the fiscal year with an estimated $2 million loss from the 2019-2020 season, and a “complicated year” ahead (it is poised to announce its 2020-2021 season virtually on Wednesday). After an initial round of layoffs in the spring, it eliminated 40 full- and part-time positions, bringing a staff of 65 to 25. Those do not include hundreds of contract workers—actors, directors, dramaturgs, educators, artistic fellows and designers—who usually fill the theater each year.

| U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal and Michael Price, director emeritus at Goodspeed. |

While the theater qualified for and utilized first-round PPP funding, that money has since dried up. In June, the National Endowment for the Arts also named Long Wharf as one of nine CARES Act Funding recipients in the state, for which the theater received a one-time amount of $50,000. That money, too, is gone.

“Our six theaters are currently appealing to the state for $12 million as an essential investment in our economic redevelopment due to COVID-19,” she said Monday. “But that is only the beginning of our industry’s needs. We all want to bring people, artists, and staff back to work to create the art and tell the stories that can help repair the damage our human infrastructure has suffered since March.”

Todd Brandt, interim director of marketing at Hartford Stage, said that it has been a devastating year of losses for the theater. Last fall, Hartford Stage opened its season with champagne toasts and new programming to celebrate Artistic Director Melia Bensussen’s first season. Now the theater is estimating $1.4 million in losses, with more to come next year.

It has cut its Fiscal Year 2021 budget from $9 million to $3.5 million. At the beginning of the pandemic, it had 80 staff members, and an additional 120 contract workers. It is now down to just 21.

“It’s all terrible,” he said. “That’s why we’re here. Our goal is to put people back to work. We want people in our theaters, we want people on our stages, and we want people backstage.”

“Reimagining The Arts”

| Adriane Jefferson: "It is our duty to use the arts to start to talk about these issues and see how the arts can play a role in activating change in how we deal with crisis." |

Monday, artistic and cultural leaders also pushed beyond an economic argument, reminding attendees that the arts, at their best, can be part of the fight for social justice and racial equity. Adriane Jefferson, director of cultural affairs for the City of New Haven, noted that theater makers don’t only have the power to change hearts and minds, but also legislation on the state and federal level.

Since joining the city in February, she’s worked to do that on a municipal level, and urged attendees at Long Wharf to do the same. In particular, she encouraged arts leaders and theater makers to center BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) artists and Black joy in their work going forward.

“The City of New Haven is very special,” she said. “We are the hub of arts and culture in the state of Connecticut. I like to refer to us as the heartbeat. We are the talent. We are the innovators. We are the cultivators of what drives arts and culture in this state.”

But if theaters can’t keep their lights on or pay their employees, those artists can’t do their work. While praising the Save Our Stages Act, she pointed to the racial and socioeconomic stratification that the COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare, particularly in majority-Black and Latinx cities like New Haven. She referenced the work that she and city officials have done on artist relief funding, an evolving cultural equity plan and new arts for anti-racism pledge that seeks to hold whiter, wealthier institutions and nonprofits accountable.

“We’re in unique times, and we all know this,” she said. “We’ve been in crisis mode since March. With the pandemic. With racial injustice all across our nation. And it is our duty to use the arts to start to talk about these issues and see how the arts can play a role in activating change in how we deal with crisis. I think right now, what we’re doing here is reimagining the arts. Not only in the city, not only in the state, but in the nation.”

| Nancy Alexander: “In any society, it’s the artists, it’s the creators who draw attention to injustice and help create the solutions. When theaters are shut down, some of those voices are shut down.” |

Nancy Alexander, who sits on the board of Long Wharf Theatre, added that she sees theater as a pathway to empathy and cross-cultural understanding. Earlier this year, Long Wharf was among several regional theaters to announce its commitment to anti-racism work, an approach with which Artistic Director Jacob Padrón has been leading the organization since his arrival in 2018.

“In any society, it’s the artists, it’s the creators who draw attention to injustice and help create the solutions,” she said. “When theaters are shut down, some of those voices are shut down.”

Asked if the Save Our Stages Act has a demonstrated commitment to racial equity—most of Connecticut’s theaters are still run by white people, with overwhelmingly white board representation—Blumenthal pointed to community partnership programs at many of the theaters. Several of the programs, which cover everything from free childcare to student talkbacks and theater workshops to compensating local artists, have been temporarily discontinued in the midst of COVID-19.

“I don’t think there’s one size fits all approach for the number of board members that are minority or not,” he said in a conversation after the press conference. “I think that the purpose of this funding is essential survival.”

“On The Razor’s Edge”

| Michael Price and John Fisher. Fisher is the outgoing director at the Shubert Theatre. |

Blumenthal said he feels optimistic around the Save Our Stages Act, particularly as it gains bipartisan support from his colleagues. Since advocating for the act in Stamford last week, the senator has seen 10 more colleagues sign on as cosponsors. He urged Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to push the bill towards a vote.

He added that there is a “need” based component to the Restart Act, and acknowledged that many small and specifically women-, Black- and BIPOC-owned businesses were locked out of the Paycheck Protection Program and emergency disaster relief funding. As he spoke, he explained that he sees the two bills as deeply intertwined: the Restart Act throws an economic life preserver to many of the restaurants and small businesses that people dine and shop at when they see theater or attend concerts.

That economic boost can’t come fast enough, he added. In Washington, Dr. Anthony Fauci has said that it may be over a year until audiences can be in indoor theater spaces without masks. Michael Barker, managing director at Westport Country Playhouse, said that the theaters won’t survive that long without a lifeline.

“All of these organizations, all of the Connecticut Producing Flagship Theaters, we are here because we were able to avail ourselves of PPP,” he said. “Our employees that we had to furlough and lay off are alive and fed and in their homes, because of the enhancement on unemployment. We are now on the razor’s edge of a dire, dire situation.”

From a staffing perspective, that has translated to slashed positions, tiny marketing and artistic departments, and long hours for the staff members that remain. At Goodspeed, 57 staff members have become 24, with another 172 contract workers unaccounted for. At Westport Country Playhouse, 12 people are left from an initial 32. Hartford Stage has lost 59 people; the O’Neill has lost seven full-time staff, and an additional 80 seasonal staff. The Yale Repertory Theatre has retained its 50 full-time staff members, but lost an estimated 60 guest artists. It is the only producing theater attached to a university with a $30 billion endowment, and has still reported a $592,400 loss.

Monday, Ingui said that restoring some of the staff positions would be a priority for Long Wharf the theater if it is to receive more funding. But, she added, COVID-19 has created a sort of mountain—the theater would have to make significant coronavirus-safe updates to its spaces before letting audiences in.

Even if they do, audiences aren’t particularly eager to return. A recent survey that Long Wharf sent out indicated that there was overwhelming concern around public health. In the meantime, the theater has implemented temperature checks and contact tracing for remaining staff.

“We don’t believe patrons will be coming back anytime soon,” she said. “They have been pretty clear to us. So we believe we are in for emptiness for a while inside our spaces.”