Arts & Culture | Elicker Administration | COVID-19 | Arts & Anti-racism

| Together New Haven. |

Arts organizations across New Haven have said that they’re ready to do anti-racism work. Now, the city is holding them to it.

That’s the idea behind a new arts for antiracism pledge that the city’ Division of Arts, Culture, and Tourism is rolling out this week, as part of the ongoing Together New Haven campaign. The pledge, which challenges arts organizations to think beyond diversity in the abstract, is the brainchild of Cultural Affairs Director Adriane Jefferson and summer interns Sean Roach and Maryam Hajialigol.

Roach comes to the division through the state’s Arts Workforce Initiative program; Hajialigol is a Yale Presidential Fellow. The two have also been in virtual anti-racism training sessions as part of their summer work.

“When we’re addressing diversity, equity, and inclusion, we’re also talking about justice,” Jefferson said during a recent meeting of the city’s Cultural Affairs Commission. She later added that “it's about doing transformational work for everybody.”

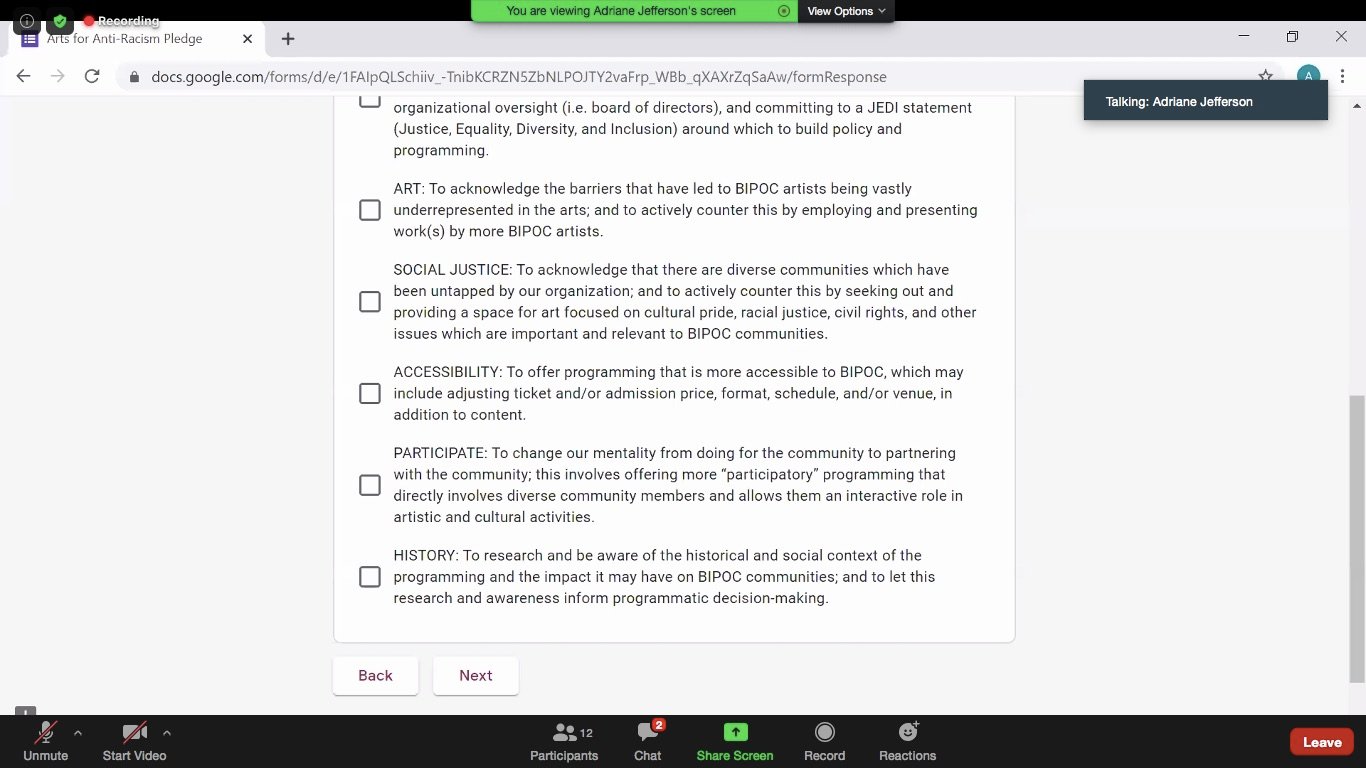

| A meeting of the Cultural Affairs Commission in early August, during which members got a peek at the new pledge and toolkit. Screenshot from Zoom. |

It follows over a dozen statements from local arts organizations earlier this summer, all of which vowed to combat racism after the state-sanctioned murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May. Very few of the organizations used the terms “anti-Black racism,” “police brutality,” or “white supremacy;” few also outlined specific policy and personnel changes they were planning to make.

Only two, the International Festival of Arts & Ideas and Long Wharf Theatre, have held programming to address police brutality and the normalized murders of Black transgender women.

The pledge is a continuation of the anti-racism work Jefferson was doing before she arrived in New Haven. During her time at the Connecticut Office of the Arts, she instituted the R.E.A.D.I. (Relevance, Equity, Access, Diversity and Inclusion) framework; prior to that she worked with young writers of color at The Writer’s Block, InK in New London. Since February, she has been working towards New Haven’s first-ever cultural equity plan. When COVID-19 hit the city in March, she began working on Together New Haven with the city’s Economic Development Administration, under which the division now lives.

The new initiative is meant to address a concern she noticed from both city arts organizations and municipal arts leaders across the country, with whom she is in a working group through Americans for the Arts. Around her, she heard artists and arts organizations saying they were genuinely interested in doing anti-racism work—and ready to do it—but didn’t have a template. Some were already immersed in that work; others vowed anti-racism with largely white leadership and nebulous language. Jefferson said she sees the pledge as a way to both help organizations and hold them accountable.

“I was inspired by a lot of the conversations I was having with the other municipalities, and realizing that people didn't have any direction,” she said in a phone call Monday morning. “The complaint I was hearing was that people wanted to do the work, and they needed a pathway. This is the pathway.”

The finished document, which lives on the Together New Haven hub, consists of a virtual pledge, an outline of anti-racism commitments, and an online toolkit of resources from the Cultural New Deal to lists of living Black composers, playwrights, and authors. Before organizations sign on, the division has asked them to consider their own internal workplace culture, policy and practice, and commitment to anti-racism programming in their work and willingness to collaborate with the New Haven community.

The pledge also includes a challenge to think about and combat the historical and contemporary barriers to BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color) artists that organizations have put up in the past, in everything from grant applications to hiring practices. Once they’ve signed, organizations are placed in a cohort with regional partners that have also vowed to do the work. Jefferson then plans to check in on them to see what they need—and whether they are following through.

The website also includes an interactive calendar, with events that range from online anti bias, anti-racism training sessions to Zoom roundtable discussions on the arts and Democracy. Upcoming events include a webinar on envisioning higher education in the arts, a national educator anti-racism conference, and discussion on racism hosted by the Akron Minority Council. The staff is working on adding a greater number of local events.

“We all have to do this collectively,” Jefferson said. “For us, there’s an accountability level too. Everyone has this opportunity.”

After showing the pledge to members of the commission last week, Jefferson said she is excited to roll it out to the city. Barbara Schaffer, a cultural commissioner who is also the director of development for Elm Shakespeare Company, noted that the resource bank will be especially helpful for her.

As a member of an organization that is predominantly white, Schaffer said that Elm Shakespeare has been having “a lot of these conversations” in the past two months, as it reckons with its own role in structural racism. While Elm Shakespeare hires teaching artists of color, works with kids of color, and has focused on providing financial relief during COVID-19, the organization's leadership and staff is almost exclusively composed of white women.

“This is such a toolkit,” she said. “It’s so fantastic. Thank you.”

Lindy Lee-Gold, a senior specialist with the Connecticut Department of Economic and Community Development, praised the initiative and asked Jefferson what she could do to get the word out to local institutions. Calling in from the road, she nodded intently as Jefferson went through the pledge section by section, including a page of questions on action items that organizations are planning to take.

If there is a time for anti-racism work in the arts, “the opportunity is now,” she said.

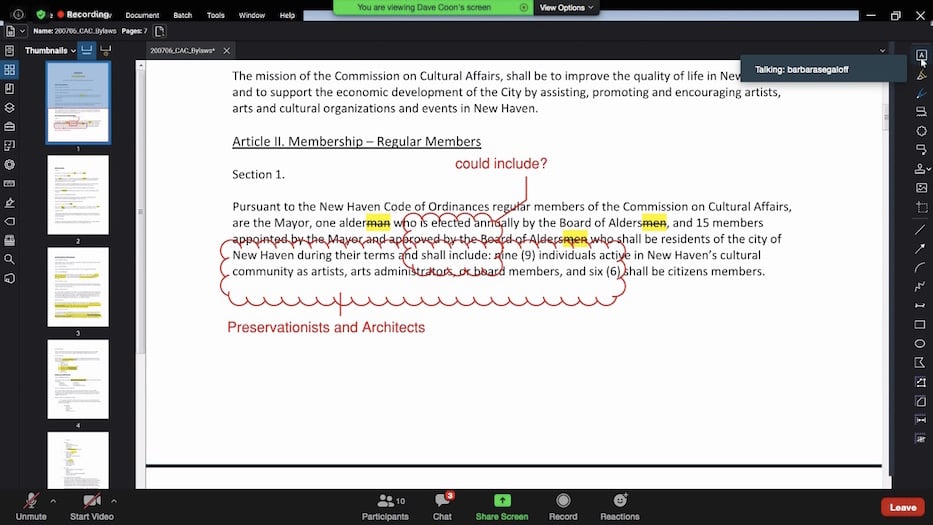

The pledge comes as the Cultural Affairs Commission updates its own bylaws to reflect more inclusive language around sex and gender, race, and the profession of commissioners invited to serve. Currently, commissioners are majority white, while the city’s population is roughly one-third white, one-third Black, and one-third Latinx. Architect David Coon, a commissioner and associate with Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects, is leading the effort on the revisions.

“I think we can be ahead of the curve on this,” he laughed when Lee-Gold pointed out that the Board of Alders is still referred to as “aldermen” in some city documents.

The commission has not yet said anything about geography, or the intention of its majority-white members to step down when their three-year terms end in June 2021 and June 2022. Members, almost all of whom were tapped by former arts czar Andy Wolf, are largely concentrated in the city’s Westville, East Rock and Wooster Square neighborhoods (one member each lives in Newhallville and West River; the commission's aldermanic appointment is Dwight Alder Frank Douglass). There is currently no representation from the Fair Haven, Hill, Dixwell or Whalley/Edgewood/Beaver Hills neighborhoods.

Find out more about the pledge here.