Culture & Community | Education & Youth | High School in the Community | Public art | Arts & Culture | Arts & Anti-racism

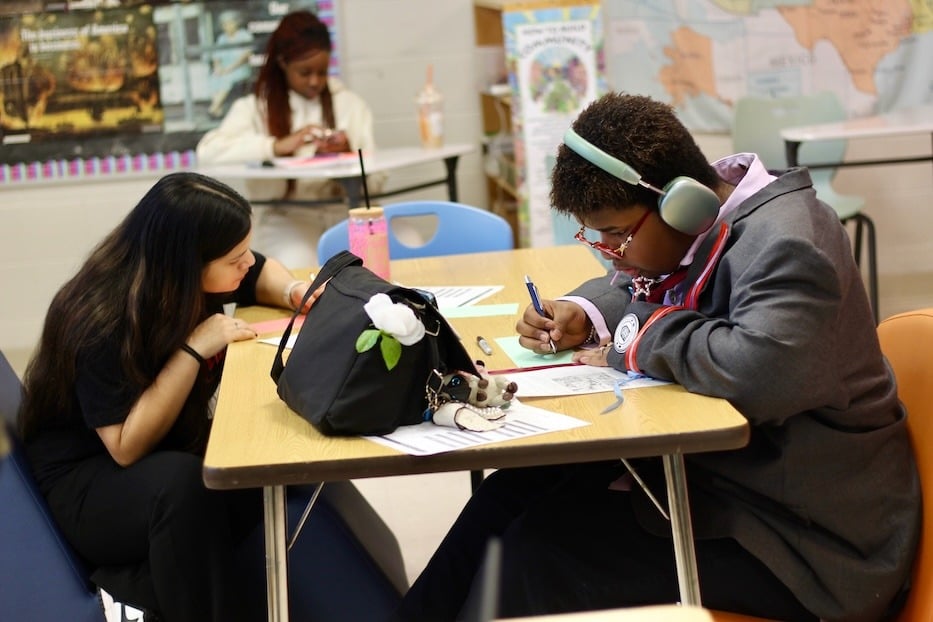

Juniors Jonaily Colón and Japhet Gonzalez. Lucy Gellman Photos.

At the front of Ben Scudder's history classroom, the year was 1898, and the United States and Puerto Rico were at a standstill. Puerto Rico, played by junior Japhet Gonzalez, wasn't thrilled about the U.S. invading the island, which had already withstood centuries of Spanish colonial rule. The U.S., played by junior Jonaily Colón, insisted that it would be an auspicious new start. Behind them, a giant map of the world covered the wall, rainbow-patterned continents jutting into an expanse of blue.

"Um, ok—are you gonna make us a state, then?" Gonzalez asked. Colón's mouth twisted uncomfortably; the U.S. hadn't expected this question.

"Mmmm, fun-ny," she said, sucking the air in between her teeth. "We haven't even considered that. Well, at least, not yet."

It's one of the ways students at High School in the Community (HSC) are bringing history to life in Scudder's section of "Black & Latinx/Puerto Rican Studies," a year-long elective that is now in its fourth year at the school. As it sprints from creation of race and racism to the Mexican-American War to protest culture across the arts, it is teaching students a history that is still often lost to dominant narrative.

In so doing, it’s also changing how they understand themselves, their city, and their country within the curriculum.

Sau'mora Short: “I feel like in each history class, you learn something you never knew.”

“I’ve never taken a class like this before,” said senior Sau'mora Short, who is one of the class’s most vocal participants. “I feel like in each history class, you learn something you never knew.” After years of learning about the same few Black Americans—usually in February—she was excited for an elective that offered a broader lens on history.

The class, multiple iterations of which Scudder has taught, grew out of years of statewide, youth-led advocacy, including from New Haven-based groups like Students for Educational Justice and Metropolitan Business Academy’s Nataliya Braginsky. In December 2020, the Connecticut State Board of Education approved the class as a high school elective, requiring that all Connecticut public high schools be ready to teach it by fall 2022.

At HSC, Scudder splits it in half, focusing heavily on Black history in the United States before making the pivot to Puerto Rico and cross-cultural solidarity movements in late March. Because “the state curriculum is a beast”—even cleaved into two semesters, it covers enough history to be a two-year course—Scudder approaches it “more like a playbook,” working through what he can while making sure that students are still learning.

He also tries to make it as interactive as possible, weaving in elements of New Haven history where he can. Earlier this year, for instance, the class attended Shining Light on Truth: New Haven, Yale, and Slavery at the New Haven Museum, learning about the city’s history of slavery and the HBCU that wasn’t all before the end of class.

On a recent morning, he took students to Wooster Square, to see the new statue that stands where a monument to Christopher Columbus came down in 2020 (“we don’t like it,” Colón said emphatically). Even a class on Puerto Rico, environmental racism and U.S. aid can feel close to home: many of his students have family members who were directly affected by Hurricane Maria. So far, nothing about his teaching has changed with the current administration.

“We haven’t had organized conversations” about recent attacks on the Department of Education and how they might affect curriculum going forward, he said. “But if this curriculum is under attack, then HSC is under attack.”

Students, meanwhile, come to the course for some version of the same reason: they’re fed up with what they’re getting (or more aptly, not getting) in their other history classes, and want to know more about who has been written out of the history. Gonzalez, for instance, knows bits and pieces of Puerto Rico through his family, members of which hail from the historic port city of Loíza.

What he craves, though, is a fuller picture of the place that his family calls home, both before and well after sixteenth-century colonization. He likes to dance, for instance, but has never formally learned about or had a chance to try la Bomba y la Plena. He visited the island once during childhood, but hasn’t been back since. When he’s able to look at a timeline or debate Puerto Rican statehood, it feels like a puzzle piece sliding into place.

Or Colón, who serves as a student representative on the New Haven Board of Education and identifies as both Puerto Rican and Dominican. Before this year, “I knew a little bit” of Puerto Rican history, but felt largely in the dark, she said. Her family speaks Spanish at home; her mom connects her to her roots through dishes that always seem to be going on the stove.

But she’s never made it to the island, which she hopes to visit one day. While her paternal grandmother is still in Ponce, she comes to the family in New Haven, instead of the family coming to her. “Taking this class has helped me learn more about my own history,” said Colón as she shaded in parts of a timeline that began in 1493, with Columbus’ second voyage.

Part of the learning happens in between worksheets and planned discussions, as students interrogate the materials—and work with each other—to better understand history. As Colón finished her timeline and rattled off her mom’s lexicon of dishes—yucca, plantains, arroz con grandules y pernil, pasteles—Gonzalez made murmurs of approval from across a cluster of desks (“You eat that too? Get out!” he said of rellenos de papa, a smile at the edges of his mouth).

They were interrupted as Scudder brought the class back to attention, lo-fi music still playing in the background. He looked from students back down to a worksheet he had handed out just minutes before. “You guys, look at this,” he said. He motioned to Short, who had been working quietly at a desk on the right side of the room for almost an hour. “Sau'mora pointed out this glaring omission.”

Scudder and students later in the day, working on a mural that is tied to Black and Latino U.S. History.

At her desk, Short read from the sheet, which introduced Puerto Rico as a land that belonged to the Indigenous Taíno people for generations, until the arrival of Juan Ponce de León in 1508. There was the sentence that had snagged her attention: In the next century, the Indigenous people were ravaged by disease.

Her face hardened a little. That one choice—the use of the passive voice—she’d seen it in history books so many times before. It took all of the blame off the European colonizers who devastated the Taíno population, from forced marriage and forced labor to the spread of diseases that the island had never seen before.

“I feel like they try to not put the blame on them,” she said. “It happens a lot. Nobody really knows that Taínos was there first,” because that’s still not how it’s taught in the mainstream.

“Right?” Scudder said, praising Short for the catch. “When you look at who is responsible, talking about Columbus and his men and the King and Queen of Spain, [they] did some pretty awful stuff. And this just completely skips over that.”

“It’s so crazy,” Short said.

“And Scene!”

Moments later, that vision for an engaged class came to life anew, as Gonzalez and Colón took their places at the front of the classroom and prepared to perform a skit about Puerto Rican statehood for the first time. Above their heads, a neat row of blue-and-red posters peeked out, as if the figures on their surfaces were looking on. A white question scrolled across a monitor between them: Why do you think the U.S. did not accept the result of Puerto Rico’s 2012 vote for statehood?

Winding the clock back to summer 1898, the two role-played the U.S. invasion of Puerto Rico, which took place during the Spanish-American War. Gonzalez, sporting a constellation of ribbons the same light blue of the nineteenth-century Puerto Rican pro-independence movement, wasn’t having it. He wanted statehood or bust.

“All right, fast forward, and scene!” Scudder said, stepping in and holding up a whiteboard with a breakdown of votes for Puerto Rican statehood a century later in 1998. “We’re 100 years later now. This is the third vote that Puerto Rico has had over 100 years about their status.”

During the 1998 vote, Scudder explained, 2.5 percent of people voted for Puerto Rico to become independent, which means that it would have status as its own country. Forty-six percent voted for statehood; 50 percent voted “none of the above,” in what pro-statehood advocates decried as close to heresy. Scudder pushed the clock forward again, to a fourth vote in 2012.

“We’re gonna vote again,” Gonzalez said with an aw shucks sort of smile. “I know, I know, but we’re shaking things up. We’re gonna ask two questions. First: do you want the current status to change? And second: What would you want the change to be?”

“Mmmm, I dunno, Puerto Rico,” Colón said. Few members of the class knew it then, but the uncertainty in her voice was actually something that sounded a little like empire, of not wanting to let go. Scudder, shuffling back to the front of the room, held up another whiteboard.

This time, he explained, 54 percent of people—a clear majority—voted against keeping Puerto Rico as an unincorporated territory of the United States, through which its citizens are recognized as Americans, but do not have voting rights. In addition, an overwhelming 61 percent of people voted that statehood should be the island's new status.

“But, there's a catch,” Scudder said. “Remember, what was the catch?” he looked up at the class.

“Twenty-seven percent didn’t vote,” Short ventured, a vocal question mark at the end of her sentence, where the inflection tipped upwards.

“It wasn’t necessarily didn’t vote,” Scudder said. He explained that following the vote, 27 percent of ballots—for any number of reasons that weren’t ever made clear—were considered invalid or left blank. That is—considered invalid by the U.S. government. That pesky use of the passive voice had crept back into the discussion. Which means Gonzalez was about to get his heart broken.

“We did it! We finally did it!” he exclaimed. “There’s a majority against the commonwealth! There’s a majority for statehood!”

“Woah, woah, woah, Puerto Rico,” Colón countered. “I’m looking over these results, and I gotta tell you, they look pretty convoluted and confusing to me. Two questions: Who does that, and what does it all mean?”

Members of the class were paying close attention now. Gonzalez looked befuddled, then upset, then injured. He moved forward through his lines, “It’s starting to feel like you’re not taking the will of our people very seriously,” he said. Colón mock gasped.

“How dare you!” she spit out, trying to hold back a smile (“Bruh, what is this corny-ass play?” she had asked Scudder before the performance, looking over the script). The class burst into applause.

Short, who had been watching and listening carefully, said that it made sense to her that the U.S. wouldn’t allow statehood. In fact, that seemed exactly like something the U.S. would do.

“It’s probably because they [the U.S. government] don’t want Puerto Rico to have statehood,” she said. “So they’re trying to find any reason not to take their results.”

Civics Outside Of the Classroom

Katelyn Wang(in red) and Johan Zongo. The two lead the Yale student group Bright Spaces, which is affiliated with Dwight Hall at Yale.

Outside on Union Street, class continued even after the period was over, as a few students joined artists Johan Zongo and Katelyn Wang of Bright Spaces, a Yale student group dedicated to both public art and public service, to work on a mural. After meeting Scudder at a New Haven Climate Movement protest, Wang and Zongo worked with HSC students in the class to design a mural for a section of wall that runs along the side of the school.

“Our goal is to literally brighten up spaces,” Zongo said, grabbing a few bottles of paint, brushes and water from where he had stored them in Scudder’s first-floor classroom. With student input, he and Wang came up with a design that included portraits of Shirley Chisholm, Sylvia Mendez, and Thurgood Marshall, as well as the school’s signature eagle, soaring above the figures in an archway.

As they painted Friday, both recalled turning to the visual arts as an outlet—Wang in San Diego and Zongo in Ghana and Burkina Faso—long before they landed at Yale. After arriving in New Haven for college, the arts were a door to New Haven. The two have brightened up Noir Vintage, learned their way around city nonprofits, and in Wang's case worked with youth at ConnCAT during their summer program.

As she welcomed students, Wang zeroed in on an image of desks—part of the mural is a classroom—that she and Zongo had traced the week before. “Let’s start on those,” she said.

Soon, students were painting, sharing a trio of brushes to give everyone a chance. Junior Justin Welch, who thought the opportunity might be fun, found himself totally immersed in the process.

“Painting is a form of relieving stress,” he said.

Junior Diana Robles, who had come to see what the hype was about, craned her neck until she could see a yellow halo around Chisholm’s face. Growing up in New Haven, “I’m really interested in how everything came to be,” she said. “It feels like a lot of this is going backward but I feel like we need to highlight the people who got us to where we are today.”

She thinks about that in her law classes—a hallmark of HSC—she added. Recently, students studied the decisions in Brown V. Board of Education and Tinker V Des Moines.

“Just one case can change so many things,” she said.