Culture & Community | Faith & Spirituality | The Hill | Tower One/Tower East | Youth Arts Journalism Initiative

| Caleb Crumlish Photo. |

Tagan Engel grew up hearing about the Holocaust from grandparents who barely escaped it and dedicated their lives to telling the tale. As she learns to live in a world without them, she is keeping their story—and thousands of others— alive.

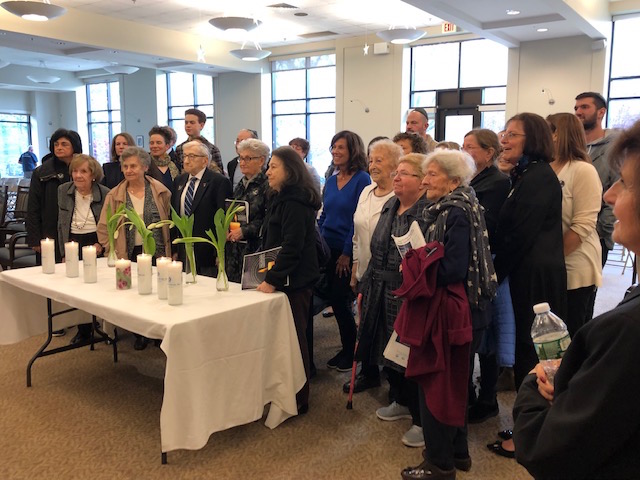

Engel gave the keynote at an annual Yom HaShoah Commemoration, held Sunday to remember the six million Jews who were tortured, worked to death, and systematically murdered during the Holocaust. Organized by the Jewish Federation of Greater New Haven and several local synagogues, the commemoration took place at Tower One/Tower East assisted living facility in the city’s Hill neighborhood.

Before the keynote, New Haven Mayor Toni Harp gave brief remarks, declaring the day “A Day of Remembrance of Victims of the Nazi Holocaust.” Ruth Lesser, chair of the Holocaust Memory Committee, invited resident survivors and their families to each light one of six candles representing the six million Jews who perished in the Holocaust.

Youth representatives from the B'nai B'rith Youth Organization (BBYO)’s Connecticut Valley Region lit the seventh to signify “Light in the Darkness.” State Sen. George Logan also came onstage to place a white flower in memoriam and read a poem.

The main draw of the event was Engel, the granddaughter of Holocaust survivors Chaim and Selma Engel. Born and raised in New Haven, Engel grew up hearing about her grandparents’ escape from Sobibor, a Nazi death camp constructed during the German occupation of Poland in 1942. Since their death—her grandfather 16 years ago and her grandmother last December —she sees it as her responsibility to keep their story going as a third-generation survivor.

“I have realized that it is now my turn to stand up and speak,” she said, calling on attendees to recite the Shehecheyanu together as a way to bless her first in presenting the address. “It is not an easy thing to carry on this responsibility, to share their powerful story, to share its impact on me and how I understand our next generation’s work of Tikkun Olam, the Jewish notion of repairing the world.“

Engel took the audience back to Europe of the 1943, as her Dutch grandmother Selma (then Saartje Wynberg) was captured and deported to Sobibor in what is now Eastern Poland. There, Ukrainian guards forced her and other Jews to dance together for the sole purpose of their entertainment. Wynberg met Engel’s grandfather, Chaim, when the two were placed together.

“It was while being forced to dance together that the two of them began to fall in love, even in the midst of this most horrific and unlikely of places,” Engel recalled.

The heartbreak and horror was a daily assault. In the camp, Chaim was forced to sort the garments of fellow Jews who had been gassed to death. It was how he discovered his father and brother had been murdered. It was also how he and Selma found themselves among hundreds planning a revolt and escape, because death was likely the other option. And how he summoned the courage to kill a Nazi guard, proclaiming that it was “for my father, and my brother, and for all the Jewish people!” according to Engel.

Her story kept the audience suspended in silence. From her grandparents’ escape, she chronicled their reliance on each other and on the kindness of strangers, the nine months they spent hiding in a loft falling in love, and their journey from Poland to Holland, then to Israel and ultimately to the United States. She recalled a childhood that was hard and sometimes traumatic for her mother and uncle, and drew parallels between her grandparents’ immigrant experience and the treatment of people of color and undocumented immigrants in the U.S. today.

“In Selma’s hometown [in Holland], they found themselves again treated as less than citizens and sometimes as less than human,” she recalled. “An experience sadly that so many undocumented people in our country experience today.”

When they were still alive, Chaim and Selma told that story, speaking to both schools and to family about the horrors they had witnessed (it sprang into wider consciousness with Richard Rashke's 1982 Escape From Sobibor and a movie of the same name five years later). Now the host and writer for The Table Underground, Engel has kept the history alive, including on her own trip to Poland last October to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the escape and a new museum that is going up on the site of the camp (read and listen to her reflection here).

In her keynote, she also recalled several earlier trips to Poland, Holland and Israel to “meet the family I had only known by name” and experience her grandparents’ journey for herself. She drew the audience into the present, offering the commemoration ceremony as both a time to remember and a time to act.

“When I remember specifics things about the Holocaust, the ghettos, the transports, the concentration camps, and dehumanization ... it also makes me remember genocides and massive suffering of other peoples,” she said. “Genocide in Rwanda, and Sudan, and of Native Americans here, the oppression of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank, and Asylum seekers fleeing for their lives at our southern border being treated like criminals and caged like animals.”

She added that she sees echoes of the Holocaust in shootings at schools and houses of worship, and in police brutality and officer-related violence in the streets of the country and of New Haven. She urged attendees to learn from the atrocities of the Holocaust and find their own way to repair the world.

After Engel spoke (read her full remarks here), several prayers, poems and psalms were read in Hebrew. Holocaust survivor Isidor "Izzy" Juda read off a list of all the camps where Jews were kept, forced to work, and systematically murdered. The event closed as attendees sang Hatikvah, the national anthem of Israel. The anthem comes from the first stanza and refrain of the original nine-stanza poem Tikvateynu, written by the Jewish poet Napthali Herz Imber.

After the event, Juda said that he believes it’s “important to remember this event.” To help preserve knowledge of the Holocaust, he frequently visits middle and high schools to discuss his experiences.

“The kids are respectful, and ask intelligent questions,” he said. He recalled a visit during which a student asked him, “How do you feel about Judaism now that you’ve lived through the Holocaust?”

“I still believe in God," Juda replied. "I believe it was thanks to God that I survived.”

This piece comes to the Arts Paper through the second annual Youth Arts Journalism Initiative (YAJI), a program of the Arts Council of Greater New Haven and the New Haven Free Public Library. Over eight weeks this spring, ten New Haven Public Schools (NHPS) students will be working with Arts Paper Editor Lucy Gellman and YAJI Program Assistant Melanie Espinal to produce four articles, for each of which they are compensated. Read more about the program here.