Co-Op High School | Creative Writing | Education & Youth | Poetry | Arts, Culture & Community

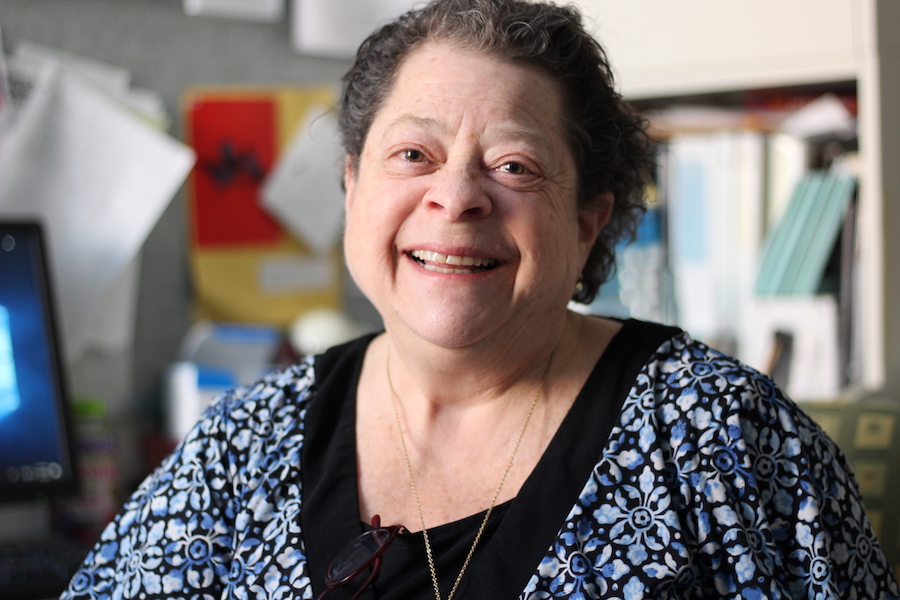

| Judith Katz. “Creative writing is one of the best kept artistic secrets going, especially in this town," she said at one point. "And I guess at this point in our development, we need to be less of a secret.” Lucy Gellman Photo. |

Dozens of students, faculty and alumni at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School (Co-Op) are speaking out in defense of creative writing as the New Haven Public Schools district completes a full curricular audit, and the Board of Education prepares to present its proposed budget to the Board of Alders.

As of Thursday, NHPS Chief Operating Officer Michael Pinto said that he was not aware of any proposed reduction in the program. But over the past month, teachers and current and former students have sent written testimony to Superintendent Carol Birks in favor of the program.

Currently, Co-Op’s creative writing program offers one freshman class, one sophomore class, and two classes for juniors and seniors (view more on the courses here). Each year, the program is also responsible for the publication of Metamorphosis, a journal of student poetry and prose illustrated with student art, and for Co-Op Voices, the school’s online student newspaper.

In addition, several students are featured each year in Connecticut Student Writers, a statewide collection of student writing published each year by the University of Connecticut. Of a total student body of almost 650, close to 100 have declared creative writing as their art.

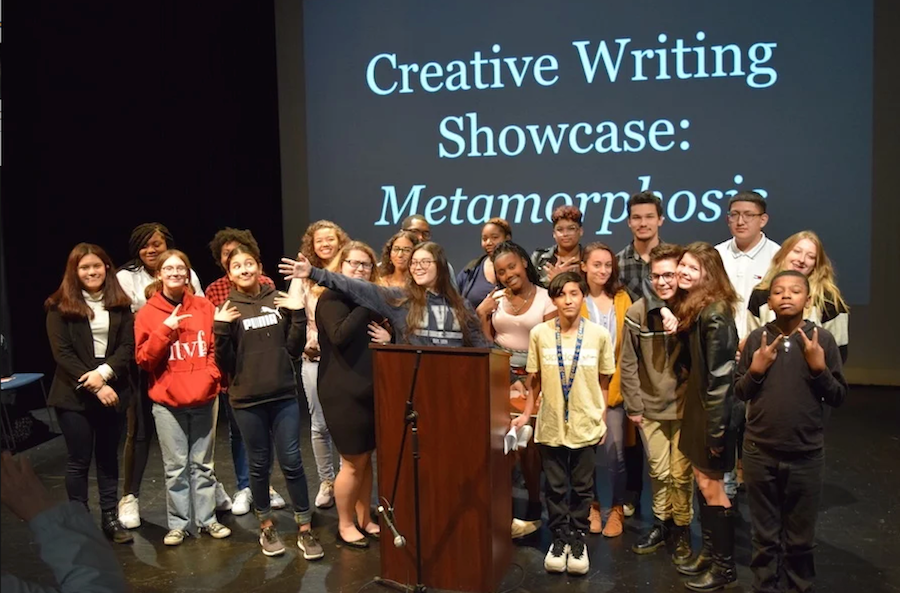

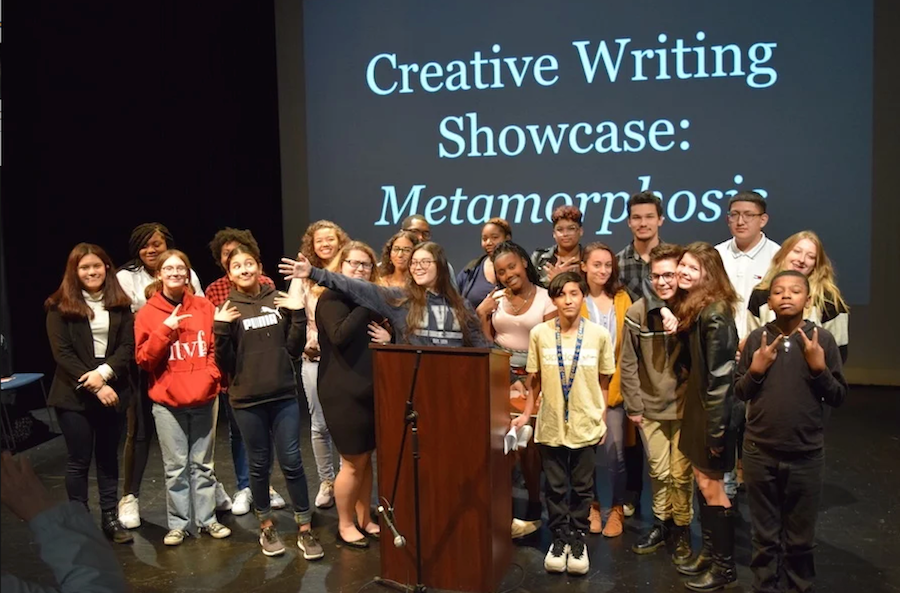

| Students at a showcase reading for Metamorphosis 2018 in October of last year. Robert Esposito Photo. |

“I think creative writing is at the core of virtually all the arts,” said Judith Katz, one of three instructors in the school’s creative writing program. “If you don’t have writing, you don’t have theater. If you don’t have writing, you don’t have song. Everything kind of comes down to the word at some point. It actually gives people a voice.”

For Katz, the problem is bigger than the NHPS budget alone. Outside of Co-Op, creative writing is not included in the National Core Arts Standards or the Connecticut Arts and Standards, which are based on the national model and include dance, music, theater and visual arts. In part, that’s because reading and writing are included in English Language Arts Standards, set by the Common Core State Standards (CCSS).

“The area of creative writing (and poetry) is typically included in English language arts,” said Marcia McCaffrey, an arts education consultant with the New Hampshire Department of Education and a spokesperson for the National Core Arts Standards, when reached by email.

She pointed to the CCSS for writing, the high school versions of which ask students to hone their analytical writing skills, produce two-sided arguments, work on essay structure and flow, and integrate research into essays.

But Co-Op’s writing teachers have seen the consequences of that format on the school. Unlike teachers in music, dance and drama, creative writing instructors are certified to teach high school English, meaning that they can technically take on those classes if the school asks them to.

When an English teacher left two years ago, creative writing teacher Aaron Brenner absorbed his classes. That translated to fewer creative writing courses for the department. Two years later, the program has continued to shrink, to balance a higher load of English classes that teachers in the department have had to take on.

| Mindi Englart: “People don’t know we’re here. We’re a small, quiet art and there’s nothing like us. There’s nothing like us in the state, there are very few things like us in the country at the high school level. Instead of us going away, there should be more programs like ours.” Lucy Gellman Photo. |

But that solution doesn’t work for Co-Op’s creative writing teachers. Mindi Englart, who joined the school 16 years ago, suggested that English can’t absorb creative writing—one discipline is dedicated to creating original art while the other is dedicated to studying and critiquing it. She pointed to Bloom’s Taxonomy, noting that the very tip of the triangle—producing original work—dovetails with what she teaches each day in her classroom.

“We fit with arts standards, not English standards, because we create the work that people analyze,” she said. “In English, they analyze and learn from works of writing. But we actually make the work. We’re artists. We make the work that other people are affected by. That’s what creative writing is. It’s an art. We may do some similar things, like analyze, but it’s in order to create.”

“I think in creative writing, you’re sort of obligated to the responsibility of speaking to everyone through yourself,” added Katz. “And I think that is at the heart of creating art—that you are knowing yourself and working with yourself in a way that when you present it, it’s relatable.”

Now, there is a swelling chorus of voices behind her. Reached by phone earlier this month, Co-Op's inaugural arts director Keith Cunningham called the program an indispensable part of arts learning, honing in on the way Metamorphosis and Co-Op Voices help students learn both the creating and editing processes.

“The support kids give each other as they find their voice is phenomenal,” he said.

Cunningham joined the school in 1990, when it was still in its very nascent stages at 800 Dixwell Ave. At the outset, he said, the creative writing curriculum was fairly loose—decisions were left to teachers, almost all of whom were part-time. Funding left the school hanging in limbo: it was steady, then it wasn’t, then it was again. In the early 2000s, Cunningham described the school as finally “on steady footing,” so much so that faculty began to come on full time, and stay for more than a year or two.

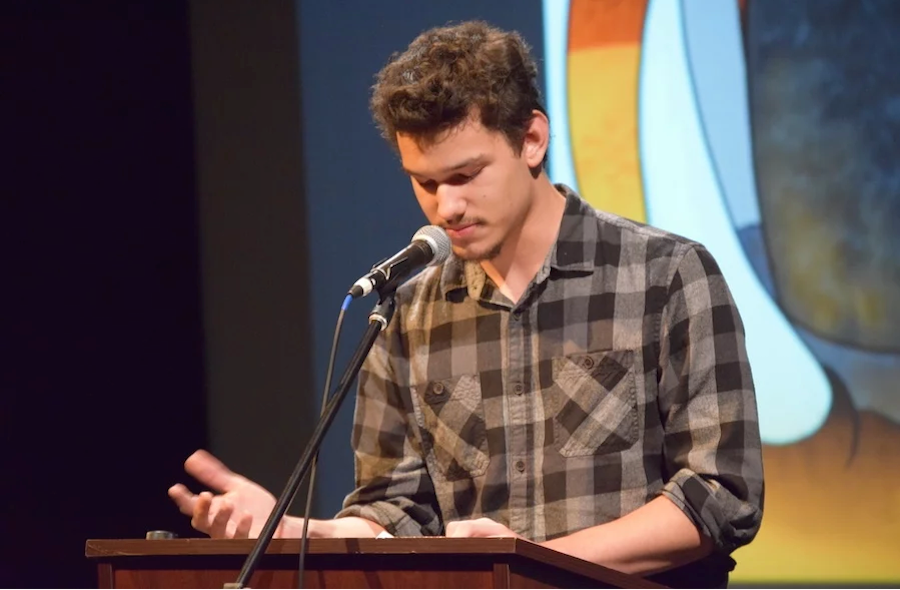

| Pablo Sanchez-Levallois reads at a showcase reading for Metamorphosis 2018 in October of last year. Robert Esposito Photo. |

In those years, teachers began to streamline the curriculum (more recently, Brenner also wrote a series of academic benchmarks for creative writing in keeping with the Connecticut Arts Curriculum Framework). The department came into its own, adding offerings in fiction, poetry, playwriting and screenwriting. If the program were to be absorbed by the English department, Cunningham said, “all that independent creative work is likely to be lost.”

“The English department has a very specific curriculum, much of which is outlined from the state,” he said. “Creative writing, from the outset, has been looking at production and publication and developing a creative voice. The focus is more on getting the kids to write, and to write and to write and to write, and then to edit and polish.”

Journalist, author and East Rock Record supervisor Laura Pappano echoed those words in a phone call earlier this month. As a fellow writing mentor—she visits Englart’s class about once a year—she said she is constantly impressed by how New Haven students “really have a lot of confidence about their ability to create and to be creative.”

“Writing is not just about grammar and language—it is really about thinking,” she said, recalling a recent trip to Englart’s class where she and students pored over news photographs. “Teaching creative writing really helps people understand the way they think, in a way that they don't get if they’re not doing that.”

“Getting a grasp of how to express yourself clearly and succinctly is really valuable, and it serves you even if you're not going to become a poet or journalist,” she added.

| MarQuel Woods in an interview last year. Lucy Gellman File Photo. |

That’s also true of many of the department’s current students. Four years ago, MarQuel Woods began his studies at Co-Op with dreams of becoming a novelist. He was a quiet freshman: teachers noticed that he didn’t say much, but spoke with purpose and care when he did. He excelled in his creative writing classes, turning to his poetry and prose not just in the classroom but at home, where his relationship with his mom often became strained.

Then his junior year, she was struck and killed by a motorist on Ella T. Grasso Boulevard. While the two hadn’t always gotten along—“she had her issues and I had mine,” he said in an interview last year—they loved each other deeply. Her death was a sudden, striking blow. He said that writing a poem entitled “Free” (read excerpts of the poem here) helped him cope.

“It felt cathartic to get all those complex feelings about her death out into words,” he said in a phone call earlier this month. “Creative writing and art in general is a great way to work through emotions and thoughts.”

“I would say that creative writing is just like any other art,” he continued. “We create to inspire, to entertain, to educate. It is the foundation of almost any other art—you need written word to create everything else.”

In the fall, he will start at Bard College, where he plans to study writing. He said that he hopes to continue on to a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing and ultimately become a professor.

| Nadia "Navi" Gaskins: "Writing is basically like breathing to me, like air." Lucy Gellman File Photo. |

Sophomore Nadia “Navi” Gaskins had a similar experience her freshman year. During the previous three years at King-Robinson Inter-District Magnet School, she said she was bullied for her sexual identity, then cast out of her friend group when she came out as bisexual. In the school hallways, she heard a litany of names: slut, lesbian, whore, worthless, useless, waste of space, disgrace. She recalled being so depressed when she graduated that she considered self-harm.

When she got to Co-Op, she made the decision to write her experience down. She filled pages and pages, editing it into poem form while also joining writing initiatives in the Co-Op After School program. After publishing in Metamorphosis 2018, she presented her poem “Take. Them. Back.” at a reading last year.

“Writing, in general, saved my life,”she said. “It was my outlet. Whenever I'm having a panic attack, I repeat my poems. Writing is basically like breathing to me, like air. It's my way of leaving my mark here. My writing is me. It's a part of me.”

This year, she’s used her poetry as an educational megaphone, advocating through verse for more thorough teaching of Black history (which, she pointed out, is simply American history) in New Haven schools and across the state more broadly. After watching a spoken word piece that Englart played for her class, Gaskins said she realized how little Black history was being taught in school. Her poem, “The Hammer Of History,” responds to it. An excerpt reads:

Black. History

I’ll say it again.

BLACK. History.

Dragged through the sludge of concealment.

Sewn together with the needle of ignorance, And the threads of oblivion.

Locked away six feet/Under

In the casket of abandonment. This can’t be known, never tell.

| Samantha Sims during the first year of the Youth Arts Journalism Intensive in spring 2018. Lucy Gellman File Photo. |

There are students like Sims, who used poetry and prose to get through the death of several family members last year. In spring 2018, she received news that her grandmother had died, and her grandfather was sick. Her aunt had died of cancer just months before. When she flew to Jamaica to bury her grandmother, she spent time with her grandfather, noticing how weak and frail he’d become.

“It's just like—you know when you're going to see somebody for the last time?" she recalled. “I was going from not being able to say goodbye to my grandmother to knowing I was going to see my grandfather for the last time.”

In Jamaica, she watched her older brother break down in grief. Nine years her senior, he had been raised by her grandfather, and looked to him as a dad. Sims struggled seeing his grief while trying to also deal with hers. When she returned, she began working on a piece titled “Last Night.”

"That was my final goodbye,” she said. “It was coming to terms with everything around his death. I can definitely say that piece really helped me channel it."

Now, Sims also writes for Co-Op Voices and has done freelance work for the Arts Paper, covering art within her school and the community. She said she plans to work on a capstone on the ways creative writing helps students deal with trauma.

| Creative writing alum Melanie Espinal, who went on to SCSU and now teaches NHPS student journalists and writes professionally. Lucy Gellman Photos. |

Several alumni have also parlayed their creative writing experience into journalism. After graduating from the department in 2014, Melanie Espinal studied journalism at Southern Connecticut State University (SCSU), serving as a writer and editor for Southern News and the founder of Crescent Magazine.

When she graduated from college last year, she went on to work for the Westport News, Cottages & Gardens Magazine and the Arts Council of Greater New Haven, where she is a program assistant for the Youth Arts Journalism Initiative and freelance reporter for the Arts Paper.

None of that would have been possible, Espinal said, without the department. In early April, she submitted testimony to the Board of Education, asking Schools Superintendent Carol Birks not to make further cuts to the program. In the letter, she recalled the first time she saw her work in print, proudly bringing a copy of Metamorphosis home for her family and feeling its weight in her hands. She praised the department for helping her cultivate her voice, which she has since used for news writing.

“Would I, a 14-year-old girl living in poverty from Fair Haven, be given one-on-one feedback with experienced writers ... if the program had got its funding cut long before I was accepted?” she asked in the letter. “Would I have been given the opportunity to see what a writing community looked like? Would I have been exposed to non-fiction as not just this boring section of books in the library I always avoided but instead the heart-wrenching, sad, funny, analytical and unifying storytelling that it can be? Probably not.”

“I am very grateful to the creative writing program at Co-Op and would be torn if the program were to be even smaller than it already is,” she added. “We need writers. We need writers to contextualize the world around us. We need writers who look like us, grew up like us and are trained in fiction writing, nonfiction writing and poetry. We need them to tell their stories. We need them to tell the stories of those who cannot do so for themselves.”

Jessica DiLieto, who graduated two years before Espinal, also wrote into the Board of Education, praising the department for its guidance and support. As a kid, DiLieto lived in foster care, ultimately adopted by her grandmother. She turned to writing as an outlet, world building in journals that seemed to multiply by the month “with the millions of characters I had created.” When she was accepted to Co-Op after middle school, she felt like a dream was coming true.

But at Co-Op, she struggled to balance academics and her personal life. At home, her grandmother was sick. Her uncle struggled with his health. In the creative writing department, teachers urged her to write it down, and gave her examples of poetry and prose where writers were doing that work. It saved her from failing out of high school.

“At the time, I always felt like a failure of a student because of my bad grades in school,” she wrote to Birks. “And I looked forward to writing class every day because it was something I was passionate about. When everything in my life was falling apart and I couldn’t do anything about it I at least had my storytelling to protect me.”

When DiLieto graduated—she wore her creative writing sash proudly, she recalled—she continued writing in classes at Gateway community college, and went on to do work in journalism.

“Creative Writing is a quiet art,” she wrote. “But it doesn’t take away from how mighty we can truly be.”