Bregamos Community Theater | Culture & Community | Fair Haven | Frances "Bitsie" Clark | Arts & Culture

Frances "Bitsie" Clark, who turned 92 on Oct. 30. Lucy Gellman Photo.

It was as if someone had flipped a switch. At the front of the stage, Bitsie Clark rose from her chair, cupped both hands around her mouth, and gazed across the theater, where a portrait of the late Satchel Ramos looked back with wide, soft eyes and peach fuzz over his top lip. On cue, some 200 eyes turned toward the stage. Conversations quieted to a hush. It was time to celebrate an arts giant in the heart of a city she helped transform.

Amidst tear-flecked tributes, artist testimonials, tidbits of New Haven history and at least three different renditions of “Happy Birthday,” it marked a fitting start to Frances “Bitsie” Clark’s 92nd birthday year, held last Monday at Bregamos Community Theater in Fair Haven. Over two hours, friends, family, and a parade of creatives and former colleagues fêted Clark’s legacy in New Haven, where she has for decades nurtured a creative ecosystem that is still alive and growing today.

Throughout, friends and colleagues honored her legacy as a rare and gifted bridge-builder, who worked through New Haven’s long and sticky history of de facto segregation to celebrate all of its artists. She’s still at it: the event doubled as a chance to honor artists Linda Vauters Mickens and Jeff Ostergren, who are the 2023 grant recipients of the Bitsie Clark Fund for Artists.

Both received $5,000 to dedicate to new projects, from a life-sized commemoration of New Orleans’ vaunted second line to an exploration of art, advertising, and pharmaceutical taboos. More on that below.

Top: Stacy Graham-Hunt, who is a member of the fund's advisory committee, and author Rebekah Fraser. Bottom: Linda Mickens and Bitsie Clark.

“This is amazing to me!” said Clark, who spent the evening in a chair on the stage, receiving a steady stream of people who stopped by to say hello, some crouching by her side with memories that stretched well into the evening. “I didn’t expect any of this–I’ve seen people tonight that I haven’t seen since the 1970s. What I’ve begun to think is when you get into your 90s, you’re a different person.”

From the moment Monday night’s festivities began, attendees captured a spirit of awe and delight that Clark herself, who moved to New Haven in 1956, has brought to the city as a nonprofit leader, arts champion, elected official and beloved community fixture. Speaking early in the evening, Bregamos Community Theater founder Rafael Ramos remembered meeting Clark two decades ago, well before the theater secured its brick-and-mortar home on Blatchley Avenue.

It was the early 2000s, and Ramos was by day a dogged housing code enforcement officer for the city. Outside of work, he had just started building Bregamos and Big Turtle Village, a nature immersion program for New Haven kids that has since served hundreds of young people. In the camp’s second year, he hit a wall: the program ran out of money. After hearing about the program, Clark brought Ramos to meet Bill Graustein, who became one of its earliest supporters.

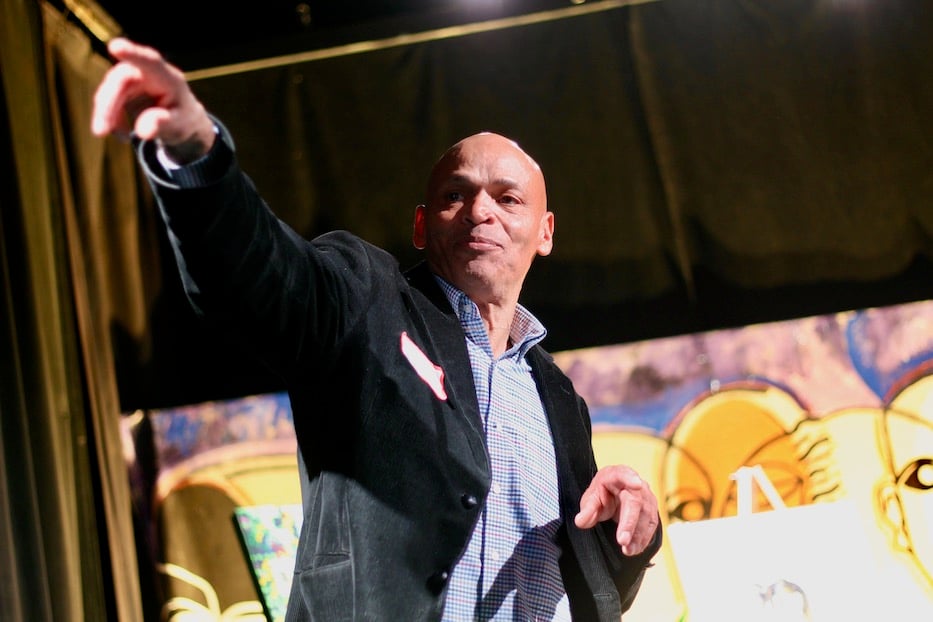

Rafael Ramos: “I love her, really. She’s like the goddess of the arts."

“She was just very in touch with what we were doing in Fair Haven,” he recalled before taking a seat at the congas, and playing a rousing, heartbeat-like version of “Happy Birthday” to which the audience joined in. “Bitsie was always encouraging, supporting, pushing you to take the next step.”

Ramos has remained close with Clark ever since. When he secured a space for the theater in 2007, Clark was there to introduce him to poet and playwright Aaron Jafferis, who was working on a hip-hop musical about the Latin Kings that the two brought to the neighborhood, and later to an arts festival in Rotterdam. In 2014, she watched Ramos plan and run his first annual “Art from the Heart Festival,” held in honor of his son, Satchel. She never stopped visiting the space or checking in on Ramos. He loved that about her.

“I love her, really. She’s like the goddess of the arts,” he said, something catching in his throat. At the 2014 festival, she received an award for her work that Ramos lost, and then found again this year. He presented her with it anew on Monday night.

Top: Vocalist Thabisa Rich. Bottom: Steve Driffin and Bitsie Clark.

Playwright Steve Driffin, who was one of the fund’s 2021 awardees, thanked Clark not only for her present support of New Haven’s arts landscape and artists, but for her role as a longtime mover and shaker in the city. In the 1990s, it was Clark, then executive director of the Arts Council of Greater New Haven, who ensured that his work Yo’ Street saw a full run at James Hillhouse High School. The two have kept tabs on each other since.

“When I got that award, I thought I had won, like, an Oscar,” Driffin said of the grant to laughs that undulated across the room. With the funding, he was able to finish and stage his work Death By 1,000 Cuts: A Requiem for Black and Brown Men, which has since traveled to New York for an Off-Broadway premiere. “It meant a lot to me.”

She’s also been one of his most consistent cheerleaders. When Driffin was debuting Death By 1,000 cuts, which was a decade in the making, it was Clark who reminded him of the grace and power of which he was capable as a writer.

“You looked at me and said, ‘What? Don’t be nervous,’” he remembered, tears forming in his eyes as he beamed at Clark. When he thinks about those who are most dear to him (his acronym for it is LIFE, or Loving Intimate Friends Eternally), she is always in that constellation of people. “I thank you not [just] for the confirmation, but for the inspiration.”

This year, Driffin also helped screen applicants for the award, which reminded him that “there is a lot of talent in this city,” and more artists who are deserving of dollars than those who receive them. While it was painstaking work, he said, it was well worth it for the woman it was honoring. He, like many throughout the night, also praised the work that Mickens and Ostergren will be bringing to the city with their grant funding.

Before a Mozart-inspired cover of “Happy Birthday” on the flute (a nod to Harold Shapiro, a photographer and flutist who was also a 2019 grantee) and enough miniature chocolate cupcakes to feed a small army, both Mickens and Ostergren spoke about their forthcoming projects, and the role that direct, unrestricted funding support has played for both of them.

Mickens, whose recent work on display at Creative Arts Workshop and the Ely Center of Contemporary Art has addressed the centuries-deep trauma of enslavement, white supremacy and police brutality, will be focusing on a life-sized rendering of New Orleans’ Second Line, a neighborhood tradition brought to the bayou by enslaved Africans, and preserved for centuries as a way to commemorate births, deaths, and liminal life moments.

Mickens said she has been thinking about the project since the 1980s, when her work as a travel nurse brought her to New Orleans for the first time. For three years, she lived in New Orleans’ Warehouse District, soaking in the culture as often as she could. She went on to work as a healer and healthcare worker for decades, including in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Events like the Second Line feed her soul.

Top: Arts Council Executive Director Hope Chàvez. Bottom: Betty Monz, who was one of the women who helped launch the fund.

“To see all that energy was amazing,” she said. “It’s a whole party going around the neighborhood.”

Inspired by a rendering from the 1980s, Mickens’ work will feature five to six life-sized dancers and musicians, all of them sculpted in the paper and mixed media for which her oeuvre has become recognizable in New Haven and Hamden. While the work is still firmly rooted in the African diaspora, this project moves from the pain and heartbreak of white supremacy to the joy and resiliency of Black creativity across decades.

“It gives me a chance to do some fun stuff,” she said with a smile, adding that she believes in an “art spirit” who helps guide her along the way. “It’s a little lighter instead of focusing on world events. I think it’s [my work is] necessary, but you need a break from it.”

Ostergren, who called the funding “such a rare gift,” will be building on his interest in pharmaceuticals and color with “Reverse Engineering the Un-Advertised,” creating unsanctioned advertisements for drugs that still come with a stigma. For years, he has been inspired by the connection between synthetic drugs, synthetic paint, and Impressionism, he explained—and will now be able to take his exploration to an entirely new level.

Jeff Ostergren: "How would that change the landscape in this country?”

These new works, Ostergren said Monday, are inspired by drugs that are on the market but rarely receive splashy advertising copy because of the social taboos still attached to them. For example, mifepristone and misoprostol, which are (ideally) used together for non-surgical abortion in the first trimester. In a post-Roe America, they are the easiest and most non-invasive way to access early abortion care. And yet, they aren’t widely advertised in the public eye; a lot of discourse around them happens in secret.

“I’m interested in sort of taking these drugs and reframing it,” he said. “Saying: What if we looked at these ads as something that are everywhere? Maybe they’re good, maybe they’re bad, but what if there were works freely advertising the abortion pill? How would that change the landscape in this country?”

With the funding, Ostergren plans to collaborate with graphic designers to “create ads that look like legitimate ads,” meaning that they don’t include any sort of cheeky humor or irony, and are intended to feel exactly like real, pharmaceutical advertisements. Ostergren will then take those designs, and transform them into paintings.

“It adds an additional step in there, but I think it engages me a little more with the material, but also then kind of can reflect … into these drugs, the role they play in society, and how they’re chosen to be made visual and how they’re not visualized. So it’s a really exciting opportunity for me to have these resources and to be able to have this support.”

From the stage, that gratitude seemed to spill over and flow out into the audience, meted out in flute solos, fragrant cupcakes, rounds and rounds of applause, warm laughter, and a room that was rarely quiet in its praise of Clark’s career. There was good reason: at 92, Clark herself has continued to give back to the arts in New Haven and the surrounding region (read about fellow Bitsie Fund awardees here, here, here, and here).

It follows seven decades of giving back, from her work at the Arts Council to her time as a public servant serving downtown on the New Haven Board of Alders. After moving to the Elm City after college, Clark became a nonprofit administrator quite by accident, through a mix of necessity, skill-building, and a kind of moxie that she still carries with her in everything she does.

When she moved to New Haven in 1956, the only job Clark could find was with the Girl Scouts of America, then serving a whopping 28,000 girls in the greater New Haven region. Working under their executive director, she trained a small army of volunteers who helped the organization run. “It was booming,” she recalled Monday. “I was learning a skill that I could do in every single job.”

In the 1960s, Clark stepped back from the workplace temporarily to raise her children, a son named Jonathan and a daughter named Mary. Around her, the city’s arts landscape was changing, including a then-volunteer-led Arts Council that was just starting to figure out its place. When a divorce forced her back into the workplace in 1982, developer Newt Schenck brought her onboard as the Audubon Arts District was just starting to take shape. She remained at the helm, growing the organization in ways that no director has replicated since, for two decades.

Her memories of New Haven at that time still delight her constantly, she said. In the late 1990s, she received an award from the Greater New Haven Chamber of Commerce, then among only a handful of women to hold the distinction. After an introduction from the historian and curator Frank Mitchell, she asked Jafferis to perform a rap in her honor. Members of the Chamber, then almost entirely white and male, had to pick their jaws up off the floor.

Her love of the arts, and of the city, is also one of the things that has kept her so involved. After her time at the Arts Council, Clark worked as a consultant for several years, then At 79 years old in 2010, she took her last job at HomeHaven, designed to engage elder New Haveners through programming and activities. As the organization’s executive director, she grew HomeHaven’s footprint, taking seniors on one particularly memorable trip to the Broadway musical Hamilton in 2016.

In 2017, Clark left HomeHaven and moved into the Whitney Center in Hamden, where Driffin brought Death By 1,000 Cuts for an intimate and revelatory performance last year. Now, she said, “I spend all my time reading,” from a biography of Winston Churchill to Walter Isaacson’s new read on Elon Musk. Except, of course, at the end of every October, when she has a birthday party.

Something about 92 hits differently, she added. More people showed up than she’d ever expected. It was a chance to play the role of bridge builder once more: many of Monday’s attendees had never been to Bregamos.

“It’s amazing,” she said multiple times throughout the evening.”

The fund, like its namesake, shows no sign of stopping. Since its launch in 2018, a total of 135 donors have raised a cumulative $400,000, creating a fund healthy and robust enough to “operate in perpetuity in Bitsie’s name,” said Maryann Ott.

Six years ago, Ott was one of the fund’s founding members alongside Mimsie Coleman, Robin Golden, Barbara Lamb and Betty Monz. It now operates with a community advisory board that also includes Stacy Graham-Hunt, Kim Futrell and John Motley.

“Thank you to all of you in this room,” Ott said, and the words felt warm from the stage. “You love the arts. You love artists. And you love Bitsie.”