East Rock | Ely Center of Contemporary Art | Politics | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | COVID-19

| Kelsey Miller, Everyday People. Site-specific installation at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art. Now runs through Nov. 15 at the Trumbull Street space. Lucy Gellman Photos; all work by artists. |

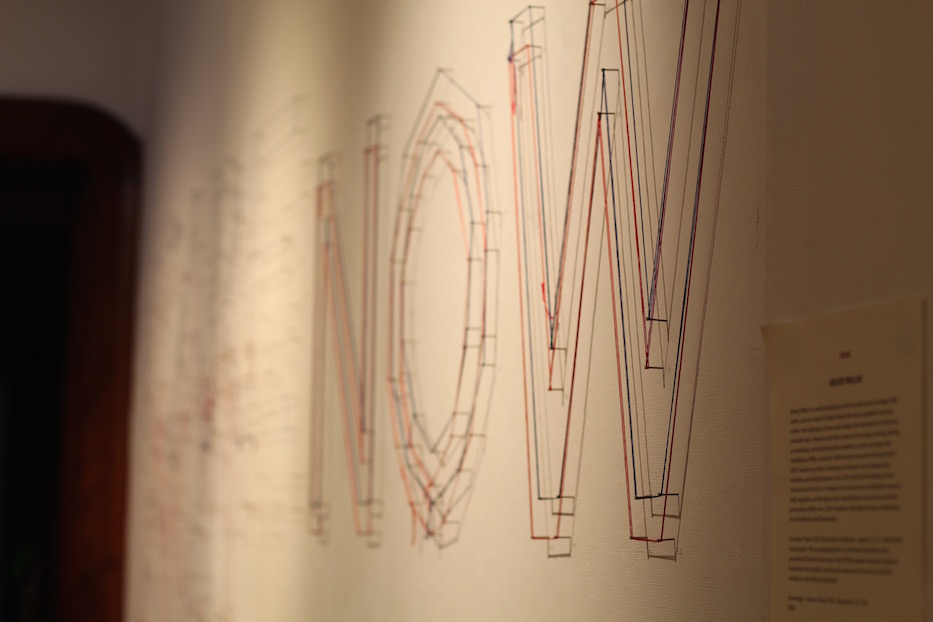

The threads are pulled tight, overlapping in red and blue against a white wall. From one nail, they run to the next, propelled by a timeline that is detailed below. Breonna Taylor is murdered in Kentucky, and a red strand wraps around a nail. Wildfires explode across the West and a thread is cast across to form a taut, straight line. Over six and a half million people apply for unemployment in the U.S., and somehow the thread keeps going.

Only when a viewer steps away can they see what the pattern spells out: Care. Act. Now.

Kelsey Miller’s Everyday People sits at the heart of Now, one of two new exhibitions at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art (ECoCA) running through Nov. 15. An extension of the center’s virtual show What Now? earlier this year, Now takes on the present moment with references to the novel coronavirus, a parallel epidemic of white supremacy, and nods to the upcoming election. It includes both indoor and outdoor installations, with work by 17 artists spread across the center’s two floors and front and back yards.

“This year has been and continues to be a turbulent and uncertain one,” wrote curator and artist Margaret Roleke, whose work is also featured in the show. “COVID-19 has entered our lives and turned everything upside down. Isolation, illness and too much togetherness has strained families and relationships. Add to all this an inept leader and police violence against people of color. Marches and protests against racism have finally started to get a dialogue going on systemic racism in this country.”

| Top: Cindy Tower's Protest Pile. Bottom: Donna Maria de Creeft and Sara Jane Munford's Slow the Spread. |

What she does not mention, at least not explicitly, is that those dialogues are only new among white people: Black and Indigenous folks have been talking about systemic racism in this country for over 400 years. It follows, then, that Now’s strongest works are those that document the past seven months with a clear-cut sense of history rather than self-pity, overwrought statement making, or heavy-handed opining.

Stepping into the center’s architectural core—a wood-paneled space where receptions once featured hundreds of people, shared finger food and a DJ—Leigh Busby’s photographs stop a viewer in their tracks. Taken from months of protests, they document a city grappling with racism in its streets, public parks, and nearby towns. In greyscale, they pop against the oxblood-colored walls, telling a story of a New Haven’s recent past that can inform its present.

They also bear witness to protest during COVID-19, where faces hidden beneath masks, gaiters and bandanas are suddenly the rule, and not the exception.

Several of the images come from late June, when the statue of Christopher Columbus was removed from Wooster Square in a seven-hour standoff between protesters, police, and white supremacists. In one, pro-removal protesters gather in a circle, raising their arms and clenched fists in a gesture of solidarity and Black power. Their heads are down; it appears they are frozen in some sort of benediction. At the right hand corner, a cluster of mostly white press photographers presses in, interlopers in the space. Busby remains on the periphery, camera in hand.

| Top: Installation view of two of Busby's photos. Bottom: Detail of Denise King-Ashley’s Crossroads. |

In another, a knot of police works to separate crowds, forming a half-hearted barrier between all-white pro-Columbus protesters and the activists who showed up to counter them.

Busby—whose photograph of Columbus dangling from a harness stunned viewers earlier this year—captures a protester as she steps forward, mask down and mouth open. Faces rise behind her, angry and concerned. Eyes blaze. There’s no judgement there, just the moment. Viewers are left to draw their own conclusions.

In yet another, Busby transports viewers to a protest during which activists in Hamden shut down the Wilbur Cross Parkway in early June, two weeks after George Floyd was murdered by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. In the photograph, activist Laurie Sweet holds a poster that reads “He Called Out MAMA, So I’m Here.” The photograph is a reference to Floyd, who pleaded for his mother as Chauvin knelt on his neck and ended his life.

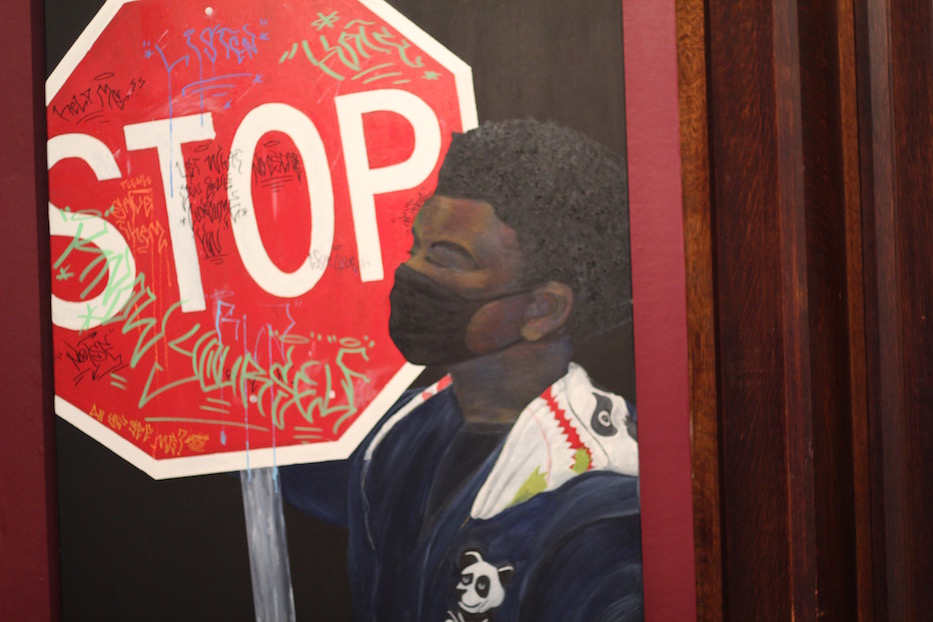

The photographs feel right alongside Denise King-Ashley’s Crossroads, a portrait of a young Black man standing beside a stop sign, one arm curled around it as the other hangs down. He is still baby-faced and innocent: his hair gathers in tight black curls around his head while a panda peeks out from his sleek blue sweatshirt. While the work was originally completed before COVID-19, it appears to have been updated: he wears a simple cloth mask, standing at a crossroads of two parallel, interlocking pandemics.

| Top: Detail of Howard El-Yasin's site-specific installation BLACK IS on the second floor. Bottom: Detail of Martha Lewis' work on the first floor. |

The room works as a sort of interstitial space, suspended between past and future, known and still unknown. To one side, galleries filled with work from Now and the concurrent USPS Art Project beckon like spokes to a central hub. Against a wall, a winding staircase leads to more art upstairs.

An open back door sits just meters away, showing viewers out to where the exhibition continues outside. Over it all, a looped video installation from Gone With the Wind plays loudly, the sound pausing for a tick-tick-ticking from Howard El-Yasin’s installation BLACK IS upstairs. It seems like there is a grandfather clock hidden away, about to jump out at any moment.

It also works as a framing device. On the house’s front windows, David Borawski has designed a sort of American flag meets caution tape meets vinyl installation, managing to articulate how synonymous patriotism, bigotry, obfuscation and state-sanctioned violence have become with each other in four years. Just one room over, Miller’s Everyday People requires a close read, showing how a series of national, interlocking crises can result in a sense of total, unbridled catastrophe.

If the site-specific installation doesn’t spell it out, her Knowledge + Action = Power does as it states “Know Your Ballot/Cast Your Ballot” in clean letterpress.

In the back of the building, the show continues with work that wraps around trees, hangs from windows, builds impromptu woodpiles and rises from the ground as if it has always been waiting there. Roleke’s curatorial eye is sharp: her own cyanotype Danger/Peligro sits across the yard from Laura Marsh’s Broken Situations banner, placing the two immediately in conversation with each other. They seem to whisper back and forth, acutely aware of every work inside, and the struggle all of them are facing.

Between them in the grass, a mismatched assemblage of bones from Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez makes a brain do mental gymnastics. Surely, a viewer thinks, this is just a puzzle for which they need to figure out the correct order. But the longer they look, the faster an image does emerge: long, interlocking bones, that don’t amount to any single skeleton that one can see.

| Margaret Roleke's large cyanotype Danger/Peligro sits across the yard from Laura Marsh’s Broken Situations banner. |

The USPS Art Project, which includes hundreds of pieces of mail art, feels like part of the same whole. The exhibition is a local chapter of Christina Massey’s initiative of the same name, which began earlier this year when the artist was quarantined in New York in April. Massey began with a simple set of directions: find a partner, start an artwork, mail it to them, and let them finish it. After sharing the project on social media, she has seen over 600 pieces of mail art come in.

“It just felt like, how can we as artists improve our value?” Massey recalled in a recent phone interview. “We could make masks, but then they were saying that you couldn’t give homemade masks to hospitals. And then, I thought: ‘Oh. This is what we can do.’ We can help by just making our work.”

Installed salon-style on the Ely Center’s walls, pieces pull a viewer in with bright color, witty design, and media that extends into collage, embroidery, fabric and sculpture. Some artists have riffed on postage stamps, envelopes or letterboxes themselves; others have kept it to postcards and paper.

A four-part design in an upstairs gallery (pictured below), for instance, might pass for a politely patterned postcard if a viewer does not take the time to look closer, and study a delicate interplay of color, collaged elements and printed matter. It is worth the closer look, just as is Donna Maria de Creeft and Sara Jane Munford’s rust-colored, layered Slow the Spread one gallery over.

| Top: Millen Umoh and May Nasiri’s Affranchissement. |

Some pieces are punchy. In Millen Umoh and May Nasiri’s Affranchissement, the artists have put a design to the definition of manumission, the act of freeing people from enslavement. In the work—which looks like a huge U.S. postage stamp—three women swivel in profile, their headwraps and garments made of used stamps celebrating Monticello, George Washington, SEATO (the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization) and the United Nations among others.

The act of wearing the stamps is perhaps a reclamation, made complete by stars and stripes that acknowledge COVID-19, wage disparity, police brutality and sexual harassment and assault.

At points, it’s not totally clear where the mission of Now ends and that of the USPS Art Project begins, which may speak to how much the two suit each other. In Dara Oshin and Robin Roi’s The Serpent In The Garden, a serpent curls its long body around a pile of eggs that look more like rocks. Weeds grow out of the ground; a huge orange sun sits low in the sky.

| Top: Dara Oshin and Robin Roi’s The Serpent In The Garden. Bottom: Susan Goethel-Campbell and Anne Gilman, The way in. |

The snake hissses as it casts one orange eyeball out at the viewer. The substrate is just as interesting: the piece is a collaboration with underpainting by Roi and the primary design by Oshin. Just meters away, Now artist Martha Lewis’ first 100 Quarantine Cinegram images play on loop, nearly the same color as Oshin’s bulbous sun.

“One thing I read was that they could appear as a spirit animal when you are stepping into the unknown and need support to move forward,” Oshin wrote on Instagram of the piece. “They are also a symbol of transformation, rebirth and healing.”

The art project has extended well beyond the boundaries of conventional mail art, in what may be a statement to how deeply some artists value the United States Postal Service—and their ability to co-create with each other.

In La Victoria vs La Sirena, Siu Wong-Camac and Patricia Espinosa have created a three-dimensional wall installation, with mixed media extending out around an image of greco-roman statues. In Why Is The Measure Of Love Loss, Diana Schmertz and Alyse Knorr have layered text with body parts, to create a soft and sensual meditation that the viewer must read up close.

“It's been amazing to see how people take the idea and run with it,” Massey said. “It was really just about connecting with people and in doing so helping the USPS, which really needed our help. Now, it's just becoming more and more crucial.”

Now and USPS Art Project both run at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art through Nov. 15. The center is following COVID-19 compliant guidelines, including mask wearing, social distancing and limited capacity at all times. Hours are Thursdays from 5-8 p.m. and Sundays from 1 to 4 p.m.