Co-Op High School | LGBTQ | Arts, Culture & Community

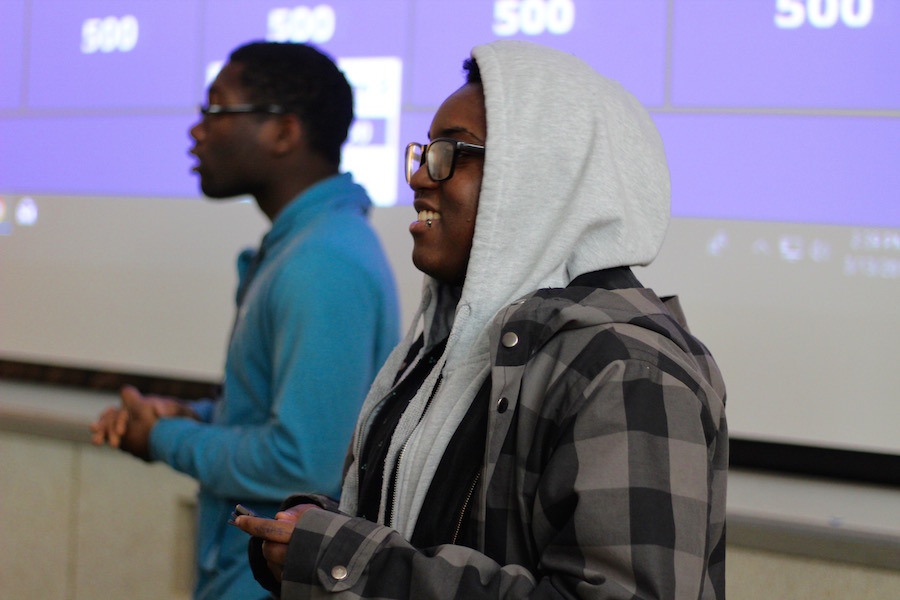

| Student Dayne Bell is one of the GSA members who worked on the design for LGBTQ+ Jeopardy. Lucy Gellman Photos. |

Dayne Bell was keeping an eye on sexuality for 400. He looked to the screen, back to the teams, back to the screen. Nervous competitors nibbled their lower lips. A question flashed in white and blue across the screen.

Bell read it off: what term describes a person who is attracted to other people regardless of their sex or gender identity?

Houston Cable’s hand banged down on Team One's bell before he even knew it was there.

“Pansexual!” he cried. “Pansexual!”

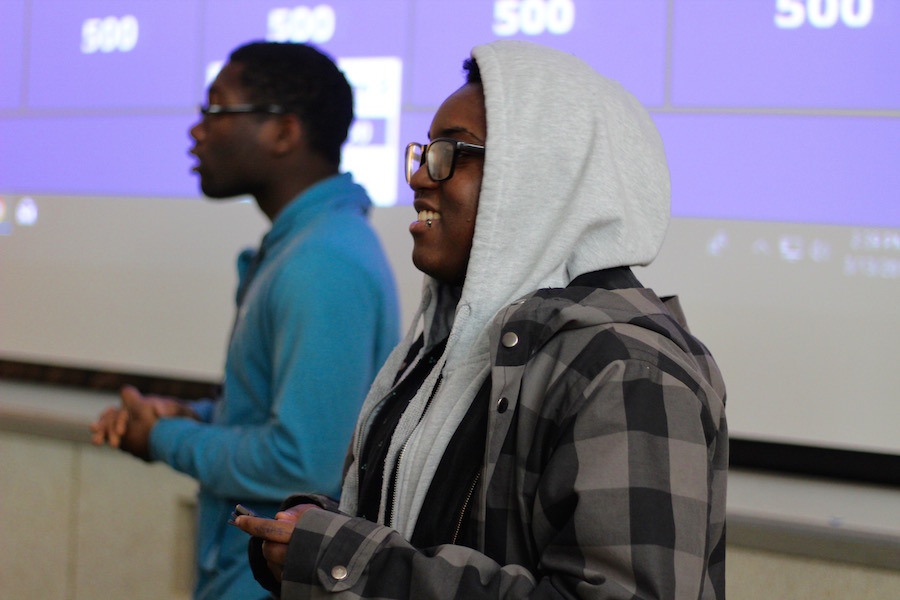

| Houston Cable, who helped design the peer-led "coming out" session for True Colors. |

Wednesday afternoon, that scene unraveled over and over again at Cooperative Arts and Humanities High School (Co-Op), as members of the school’s Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA) demoed a high-stakes game of LGBTQ+ Jeopardy for classmates, faculty, and residents of The Whitney Center in Hamden. Next week, those students will bring it to the 26th annual True Colors Conference in Storrs, Conn. as one of three workshops from the school.

“It’s immensely important for them to be in this group where they can be 100 percent them,” said Kelly Wuzzardo, a GSA mentor who serves as director of education and outreach for the Shubert Theatre, and has fostered a partnership between the two organizations for several years. “They can’t do that in all spaces …. I hear so many horror stories, and so it makes me so much more grateful that we have that outlet.”

Hosted by the eponymous Hartford-based organization, True Colors is the largest convening of LGBTQ+ youth in the country. Members of Co-Op’s GSA got involved with the conference four years ago, after linking up with the Shubert Theatre during its 2016 run of Kinky Boots. The Whitney Center, which is a Shubert sponsor, jumped onboard as part of its “Community Connections” program. This year, Co-Op is sending a larger group of students, part a push from the city and the New Haven Pride Center to sponsor 217 New Haven Public Schools (NHPS) students for that weekend.

| In attendance were Whitney Center residents Karen Kmetzo, Meryl Menon, and Bitsie Clark. "Make sure you are speaking loudly!" Clark reminded students after their demo presentations. |

Earlier this year, students started preparing for conference workshops in GSA meetings with Wuzzardo, Co-Op teacher Valerie Vollano, and West Havener Jillian Celentano, a student in psychology who started working with the GSA last year. Some have attended True Colors before; others are new to the conference (there are also freshmen, who are new to the school).

They devised three workshops: a game of LGBTQ+ Jeopardy, and versions of “coming out” story sessions for both students and adults. Wednesday, they kicked off the afternoon with the game show, pulling up a blue-and-white display that looked true to the long-running program on network television—except with categories dedicated entirely to queer history, culture, and terminology.

Filing into the first few rows of Co-Op’ lecture hall, attendees-turned-contestants scanned their choices: sexuality, gender, misconceptions, history of terms, and fun facts, all going from 100 to 500 points. A few murmured about real-like Jeopardy host Alex Trebek’s recent cancer diagnosis, and whether "playing" at home when the television was on gave them a competitive edge at school.

| Students Johan Elys, Danielle Botta and Houston Cable. |

As the first team deliberated over what category to hop on first, senior MarQuel Woods grinned, lit by the blue glow of a screen behind him. This will be his last conference as a student: Woods is headed to Bard College in the fall.

“Live dangerously,” he urged his fellow classmates, eyeing the screen.

Instead, they lived loudly and with echoing laughter, huddling in to discuss answers before shouting them out with each ding ding ding of the bells they’d been handed.

Giggles and groans followed questions in the “sexuality” category, as students reiterated the difference between sex and gender for their answers, then explained the definitions of “pansexual” and “asexual” for the room.

Students breezed through the definition of a drag queen, and why it means much more than a man lip-syncing in women’s dress. They explained what a "dead name" is succinctly, as if they have the answer ready to go at any time. When asked what event sparked a movement half a century ago, the room nearly exploded with gleeful proclamations of the word “Stonewall!”

| Victoria Mora, a freshman who is going this year. |

“What LGBT+ symbol started as one used by Nazis?” asked another question midway through.

“The pink triangle!” yelled someone from team two, ringing a cowbell high in the air. No sooner had it been spoken than the answer appeared on the screen.

But other questions stumped both teams. When asked the name of the psychiatrist who first came up with the term “transgender” in 1965, the room fell into near-complete silence. Wuzzardo, at almost a whisper, ventured a noncommittal guess of Alfred Kinsey from where she stood in the corner. No one else spoke up. For one of the first times in the afternoon, the bells sat completely silent.

An invisible timer went off at the front of the room. The answer flashed up on the screen, with no one to claim it: John F. Oliven, who coined the term in a medical textbook over 50 years ago.

Another hard-to-answer question? The name of the court case that made gay marriage legal across the U.S. in 2015 (it was Obergefell v. Hodges). Or the terminology for “transgender” in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), before the medical establishment stopped referring to it as a mental illness in 2013. Or the first U.S. president to make it illegal for members of the LGBTQ+ community to work in U.S. government.

Team one guessed Ronald Reagan, whose administration bungled its response to the AIDS crisis in the 1980s. In the front row, Celentano shook her head.

“No,” she said. “I think it was earlier. I’m thinking … who was before the first Bush?“

The answer—Dwight D. Eisenhower—hadn’t been a name that anyone was prepared to give.

“Please Don’t Make It A Big Deal”

As one group wrapped up jeopardy, students facilitating a peer-led “coming out” workshop jogged up to the front of the room. Motioning to two balls of rainbow yarn in the corner of the room, they described an icebreaker in which participants answer a series of yes or no questions, collecting strings of yarn for each time they agree. At the end, the hope is that they can look around the room and see ”how much we have in common” with other participants.

The group also plans to open the floor to personal coming out stories, for students who want to tell theirs, or ask questions they may not be able to at home or in their schools. Cable jumped in first, recalling how when he came out to his mom as trans, “she was like, no.”

That was also the reaction his sister had. And the one his dad had. For a while. And then this year on Valentine’s Day, he got a card from his dad addressed to “Houston.” He noticed that his sister uses his chosen name and pronouns more often. “So things are getting better,” he said.

Then Danielle Botta stepped forward to practice, “because I want to do it without crying.” Earlier in the afternoon, she had come in smiling, joking about how one tweet had turned her into a viral sensation for a few hours. Now she took a deep breath.

Botta described a childhood growing up in Naugatuck, where people didn’t talk about sexuality very much, and sometimes used homophobic language when they did. By the time she was on the cusp of high school, she had decided not to come out until she was in college.

“I’m like, I’m just gonna wait,” she recalled. “I’m like Love Simon.”

Then she arrived at Co-Op, and sensed that the student body might be different than it was at her previous school. An assignment from Vollano, sculpted around a personal essay, turned into a chance for her to come out to her class. She said it was one of the most empowering and scary experiences of her life. She apologized for getting choked up.

“It’s okay to show your emotion,” offered Celentano. “Because coming out is terrifying.”

“What advice do you have for allies?” asked Wuzzardo from one side of the room.

“Please don’t make it a big deal,” said Bell. “When we come out, we’re looking at everything. When you say ‘I didn’t know you were gay!’ that affects us so terribly. Even if you don’t mean it in a certain way.”

“Or with body language,” Cable jumped in. “We notice everything. When you shudder, we notice.”

“Does it help if that person apologizes?” asked Wuzzardo. Murmurs of agreement sprang up around the room.

“Yes!” said Botta. “But it’s helpful to remember, for that person, that they don’t have to forgive you right away.”