Arts & Culture | Artspace New Haven | Unidad Latina en Acción | Visual Arts

| Objects from Día de Muertos are up at Artspace New Haven through Nov. 24. |

She is impossible not to see when you catch her at the opening of a wall, bathed in pink light. A crown of red flowers rests on her head, pulsing with color. Fluttering, orange-winged butterflies sprout from her eye sockets; snakes slither across the bone white of her cheeks and forehead. Her arms, two strong branches, sprout from her sides with autumn leaves at the shoulders. A toucan sits on her shoulder, looking out over the space. You can almost hear a warning escape from his beak.

Pedro López and Silvana Deigan’s Mother Earth is one of hundreds of skeletons, brightly decorated skulls, forward-lurching freight trains and ornate kites populating Artspace New Haven this week, for a special exhibition on New Haven’s annual Día de Muertos parade and celebration. The exhibition is a collaboration among Artspace and members of Unidad Latina en Acción (ULA), particularly ULA artist-in-residence Pedro López.

After opening with an artist’s talk and reception Saturday night, the exhibition has a short run through Sunday Nov. 24, when it will end with an anti-deportation training for allies. It marks the last event of City-Wide Open Studios, during which López was one of 13 special commissioned artists.

López, who hails from Guatemala, is a member of the Cerbataneros Sumpango, an arts collective that specializes in huge, vibrant kites (barriletes gigantes) to celebrate the dead. For three months each year, he travels to New Haven to help with preparation for the Día de Muertos festival. The kites bring a millennia-old tradition to New Haven, channeling the 3,000 year old practice that connects the living to their ancestors on Nov. 1.

“Death and life are very much close together,” he said Saturday, speaking through translator Rosario Caicedo. “There’s a unity there. There’s no fear. If we learn about these traditions, we’ll be able to talk to our neighbors and say, this is something we have in common.”

The exhibition includes work from multiple artists who have made work for the Día de Muertos parade, which winds from a warehouse on Mill Street to Bregamos Community Theater in the city’s Fair Haven neighborhood. Since 2011, the parade has had an annual theme, including the anniversary of the Elm City Resident Card, homage to migrants who die aboard La Bestia (also called El tren de la muerte and El tren de los desconocidos), a freight train on top of which migrants ride as it cross-crosses Mexico, and most recently destruction of the rainforest and of the planet.

For those who have attended the festival before, it is a moving trip down memory lane. In a main gallery, there is a carefully assembled ofrenda, decorated to welcome the dead with a series of votive candles, old photographs, and painted skulls that shine in the overhead light. Surrounding installations reference Nero, a police dog who ended up biting a cop after he was sprung on pro-immigration protesters in 2017; they pay homage to migrants who have perished on La Bestia, with paper skeletons that wave from a series of train cars strung with twinkling lights.

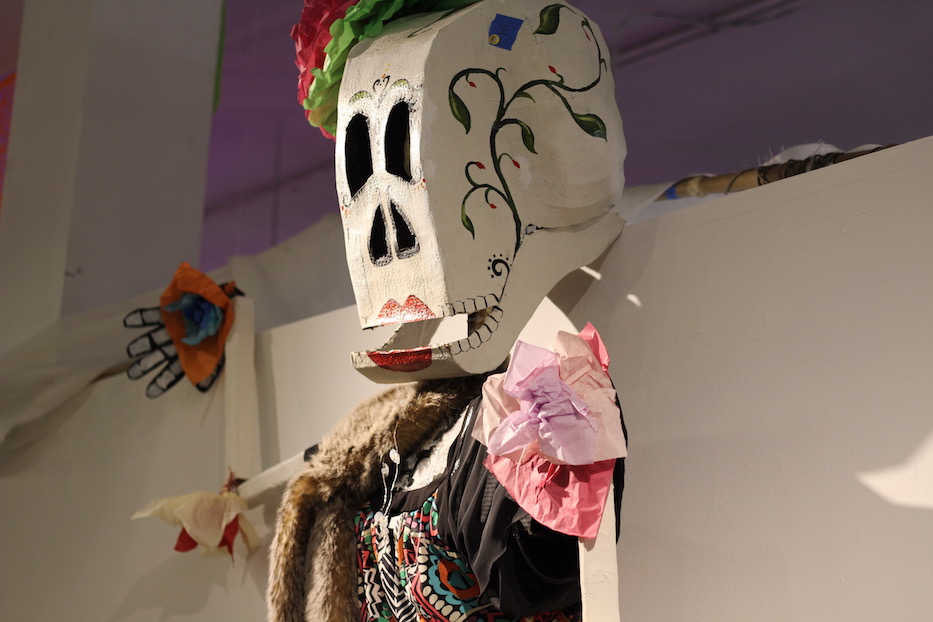

In each room, there are huge papier mâché sugar skulls and flower-studded skeletons that have multiplied over the festival's nine years. But there are also surprises that members of the public may have missed, including a 1996 wearable Sun Burst Mask, designed in the style of bright Puerto Rican vejigante masks by ULA Co-Founder John Lugo and the International Festival of Arts & Ideas when it was still in its fetal stages.

Some of the works stand out as particularly timely. In a gallery close to the far end of the building, a huge, sharp-beaked bird of prey descends on the ghost of Uncle Sam, who for López (and thousands of others, he suggested) represents the destruction of Latin America at the hands of cyclical U.S. governmental intervention. As the bird spreads its huge, fiery wings, Uncle Sam stares into the ceiling above, smaller skeletons crawling over his blue-blazered corpse.

There are constant reminders of migration, and the fact that it is exacerbated by climate change at one end, and nationalist policies on the other. Viewers can walk right up to a sculpture honoring Samir Flores Soberanes, a Mexican activist and journalist killed on the doorstep of his home earlier this year. In a gallery facing out into the street, curators have included segments of a two-sided “border wall” that ULA created with Mexican artist Emilio Herrera Corichi for its 2017 parade, in which a skeletal George Washington looks out from a dollar bill, a bony foot beneath it and an American flag in the background.

First created in the wake of Donald Trump’s presidency, it echoes loudly now, as hundreds of thousands of Latin American migrants are held at the border, denied asylum, and turned back into Mexican border towns under the Trump administration’s Remain In Mexico policy.

“We have always migrated—that is the history of the world,” López said. “But for the past several years, borders have become difficult to explain … this barrier [the wall] represents injustice.”

On another gallery wall nearby, viewers have a chance to get to know—and to mourn—Latina women who have lost their lives because of their sex. In 2018, organizers dedicated the parade to four victims of partner, domestic, sex worker, and state violence: 20-year-old Claudia Patricia Gómez Gonzáles, who was shot dead by the U.S. Border Patrol, 33-year-old Roxana Hernandez, a transgender woman from Honduras who died in Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody in May, and former SWAN members Leila Riviera and Ines Perez.

At the core of the show, and what makes it feel so very unique, are López’ kites, some huge and vivid and others simple, with a chilling depth that requires close looking. On the long wall that runs parallel to Artspace’s front entrance, he has installed a 40-foot work made entirely of paper, string and bamboo, marrying traditions from Guatemala with symbols of ULA.

“The kite is the connection between the supreme god and the dead one, and the family who are on earth and the spirit that is high in the sky,” he has written in an accompanying booklet, translated from Spanish by Artspace’s artist-in-residence Anatar Marmol-Gagné.

In a third, López has installed a very different display of kites, a constellation of 43 white flags honoring the 43 students who disappeared from Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers’ College in September 2014. As they unfurl on web-like strings straight from a skeleton's palm, 43 faces and names seem to look straight back at the viewers, a plea to honor them with the act of not forgetting.

For López, that’s part of the point: humans are intimately tied to death because it’s the last thing they do, and the one thing they all have in common. At times, the line between the living and the dead is whisper thin, particularly for families that have members on both sides. The exhibition, like the celebration it lifts up, is a chance to bridge those worlds.

“The dead are always with us,” he said.

Artspace New Haven is located at 50 Orange Street, New Haven. Hours and more information are available here.