Culture & Community | LGBTQ | Music | Arts & Culture | New Haven Pride Center

Maia Leonardo at a "Trans and Talented" open mic night in November 2018. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

Maia Leonardo always had something to say. At rallies across the city and the state, it was the promise that another world was possible. At her lunch breaks, it was unrestrained praise for cold cheese pizza and sliced pastrami sandwiches. At the keyboard and in prayer, it often involved no words at all. And always, she made the space to listen for a response.

Now, friends and family are struggling to adapt to a world without the certainty of her voice. Leonardo, a beloved New Haven musician, trans rights activist, community organizer, doting cat mom, daughter, older sister, and member of the Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL) passed away at home on Aug. 30. She was 28.

“I keep thinking back to the first conversation that Maia and I had, where she came out to me, and she told me her name,” said her friend Kirill Staklo, a fellow trans rights activist and member of PSL. “Since then, she’s become this huge lighthouse, this huge beacon of light to not just the trans community, but to people in so many different spheres of work.”

Leonardo was born in Philadelphia, the eldest daughter of Kathleen and Jim Leonardo. Raised between Philly and North Carolina, “she was precocious,” Kathleen said in a phone call last week. “A really happy go lucky small child.” She was also fiercely creative, from drawings of furry woodland creatures with backpacks and headphones to piano lessons that laid the very early groundwork for Juno Hawke, the moniker under which she produced and performed in New Haven.

Even then, her generosity became one of her most defining characteristics. When she was five or six, Leonardo was out to dinner with her family when she made her first charitable donation. As her mother remembers it, her child-sized pockets were filled with quarters so she could play nearby arcade games. Then she saw a donation card—“I think it was a kid with muscular dystrophy,” she recalled— and instinctively dumped every quarter she had on the card.

“In families, we hope to be inspirations and role models for our children,” Jim Leonardo said at a memorial on Zoom earlier this month. “But in our family, that went both ways.”

Leonardo during a virtual performance for Lesbian Visibility Day in April of this year. “However you choose to define yourself is totally valid and worthy of celebration,” she said before her performance. “There’s no such thing as queer enough, or bi enough, or lesbian enough. However you express your queerness is totally valid.”

Years later on family trips to New York, she didn’t hesitate to part with whatever money she had. She “would give away her train fare” if someone asked, Kathleen said. Then she would figure out another way to get home. Years later she did the same for friends and community members, including most recently as a volunteer with the Semilla Collective, the city's Medical Reserve Corps, and a drive-through Covid-19 testing site on New Haven's Long Wharf.

As Leonardo got older, she studied the world around her with a clear-eyed, sharp focus on everything that grabbed her attention. At 10, she became the youngest student ever in North Carolina’s network of community colleges, where she flew through computer science courses. In high school, she brought that same enthusiasm to choir practices and at-home gaming after a family move to Cooperstown, New York. She was drawn endlessly to the history of her grandparents’ native Ireland, immersing herself in the country’s timeline of colonialism, struggle, and revolution.

The fact that she led with empathy shattered stereotypes, Kathleen Leonardo said. Early in her life, Leonardo received a diagnosis on the Autism spectrum that she was later very public about, including in a panel on queerness and Autism at the New Haven Pride Center last April. Counter to a lingering stigma, Kathleen said, it never meant that her daughter was aloof or detached. Instead, her starting place was a deep desire to help.

“She felt things just so strongly,” she said. “If she thought about what somebody was going through or what suffering they might be having, she felt as though it was her.”

In Cooperstown—population 2,000—people looked out for her, and she for them. During a memorial service on Zoom earlier this month, her former next door neighbor recalled a night that Leonardo, acting on intuition alone, sprinted across the driveway, hauled him into her car, and drove to the hospital. Because his wife was out of town, she stayed with him, sleeping on the hospital floor, until someone else could get there. He said that her quick thinking saved his life.

“She had a sense of humor and compassion unlike anyone I’ve ever met before,” said Cynthia Robinette, a friend of hers from high school. “We love her. We’ll miss her. Certainly, her hugs were something to treasure. They were big and warm.”

Leonardo moved to New Haven almost 10 years ago, growing her activist footprint as she worked part-time jobs in development and customer service at Neighborhood Music School, Central Connecticut State University and later the New Haven Pride Center. It was in the Elm City that she became a fixture at rallies, protests, open mic nights and performances, PSL movie screenings, and fiery-but-funny speeches against imperialism (“genocidal goblin Henry Kissinger” was one of her most memorable lines, Staklo said). She was known for her candor and her warmth, giving out what PSL member Chris Garaffa later dubbed “those Maia hugs” at her memorial.

Seven years ago, Staklo met her through Justice for Jane Doe!, a movement to release a 16-year-old transgender teen referred to as “Jane Doe” from York Correctional Facility. At the time, Leonardo was in the process of coming out, and looked to Staklo as a mentor. Staklo, in turn, remembered feeling floored by how much of the “all the unsexy and deeply necessary background work” Leonardo was willing to do as she also found and raised her own voice for trans rights.

“Whether people admit it or not, people expect us to hold and carry and process a lot more pain than the average person,” he said in an interview at the Coffee Pedaler last week. “I think people associate trans-ness with pain, and by virtue of that they bring pain into our lives. And Maia was very much the opposite of that. Everything she did in the community was light. It wasn’t pain. She, like, photosynthesized all of her own struggles into breaths of fresh air for everyone all the time.”

The two became fast friends, sometimes talking for hours after an event had ended. Often, Staklo was amazed by Leonardo’s energy and capacity for care in the midst of organizing. A member of both PSL and Trans Lifeline, where she later sat on the board, Leonardo still checked in with her friends, blossomed professionally, and churned out a full album as Juno Hawke. In late August of this year, she prepared to report to Hill Regional Career High School as a member of the Medical Reserve Corps, on standby in case New Haven got walloped by Hurricane Henry.

Staklo and Leonardo during a Trans Day of Remembrance rally on the New Haven Green in November 2019. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

Staklo and Leonardo during a Trans Day of Remembrance rally on the New Haven Green in November 2019. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

It seemed that every hat she wore, she wore it well. She took famously good care of her cat, Leon. She became an informal spokesperson for bolo ties. She would pray for friends who were struggling or in pain, often asking for their consent before she did. If she came over for a board game night, she “would completely wipe the floor” with her opponents, Staklo said—usually after delivering a warm, all-encompassing hug.

Karleigh Webb, a fellow trans rights activist and member of PSL, remembered her as containing multitudes. The two often spoke at the same rallies and events, urging fellow activists to keep fighting.

“She was a check that provided a lot of balance,” Webb said during her memorial. “She was red like me, trans like me, and she was someone I aspired to be. You could see the joy when she performed her music … and you could see that in her comradeship. Comrade was a word that fit her perfectly. We’ll miss you, but we know that we will continue the work. Because you’d check us if we didn’t.”

Leonardo also led with that spirit when she began working at the New Haven Pride Center, where she was the marketing and development coordinator from November 2019 until June of this year. When she began writing the center’s weekly newsletters, Executive Director Patrick Dunn fell in love with her sense of careful, sometimes gravity-defying optimism. Even when the world seemed very dark, he said, her voice prevailed.

It flowed from her speeches at Trans Day of Remembrance rallies right back to her desk at the center’s Orange Street home. It became a steady presence as the center faced escalating attacks on trans rights during the last years of the Trump administration. When Covid-19 hit the city last March, she got the center’s programming online in just days, then worked with Dunn to help get food to hungry community members through its weekly food distribution program.

In a newsletter the first week of the pandemic, she coined a sentence—that “transphobia, homophobia and biphobia thrive in isolation”—that became the center’s mantra. It still is, Dunn said.

“For me the best way to remember anyone is to honor them and live the way they would have wanted you to live,” he said. “In the case of Maia, she was a fierce advocate in the community. She was a fierce advocate for the underrepresented, and the way that I can honor her is to continue the activism and the work that we did together, and sometimes separately, and have her energy as wind under my wings.”

Center Administrative Coordinator Laura Boccadoro, who shared an office with Leonardo until June, said that they find themselves missing small, everyday things about Leonardo’s presence, from the reliable squeak of her sneakers to a blanket that she kept draped over her chair. Last Christmas, Leonardo made mixtapes for everyone at the center. Boccadoro still keeps theirs close by.

After helping to clean out Leonardo’s house after her death, they kept a single sweatshirt, covered in pictures of cats. They and Dunn are in the process of donating her musical equipment to a school. Leonardo's clothes went to the Center's clothing closet.

“The positivity she radiated sometimes, it froze you in your tracks almost,” they said in a phone call last week. “I’m still having a hard time talking in the past tense about her.”

Juancarlos Soto, director of case management and support services at the Center, said he is still processing. While working together, he and Leonardo discussed everything from legislative policy to the rules of Dungeons & Dragons to the best pastrami sandwich in New Haven. The last, it turned out, existed right down the street from the Center at Ninth Square Market—and always came with extra pastrami.

“I don’t think people always saw that side of her,” he said. “I think people saw this very quiet person. I got to see this very passionate person she was, whether you were on the side of her that she agreed with, or the side of her that she didn’t agree with.”

Leonardo also built a robust online and long distance community, connecting with fellow LGBTQ+ activists, trans support and affinity groups, and members of PSL who were out of state, many of whom praised her support, guidance and patient, open ears at her memorial. Last year, she began talking to fellow activist Callie Mill, a member of the PSL who became her partner.

At Leonardo’s memorial earlier this month, Mill spoke about the strength that Leonardo gave them to transition, and the conversations that the two would have “morning, noon, and night.” In August, the two were able to spend time together before the fall started, and Leonardo poured herself into a new job.

“That’s what I remember,” they said. “All of the love she had for everyone.”

Honoring A Legacy Of Service

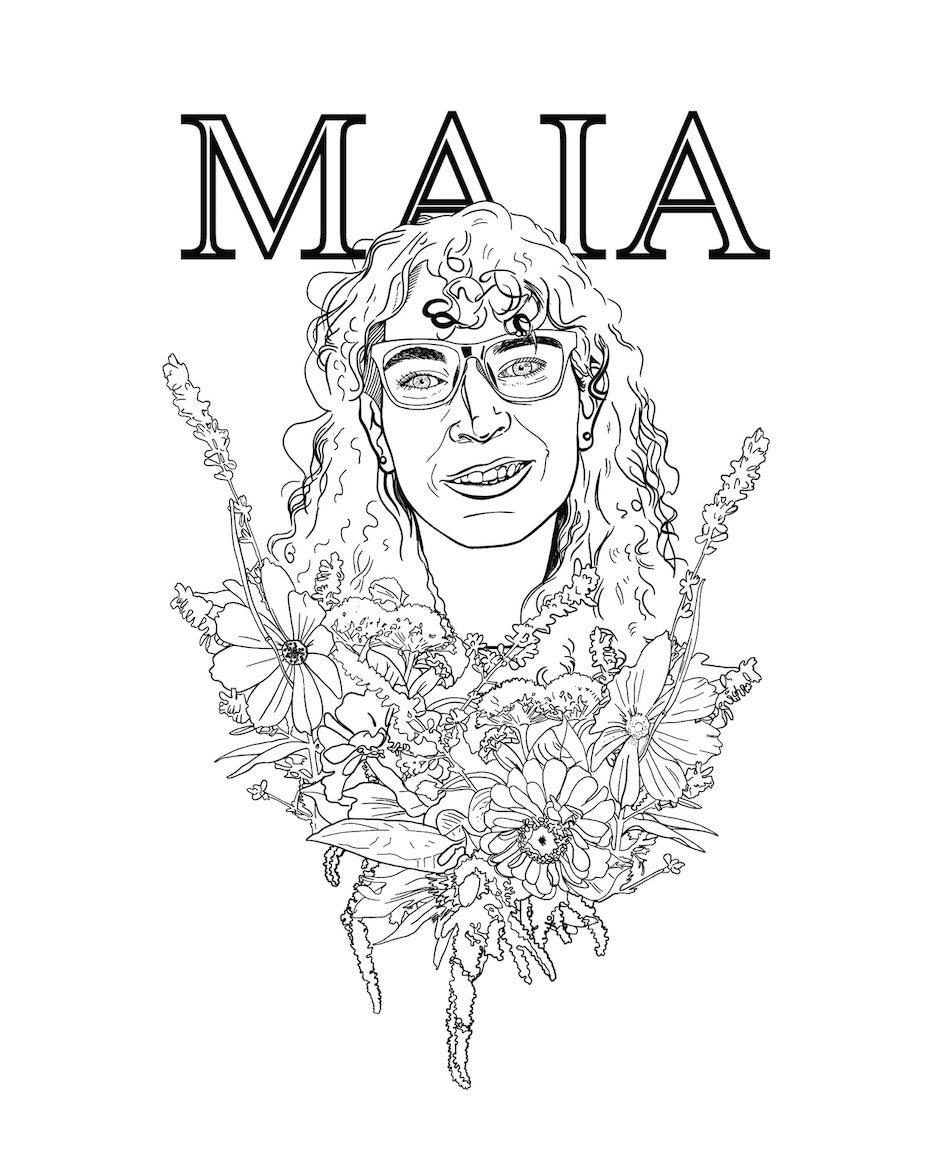

Sam Mashaw's illustration. Image courtesy of Sam Mashaw.

In the days since Leonardo’s death, friends, former colleagues, and family members have shared an outpouring of grief—and a commitment to continuing Leonardo’s work—online and in person. In a eulogy that she delivered earlier this month, Leonardo’s younger sister Anne said that she is working to think about “Maia’s present tense,” or that which remains after her sister’s physical body is gone.

When she read it at Leonardo’s memorial earlier this month, she urged listeners to hold onto her sister’s big-hearted generosity, to check in with friends and family, to seek out and “celebrate small joys,” as Leonardo so often did. She remembered her older sister’s flair for terrible jokes, electrifying blue hair dye, funny accents and activism wherever she thought the world needed it.

“I want Maia’s present tense to be that which will inspire us to fight for a radical reimagining of our world,” she read. “She saw injustice and oppression everywhere, and never hesitated to march in protest, or use her voice to call for a new way, or educate people on issues and how to get involved. She believed, passionately and militantly, that we could live in a world without poverty, where people are housed and healthy, where people are accepted and celebrated. May we keep Maia present by continuing the fight she devoted her life to and creating the future she imagined.”

Sam Mashaw, an artist in New Haven who is training to become a therapist, illustrated a black-and-white, coloring book-like portrait of Leonardo surrounded by flowers, smiling and full of light. The two met at a PSL movie night for Winnie, celebrating the life and work of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela. Immediately, Mashaw noticed how attentive Leonardo was to the new faces in the room.

While the two were acquaintances more than friends, Mashaw said, they traveled in many of the same social circles. The Friday night before Leonardo passed away, she performed with musician Evelyn Gray at Never Ending Books II, a State Street venue of which Mashaw is a founding member. Mashaw, who was not at the performance, said she is still grappling to make sense of the news that Leonardo is gone.

“She had a way of focusing her attention on you where you felt seen and welcomed as your whole self,” she said. “I have gratitude—for what she gave to the community, for what she meant to people. I think her memory and people’s desire to honor her spirit is going to continue to keep this community together.”

On social media, Leonardo's friend and fellow organizer Jules Larson mourned her passing as friends tried to make sense of it. Larson wrote that Leonardo had been many things to her—a fellow organizer, friend, confidant, and much-adored figure to her infant daughter Bella.

“I think back on her soft voice and realize only now that this is one of the voices I hope leads a revolution,” Larson wrote. “The voice of urgent patience, directness, bold intent, cherishing each and every soul she steps in front of.”

In an earlier obituary, Leonardo's family asked for donations to Trans Lifeline in lieu of flowers. Those can be made here. If you are trans and need to talk, the number for Trans Lifeline is 877.565.8860.