LGBTQ | Long Wharf Theatre | Arts & Culture | Theater | Black Lives Matter | COVID-19

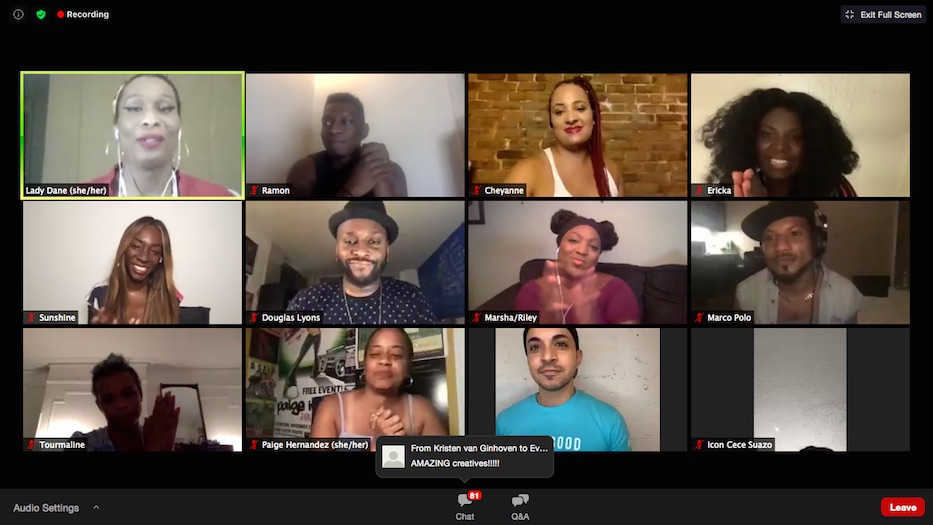

| Members of the cast and crew after the final performance, Cece Suazo's YOU WILL NEVAAA ENTER OUR HIGH HOLY LAND OF BLACKNESS (HIYA). Screenshots from Zoom. |

Marsha P. Johnson boards a train into New York City. It's June 1969, heat rolling through the station. Passers-by are ruthless: they jeer as she speeds for the platform. The scene shifts. A young couple is on a date the night of the 2016 election, whole worlds unfolding between them. It shifts again. A trans Black woman is trying to defend herself in New York, as she’s assaulted at gunpoint while waiting for the city bus. It shifts a third time. Three friends are reminiscing about the neighborhood, before gentrifiers moved in and a well-loved playground disappeared.

Those stories landed at Long Wharf Theatre virtually Wednesday night, as part of “Black Trans Women At The Center: An Evening Of Short Plays.” The one-night event included work written by Dezi Bing, Cece Suazo and Douglas Lyons and directed by Tourmaline, Lady Dane Figueroa Edidi, and Paige Hernandez. It was hosted on Zoom and included a talkback among Lady Dane Figueroa Edidi and Suazo, moderated by longtime New Haven activist Bubbles.

Joey Reyes, executive assistant and line producer at the theater, noted that Long Wharf plans to share a recording of the evening with those who registered for the event but lost power due to Hurricane Isaias.

“Long Wharf Theatre is on a boundary-breaking journey of centering the works of those that have been historically underserved and underrepresented,” they said.

The performance dovetails with the theater’s evolving pledge to decenter whiteness and white supremacy on its stages and in its practices. Following the state-sanctioned murder of George Floyd in May, the theater released a statement doubling down on its commitment to anti-racism work. In June, it released Sing Their Names, a commission with Steven Sapp and Mildred Ruiz-Sapp of UNIVERSES. Wednesday, Reyes called the performance a continuation of that vow.

| Clockwise, from top: Lady Dane Figueroa Edidi, Bubblicious or Bubbles, Joey Reyes. |

It is timely, if not long overdue: in New Haven and across the U.S., protests have increasingly pointed to the need for greater intersectionality in the Black Lives Matter movement, including an acknowledgement of the queer and trans Black women at its forefront. During a youth-led protest on the Fourth of July, organizers took time to say and honor the names of murdered Black trans women as they marched through the streets of downtown New Haven.

Even on a screen, that message came across Wednesday night. As they waited before a black background with block lettering in blue, white, and pink—colors that have become synonymous with transgender visibility—audience members began to buzz with excitement, the pandemic-era equivalent of raucous pre-show chatter.

Several placed party hats, peremptory applause, many-colored hearts and fire emojis in the chat box. Others fired off quick words of encouragement to the artistic team. It felt like a reunion: many of the attendees have not seen each other for months, as theaters remain closed and work dries up or moves online.

“So looking forward to this! This lineup of artists is incredible,” commented Samuel Morreale.

“Y’all better WERQ!” added Alan Sharpe.

| Clockwise, from top: L Morgan Lee, Tourmaline and Samy Nour Figaredo in Dezi Bing's Things Unknown. |

And from that first breath, actors, directors and producers did. In Dezi Bing’s Things Unknown, the audience jumps between the first night of the Stonewall Riots in New York City to the city’s recent past. In one world, Johnson is boarding a train to New York, fighting off the threats of onlookers. In another, it is Nov. 8, 2016, as a young couple discusses one partner’s HIV positive diagnosis amidst the noise of Donald Trump’s impending victory.

The parallel is propulsive and tight: two trans Black women separated by nearly five decades of history (both played by a nuanced, revelatory and at times gut-wrenching L Morgan Lee), both just trying to live.

Bing writes nimbly through history, interested in the people and moments that live in its interstitial spaces. Instead of watching Marsha P. Johnson (a fast-talking, wildly charismatic Lee) in the thick of the Stonewall riot, the audience watches the night that led up to the riot, from the legacy of steel-spined Black women in Johnson’s family to the box in which society attempts to place her. The audience can feel the pressure building, even as an imaginary bead of sweat rolls slowly down Lee’s face and she pays it no mind.

Bing jumps ahead, and Samuel (Samy Nour Figaredo) and Riley (Lee, equally ebullient but more pensive) find themselves on an election night date, trading witticisms that soon give way to vastly different histories. In under 15 minutes, the playwright juggles colonialism, stigma, and layers of normalized oppression without ever having to use the words. Instead, she folds them into the sharp comebacks, the hurt and knowing reserve etched on Riley’s face, the gradual cave of Samuel’s mouth before he walks away, eyes wet.

Buttressed between two historical events—one that pushed gay liberation forward but also whitewashed its history, and one that has attempted at every turn to roll it back—Bing deftly shows how much is tied to the sinking, mind-numbing weight of white supremacy. For any audience member still under the illusion that history is a forward march toward justice, she tears off the bandage, and shows it instead as a scratched record that keeps going even as gravel gets stuck in its grooves.

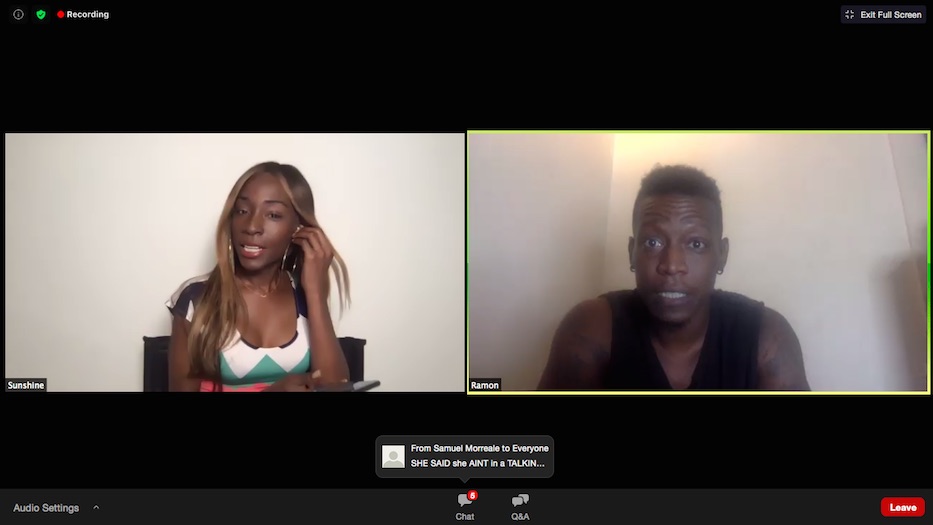

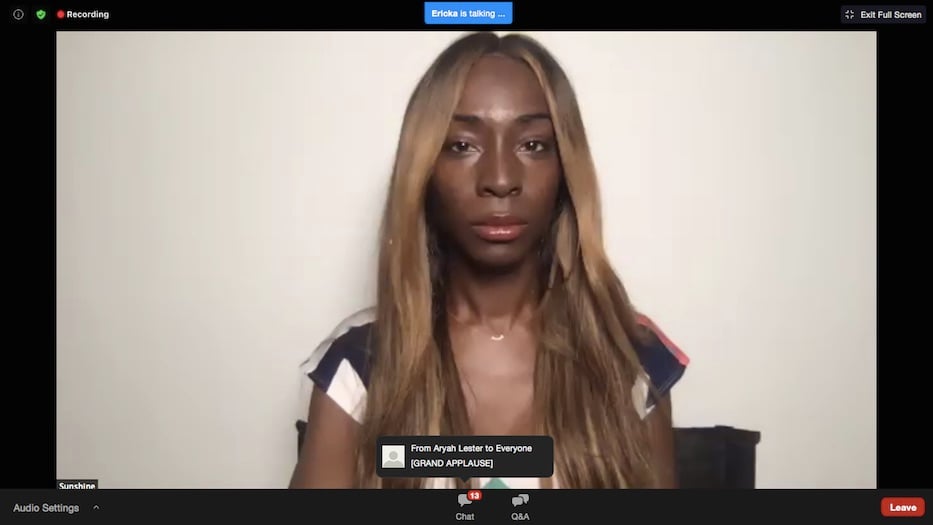

| Angelica Ross as Sunshine and Martin Bats Bradford as Ramon in Douglas Lyons' Sunshine. |

Wednesday, the work found itself in dialogue with Douglas Lyons’ Sunshine, which follows the titular character Sunshine (a stunning Angelica Ross) as she is followed, harassed, and threatened at gunpoint while waiting for the bus home. Her perceived fault: trying to live her life as a Black trans woman who wants to be left alone as she waits.

Like Bing, Lyons dives deep into inherent bias, othering, and stigma—as well as toxic masculinity—writing them all into his character Ramon (Martin Bats Bradford) and the quiet, willful complicity of the city as it moves around Sunshine, aware of her plight but unwilling to help. A narrator Ericka (Joaquina Kalukango), doubles as the show’s one-woman chorus.

As the play began Wednesday, Kalukango soaked it in Lyons’ knack for the lyrical, introducing Sunshine with poetic, righteous anger that billowed up around her. Through a box on a screen, Ross brought Sunshine’s world into crisp focus: the city block where she waited, the phone call with a friend, the way even dancing can become an act of transgression for a Black woman, let alone one facing both misogynoir and transphobia.

Lyons’ setup hit at the solar plexus: the setting could be an audience member’s street in the present. Maybe it was: it became nearly impossible not to watch the play with bated breath and a sick, knowing feeling. Sunshine, who is robbed of due process because of who she is, is familiar enough to be a neighbor, sister, aunt, confidant. Audience members came to her defense in all-caps letters and notes of “this is so relatable” that felt like ripples through a live, electric house.

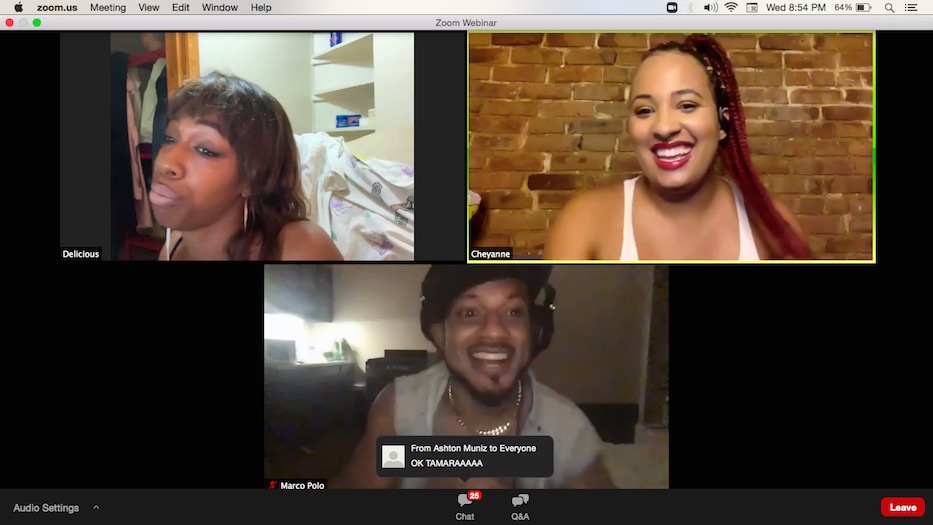

The play’s aftershocks flowed into Suazo’s YOU WILL NEVAAA ENTER OUR HIGH HOLY LAND OF BLACKNESS (HIYA), in which Cheyanne (Ianne Fields Stewart), Delicious (Tamara M. Williams) and Marco (Jaime Cepero) mourn the very real loss of their neighborhood—and of Delicious’ Black trans sisters—as the space rapidly gentrifies around them.

In the play, the three cover an enormous amount of ground: the carceral state, the demonization of poverty, the Jack and Jills gentrifiers who take, and take, and take, because they always have. But conversation is never forced: it feels organic with a side of elegy, like a semicolon rather than a period.

“I call it 11 signs the neighborhood will never be the same again,” Delicious says at one point, and one can see signs for “Chapel West” popping up in the city’s Dwight neighborhood, or Zumba studios and artisan cheese shops edging out generations of families in Bed-Stuy.

At another, she notes that she’s been to 15 funerals in two years, and it is enough to bring an audience member to their knees, a reminder of why they've gathered in this space. Suazo binds the words with song, a bird loosed from Stewart’s throat more than once in under 20 minutes.

“I think that in 2020, we are being invited into a new way of existence,” Lady Dane Figueroa Edidi said at the end of the night, in a talkback with Bubbles. “All of us as humans. And I think that what we’re being asked to do is really to dismantle internalized white supremacy and systematic white supremacy.”

| Clockwise, from top: Tamara M. Williams as Delicious, Ianne Fields Stewart as Cheyanne and Jaime Cepero as Marco in Cece Suazo's YOU WILL NEVAAA ENTER OUR HIGH HOLY LAND OF BLACKNESS (HIYA). |

“Part of the obstacles that we face in our community is the blatant erasure, the taking of our analysis, economic praxis and our way of doing things,” she added. “Everyone’s saying mutual aid, mutual aid, mutual aid, mutual aid. Everybody’s talking about mutual aid. But … the principles of mutual aid, the foundation of that, are within Indigenous cultures. And Black and Brown trans people were practicing cooperative economics and mutual aid because that was a way for us to survive.”

Her comments were a mirror on the night: the format allowed three plays to work as moving, interlocking parts of a greater whole. Playwrights made it clear: Black trans lives, and Black trans women, cannot matter in a vacuum (or, for that matter, a single reading or evening of plays). They must matter all the time, in every fiber of the Black Lives Matter movement and the language and embodiment of Black liberation.

Or, in the words of Lyons' character Ericka: “All Black Lives matter, just in case you never knew. Now I wanna hear from you: what are you gonna do?”

During the talkback, Suazo spoke about the difference she has experienced as a Black trans woman living between Los Angeles and New York City, the first of which has stricter civil rights legislation. She reminded audience members that artistry can be a radical act, if it champions true representation and equity work.

“What Dane and I are both doing is activism work,” she said. “We don’t have to be, you know, getting chained and locked up. We don’t have to be in front of the lines. As long as we’re doing this, we’re showing visibility in the performing sector.”

Long Wharf Theatre is on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. To find out more about Long Wharf's upcoming season, click here. To visit the theater's website, click here.