Dixwell | Jazz | Music | Arts & Culture | New Haven Free Public Library | Arts & Anti-racism | Shubert Theatre | Monk Youth Jazz

Top: Clifton (Cliff) McClean and Bob Turek. Bottom: Doron Monk Flake. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Doron Monk Flake wiped away a steady stream of tears and listened to a soft carpet of piano rolling across the floor. Moments before, high school freshman Alijah Steed had channeled Sam Cooke, and taken Stetson Library to church in the process. Flake looked out over four generations of jazz lovers, from months-old vocalists still in their strollers to retired educators ready to dance. He started to cry into the mic as the lyrics to US3’s “Cantaloop (Flip Fantasia)” waited patiently in front of him.

“I’m just so happy to know—” he paused to take a deep breath as the tears kept coming, and he beamed at Steed. “Whew! That this music is in good hands.”

It was one of several candid, intergenerational, and explosively joyful moments Saturday afternoon, as Monk Youth Jazz, the Shubert Theatre, newly-opened Stetson Branch of the New Haven Free Public Library and members of the band Chill came together for a celebration of jazz on Dixwell Avenue, once the city’s main jazz corridor. Over 60 attended the event, the first public concert at the new library. By the end of the afternoon, it felt like a mellifluous christening of the space.

“Jazz is America’s music,” said Marcella Monk Flake, founder and executive director of Monk Youth Jazz, as parents and kids filed into the second floor of the library. She motioned to the band behind her, noting how their instruments came together to make a single work of art. “We are all part of this wonderful, wonderful experiment called democracy.”

The collaboration has been, in some ways, a year in the making. Last March, Shubert Executive Director Anthony McDonald began his tenure at the downtown theater with a vision for community, from more diverse board leadership to simply showing up at neighborhood events. In the months since, he’s made an effort to book programming that looks more like New Haven, including the Dance Theater of Harlem last fall and jazz pianist Monty Alexander on April 2.

When Kelly Wuzzardo, director of education and engagement at the Shubert, saw that Alexander’s 2019 Wareika Hill Rastamonk Vibrations was a tribute to the late Thelonius Monk—whose legacy lives on vibrantly in New Haven—a lightbulb went off in her head. Both Stetson and Monk Youth Jazz are community partners of the theater; Wuzzardo herself spent years doing events at Stetson’s former home across Dixwell Avenue. She picked up the phone and called Marcella Monk Flake, who set up the band and the activities. Stetson Branch Manager Diane Brown, who has brought music into the library for years, said she was thrilled to host.

“As a new person in this community, I’m learning every day more and more about the history, and especially the jazz aspect of this history,” McDonald said. Both he and Wuzzardo added that it is a teaser of sorts for his inaugural season, which will likely see more of New Haven’s artists on the Shubert’s College Street stage.

Top: Marcella Monk Flake, who called jazz "a different kind of intelligence" in an interview after the performance. Bottom: The audience gets into the performance.

From the very beginning of the afternoon, both Flake and the band centered the long tradition of experimentation, close listening, individual and collective voice work and yielding the floor that builds the backbone of jazz music. Taking the mic to introduce herself, Flake took the audience back in time to jazz' birth in the call-and-response of work songs, which became a language of survival for enslaved Black people. She traced its evolution into an art form that weaves through funk, folk, gospel, rap, R&B, fusion, and the music of the African, Afro-Caribbean, and Afro-Cuban diasporas.

“Jazz is complex, and you can articulate it in a few words,” she said. She pointed to members of the band behind her, who often practice in her living room with her husband, the pianist Dudley Flake. Between them were generations of jazz history, reaching from New Haven church bands to long-gone venues that used to populate Dixwell and Newhallville. Each had a story of the music that had hooked them in childhood—playing percussion with pencils and palms on classroom equipment, a single James Brown record that opened whole universes, years in the marching band at James Hillhouse High School.

Together, Flake said, they create a mirror for the best version of democracy. When they play together, jazz musicians listen to each other and elect a temporary “leader,” whose chance to solo gives him control of the floor. “When he’s the leader, he’s like the president of the United States,” she said. And then, when a musician senses that he’s said enough with his instrument, he yields the floor to another voice, and steps back to support it. As she spoke, dozens of pairs of eyes looked back, absorbed in each word.

Nowhere was that clearer than in the playing itself, which jumped from Ella Fitzgerald, James Brown, Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn to Sting and US3. As members of the band introduced themselves, Flake handed out sheets of blue crepe paper, turning the audience into a wave of electric color. Inviting young listeners up to the front, she began to sing the first two lines of “Blue Skies,” bobbing her head as Clifton (Cliff) McClean traded his saxophone for a flute. She asked listeners to lift their sheets of paper in time with the music.

Suddenly, an off-the-cuff comment from drummer Pete Hines—"whatever y’all do, just play from the heart”—seemed more like a directive. At Flake’s first suggestion of Bluuuueeee skies/Smiling at me, her vocals dipped in honey, the room became a sea of blue, arms undulating across the space. When some flapped up and down against the rhythm, Flake urged people to listen more closely. Behind her, the instruments were having an unhurried, Sunday afternoon kind of conversation.

To McClean’s burst of flute, Dudley Flake laid down a pillowy piano riff, Bob Turek’s bass and Roy Alexander’s bongos gentle on the entrance. On drums, Hines waited for a downbeat, and then surprised people with a tap-tap-tap of cymbals. When Flake sang Nothing but blue skiiiesss/Do I see, it was convincing enough to banish a sudden rainstorm outside. “You almost got it! Let’s do it one more time!” she cried between verses. “Awesome!”

“Jazz is like gospel in a lot of ways,” she told attendees. “You don’t just sit and watch. It’s not for spectators. You have to get involved.”

Top: Cliff McClean on sax, Ashleigh, Doron, Marcella and Makeda Monk Flake on vocals. Bottom: Nisaa Williams performs.

That excitement flowed through performances from Nisaa Williams, Alijah Steed and Doron Monk Flake, as listeners jumped in to fill in lyrics, responded with cheers and applause, and ultimately stood to dance along. “Sing it! Sing it!” someone shouted as Steed launched into the first verse of Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come,” and wailed the lyrics with a wisdom well beyond his years. Listening carefully for an entry, McClean and Randy Bost threaded their way into the third verse, adding brassy, full-lunged bursts of saxophone and trumpet.

When Flake soared from Cooke to US3, he took a minute to loosen up at the mic, letting his shoulders and knees ease into the music as the lyrics dipped in and out of the instruments. Underneath the words, Bob Turek laid a thrumming, bouncing bass line that felt like a lane Flake could ride all the way from oral tradition to jazz fusion to the cradle of hip hop, drenched in poetry and spoken word.

Just two minutes in, he stepped away from the mic, letting the trumpet do all the talking. Lifting his horn high in the air, Bost made the instrument growl and then climb, its voice steely at the edges. As Bost turned toward the rest of the band, members who had toned it down came back in. “Yeah! Yeah!” Flake responded as the instruments swelled. “Biddy biddy bop/Funky funky.”

“You hear that rhythm and that rap?” Bost said as Flake left the stage. “Yeah! That's just like playing history, man. Playin’ jazz riffs. Singin’ jazz riffs.”

Everywhere, there were reminders of the tenderness and ebullience with which jazz is handed down. When Williams sailed through “A-Tisket A-Tasket,” piano and soft percussion rolling behind her, the whole front row was ready to jump in with the call-and-response that builds the song’s climax (“Was it green?” attendees bellowed. “No no no nooooo!” Williams crooned back).

When Doron Monk Flake pulled up lyrics to “Cantaloop” before singing, a tiny voice from the back of the audience chimed in with “One minute!” and became part of a performance flecked with both laughter and tears. When Marcella Monk Flake stood to sing gospel jazz with her adult children Doron, Ashleigh and Makeda, Bost told attendees the story of how she had lost her voice for months, and it returned to her in what felt like a miracle.

A mix of funk and jazz standards kept the audience responding to the music. When the band flowed right into Duke Ellington’s “Satin Doll,” McClean and Dudley Flake watched each other closely, figuring out the moment for McClean’s entrance in a language of wide eyes, long looks and small nods. As soon as McClean took the floor, he laid out decades of jazz history, making the sax roar, growl, and wail as a soprano sax and flute sat ready at his feet.

“We know where to go, and you don’t have that too often,” McClean said. Moments later, he had picked the sax back up, and was having a musical conversation with Hines and guitarist Frederic Herbert. They didn’t need to speak a single word to get the point across.

“That Made Me Feel Brave”

.jpg?width=933&name=ShubertStetsonMonkJazzCollab%20-%201%20(1).jpg)

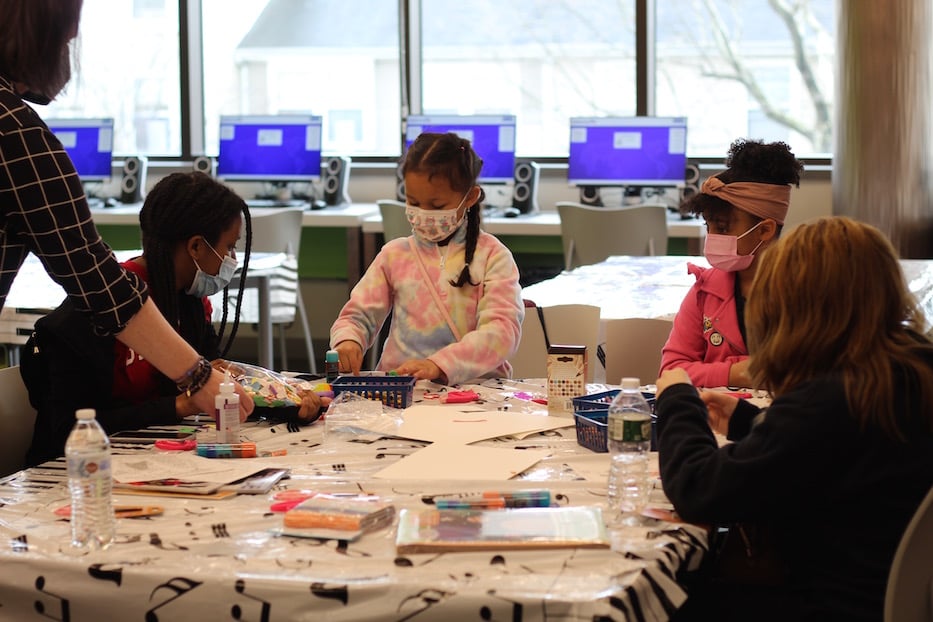

At a neat cluster of tables, a few young listeners let the music float over them as they designed mixed media collages. Williams, who is seven, said that jazz makes her feel “happy,” whether she’s performing it or listening. Just minutes before, she had delighted the audience with a performance of Ella Fitzgerald’s “A-Tisket, A-Tasket,” taken from the nursery rhyme of the same name.

While she was born into it—she is Marcella Monk Flake’s great-niece, and a member of Monk Youth Jazz—she’s also fallen in love with the art form. When she sings smooth jazz, it helps her calm herself, she said. When she sings a standard, “it makes me feel thrilled.” Saturday, she’d had butterflies at the beginning of the song, but eased into it with the reminder that her family was there, surrounding her in music from every direction.

“I felt a little nervous, but also very excited,” she said. “The thing I did was I mainly looked at my mom. That made me feel confident and that made me feel brave.”

Beside her, 7-year-old Leah Berberena designed a hanging collage with her name in bright, colorful foam letters. Back in the audience, her 71-year-old grandmother listened to the music. Magdaliz Gonzalez, who is in a relationship with Berberena’s dad, bounced between the music and the crafting tables to check in on both of them. She praised the library as a space that had enough programming to delight both of them, and said she’s be back.

Back at the carpet-turned-stage, Marcella Monk Flake asked the band to play the afternoon out. On Dixwell Avenue, drops of hail had started to fall, the wind so fierce that they blew sideways. Inside. Bost pulled out the warmth of Louis Armstrong’s “It’s A Wonderful World.”

“In spite of everything that’s going on, it is a wonderful world,” he said. Without prompting, McClean’s buttery saxophone came in under him. Piano and bass entered in lockstep with each other, giving guitar time to tiptoe in. On the drums, Hines listened for an opening, and played in time with Alexander’s gentle touch on the bongos. The song ultimately belonged to Bost and McClean, who have played together and individually for years.

“Music can take you anywhere,” Bost had said earlier in the afternoon, and the words hung in the air. “Anywhere.”

Monty Alexander will perform at the Shubert Theatre on Saturday, April 2. Tickets and more information are available here.