East Rock | Feminism | Arts & Culture | Nasty Women New Haven | Visual Arts

| Luciana McClure: "How do we talk about protest? How do we support each others' acts of resistance? How do we build a better community with that?” Lucy Gellman Photos. |

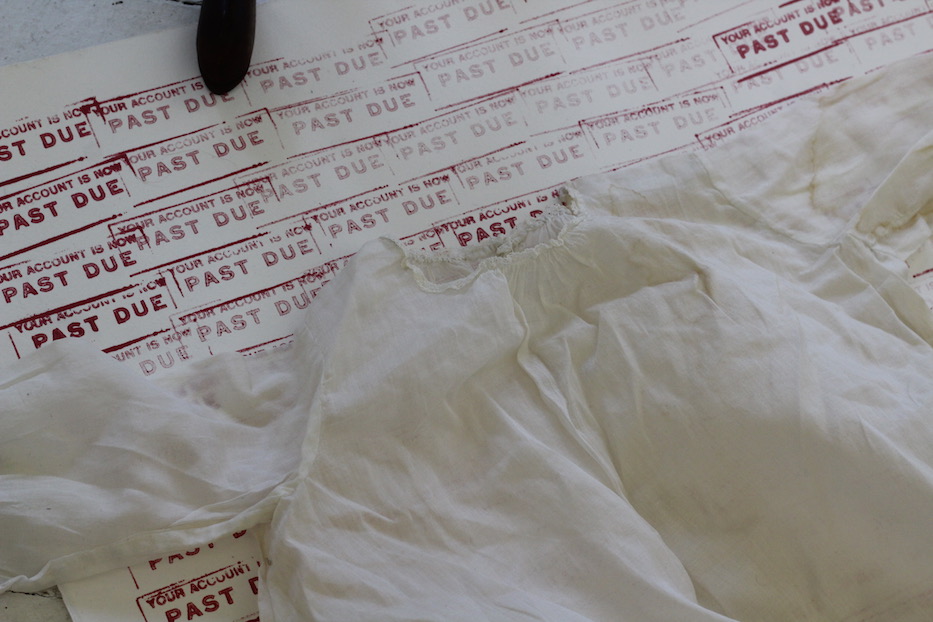

Luciana McClure lifted a small hammer and looked around the The Urban Collective. A gilded vulva winked back from a series of photographs, as if it were playing hide and seek. A tiny figure shrouded in black looked over a child’s white cotton gown and length of paper stamped with the words “Past Due.” A foam finger sat at the ready with the words “Thank God For Abortion.” McClure wiggled the hammer from side to side.

“I’m smashing the patriarchy,” she laughed. “See? Bit by bit.”

McClure is the mastermind behind Rituals of Resistance, the fourth annual exhibition from Nasty Women Connecticut. As it opens on March 8—International Women’s Day—it is returning to its roots to look at how protest has evolved since the 2016 election of Donald Trump as the 45th president of the United States.

The full curatorial team includes Attallah Sheppard, Louisa De Cossy, Sarah Fritchey, Sha McAllister, and Julie Graves Krishnaswami. The exhibition runs through April 8 at The Urban Collective, nestled in the Marlinworks Building on Willow Street. It features 118 artists from over five states.

“Increasingly, we've been dealing with protest not only at a national level but also at a local level,” McClure said Monday, in the midst of installing work with artist-volunteers Robin Green and Brita DeMars. “When you look around the room, you are seeing the ways people are thinking about how they apply protest to their daily practice.”

| Detail, Aly Maderson Quinlog's Past Due. |

Nasty Women Connecticut was born four years ago, after the 2016 election and 2017 inauguration of Donald Trump gave birth to national women’s marches, small- and large-scale protests, and tens of thousands of “pussy hats” that were as well-loved as they were much maligned. The name is a reference to the third and final 2016 presidential debate, in which Trump called Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton “a nasty woman.”

Since its beginnings in a space owned by the Institute Library, the show has jumped from downtown New Haven to the Ely Center of Contemporary Art and Yale Divinity School to the edge of East Rock. Along the way, McClure had her own crash course in intersectional feminism, including the realization that Black and Latinx women and LGBTQ+ voices in the arts are still frequently passed over for cisgender, straight white women.

| Thank God For Abortion was first launched in 2015 by the multimedia artist Viva Ruiz. Information about the group's work is on view at the exhibition. Mateo Gutiérrez' mixed media And I Feel Fine is pictured in the background. |

She’s spent the past years learning through collaborations with Black Lives Matter New Haven and the New Haven Pride Center, as well as from authors like adrienne maree brown and Tricia Hersey, founder of The Nap Ministry.

"Rest, self-care, pleasure … all of these are forms of resistance," she said. "We don't understand enough about the different ways that we protest, the different ways that we resist. I think when we're using arts, we're able to understand what is at the root of each individual act of protest and resistance.”

Now, the walls at The Urban Collective teem with art, works chattering with each other across time and space. Around the room, tens of photographs document resistance in the streets, from the 2017 Women’s March on Washington to Catalan protesters in the streets of Barcelona last fall. Close to the entrance, McClure has hung three pieces in a wash of blue around artist Ricky Mestre’s commemoration of the Stonewall Riots, in part a tribute to the Black transgender activist Marsha P. Johnson.

On an opposite wall, viewers are greeted with Mateo Gutiérrez mixed media And I Feel Fine (US-Mexico border & El Paso Texas), a huge multimedia piece where acrylic paint, color pencil, and pastel fuse to meet glossy, bright embroidery and thick thread. Come close enough to the piece, and the embroidery is its own work within a work, strands overlapping to form cheeks and hands.

| Detail, Mateo Gutiérrez' mixed media And I Feel Fine (US-Mexico border & El Paso Texas). Clinard's work is pictured in the background. |

At a distance, the piece unfolds in two horrifying vignettes, both ripped from the headlines. On the left, a mother stoops down to comfort her son, eyes shielded and facing the ground. From the crook of her arm, he looks off to the side, to something one can’t see beyond the frame. Both are so small and so weary as the background swells around them like it might swallow them up.

If the image looks familiar, it’s because it is: the mother is real-life Guatemalan migrant Lety Pérez, holding her son Anthony. The two were stopped by a member of the Mexican National Guard when they attempted to cross into the United States from Mexico last year.

To their right, Gutiérrez has recreated a scene from the 2019 shooting at a Wal-Mart in El Paso, Tex. Last year, the shooting was an act of domestic terrorism fueled by anti-immigrant sentiment that took place just days after Reuters’ Jose Luis Gonzalez wrote of Pérez' plight at the border. As they stumble forward in the daylight, a man clutches a semiautomatic rifle, its long face turned toward the pavement. Beside him, a woman opens her mouth and howls.

In literally stitching the events together, Gutiérrez delivers a powerful statement on how commonplace xenophobia, overt structural racism, and the use of military-grade force have become under the current administration. The title evokes R.E.M.’s 1987 song of the same title, with the lyrics It’s the end of the world as we know it/And I feel fine.

| At right, Yali Romagoza performs as Cuquita The Cuban Doll in Meditating my way out of Capitalism and Communism. 12410 days of Isolation. Left, Susan Clinard's Politics of the Female Body. The work is intended to be seen from multiple angles. |

Nearby, artist Yali Romagoza performs as Cuquita The Cuban Doll in Meditating my way out of Capitalism and Communism. 12410 days of Isolation, a video installation that uses a mix of rest, personal interventions on the built environment, and tongue-in-cheek humor as a form of resistance.

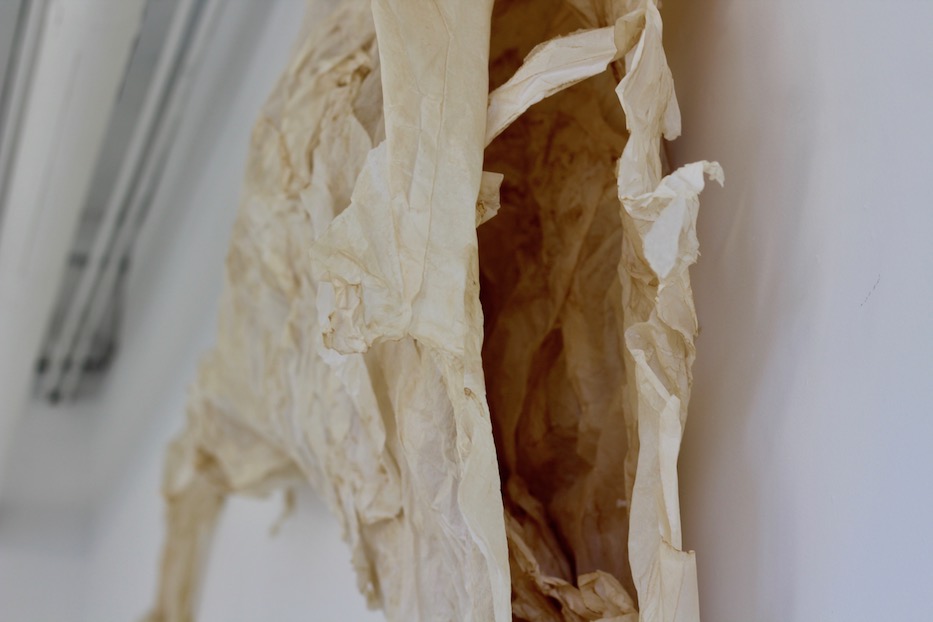

Several of the pieces in the show are open to interpretation. In one corner, tiny puppet shapes spin slowly on a lighted carousel from artist Kimberly Van Aelst, trapped inside a cage as they turn. In another, a limp female body from sculptor Susan Clinard slides to the floor.

Her legs and arms are raw and twisted as if they’re exposed muscle; her back sits upright and flat on an ironing board. On her calves, where skin and hair should be, small black irons weigh everything down. The head seems too heavy for her body and shoulders.

If she is wounded herself, she also wounds: it is almost impossible to look at not feel surges of despair, empathy, physical pain, and anger.

| Detail, Isabella Sarceri’s Reach. |

This is how a mini-world unfolds, pulsing with resistance. On a long wall towards the back of the collective, viewers encounter Isabella Sarceri’s Reach, what looks like a huge paper uterus installed sideways. Across the wall, the fallopian tubes trail like tentacles instead of standing up like little arms. Like Gutiérrez’ work, the piece invites its viewers to explore from all angles: the mouth appears ready to engulf viewers, and marks the body as both beautiful and alien.

On a bench across the room, Zohra Rawling’s porcelain I, Atoraya seems like a quiet gesture, full of life the closer one gets to it. A face looks out beneath an Assryian headdress, surrounded by nods to Rawling’s own Assyrian heritage: cleanly sliced pomegranates, grapes and grape leaves, and a small lamassu near the base. A trail of gold paint, so smooth it seems like liquid, runs from a crack at her face to the base. Something, she seems to say, is horribly broken.

| Detail, Zohra Rawling’s porcelain I, Atoraya. |

Others artists have turned the concepts of protest on their heads, engaging the politics of militarism as they go. Toward the back of the room, Brita DeMars’ The Gospel of Mona stops viewers in their tracks as a huge, plush fist rises toward the ceiling. At the top of the fist, a yellow-nailed middle finger sticks up in protest.

At the base, chapter titles from Mona Eltahawy’s The Seven Necessary Sins for Women and Girls appear in big, plush words. An anarchist A, rendered in white paint and glitter, winks out at the wrist.

At the back windows, three breastplates from artist and designer Jennifer Rae wink out, hands reaching for each other and dangling in space across their surfaces. The longer one looks, the more associations unfold: epic warfare reserved for The Iliad and The Odyssey, but also the canonical Creation of Man, ripped from its place in history and placed knowingly among uteri and vulvas.

| Work by Jennifer Rae and Karen Ponzio is installed at the back of the collective. |

But this is not an embrace of male customs or creation (think Orlan’s L’origine de la Guerre, but with room for imagination). The shields have been set at rest. In the hands, there’s something sublime and graceful, as if a spiritual balm has been applied. Almost on cue, a banner painted with the word NO in black winks out from the far corner of the room.

The discussion, which happens almost entirely among the artworks, is also meant to be intergenerational. Artists range from 20-year-old Carly Julius to 81-year-old Janet Braun Reinitz, with every stage of life in between. As it opens this weekend, McClure and other members of the curatorial team are thinking about where Nasty Women goes after this year, whatever the result of the next presidential election may be.

With support from her co-curators and the Feminist Art Coalition (FAC), McClure is working with the Institute of Sacred Music at Yale to curate an event in the fall. Before the election in November, she will also be holding Witch Hunt, a one-night exhibition urging viewers to think about their role in politics. Nasty Women Connecticut has a show lined up at the Lyman Allyn Museum in the spring of 2021 that pulls together work from all four exhibitions.

| Artists Cheryl Morgan and Scott Lewis install photographs taken last year, as Catalan independence activists protested in Barcelona. Hundreds of activists are still in prison. |

“Whether we ever thought this was gonna happen or not, we have carved a space for ourselves, and for New Haven, in the feminist timeline,” she said.

At the same time, she added, she is also focusing on the rituals of resistance that are keeping this year’s artists afloat. When the show opens this weekend, it will be with spoken word, song and poetry from the New York-based Mahina Movement, as well as a large celebration of four years of collective protest through art.

“We’ve made it through these four years,” she said. “This work is about how we are impacting our community directly. It's understanding: how do we talk about protest? How do we support each others' acts of resistance? How do we build a better community with that?”

Nasty Women Connecticut’s fourth annual exhibition, Rituals of Resistance, opens March 8 with a reception and performance from 4-6 p.m. at The Urban Collective, 85 Willow St. in New Haven. For more information, click here.