Audubon Arts | Education & Youth | Educational Center for the Arts | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | Koffee? on Audubon | Black Lives Matter | COVID-19

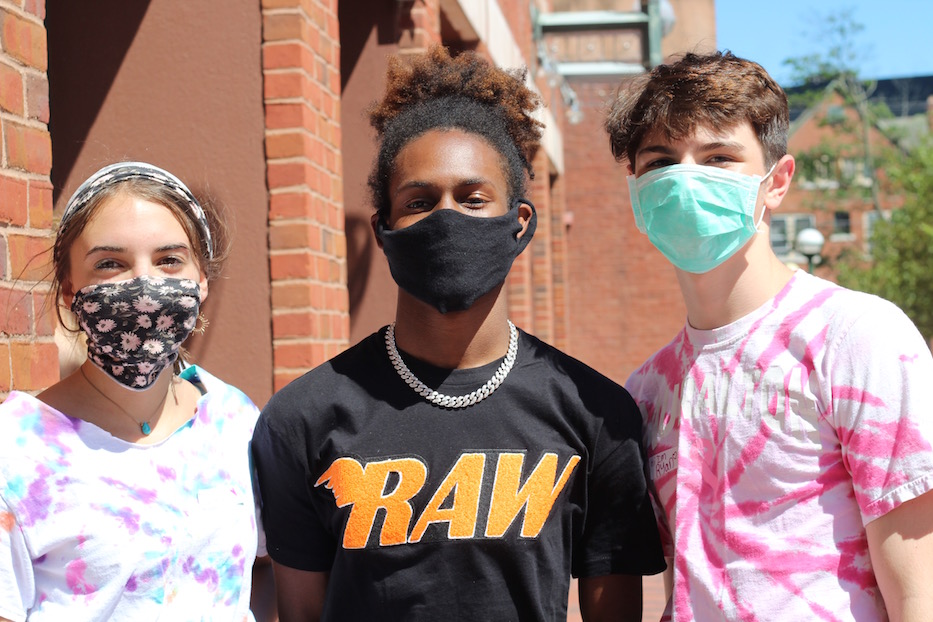

| Friends Bri Chance, Carly Hajducky, Tahj Galberth, and Cris Zunun. Chance and Galberth both graduated from ECA last year and are now students at the University of Connectivcut. Zunun is a Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School grad. Hajducky is currently a student in the music department at ECA. Lucy Gellman Photos. |

The letters sloped and slanted, bright white against the pavement. Two faces emerged, their straw-colored curls bouncing among the words, “Protect Black Trans Folks.” Tiny pink-and-blue bands stretched across their cheeks. From a nearby speaker, Bill Withers’ “Lean On Me” drifted over the street and faded into Macklemore’s “Same Love.”

The message’s author, 19-year-old Tahj Galberth, stood nearby taking in his work.

The image joined dozens Saturday afternoon, as students, parents, alumni and kids arrived to “Chalk It Out” outside the Educational Center for the Arts (ECA) and Koffee? on Audubon Street. Over four hours, the event took many forms: an understated call to action, push for intersectional coalition building, argument for defunding the police, and discussion around the lack of educators of color in the New Haven Public Schools.

The event was the brainchild of Alexis Ferreira, a rising senior at ECA and a member of the majority-white Elm City Girls’ Choir. When protests began weeks ago, she jumped on a group chat with other members of the choir, trading ideas on how to join the Black Lives Matter movement and raise money for local organizations in the social justice fight.

Protesting was out for the 17-year-old: her parents do not allow her to attend rallies or marches due to public health concerns around COVID-19. Chalking up the sidewalk, however, was fair game. While participating in the event was free, all donations went to the Connecticut Bail Fund, NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and George Floyd Memorial Fund.

“Everybody's coming together,” she said. “We are all this one human race. This is our life to live. It shouldn’t be taken away because of the color of your skin.”

In the past weeks, Ferreira said, she’s started realizing just how much she wasn’t taught about systemic racism, white supremacy, and Black history pre- and post-slavery. Ferreira grew up in East Haven’s Catholic schools, among mostly white peers.

Since protests have started, she’s been trying to educate herself and those around her. She said that in discussions with white friends, she’s been listening, and then offering counterpoints if she hears something that doesn't sit with her the right way.

“With my parents, I never really talked about this,” she said. “Because of where I live, there was never a reason to talk about that kind of thing. I was so hidden from it my whole life.”

Meanwhile, her hometown is ground zero to one of the most anti-Black and anti-Latinx police departments in the state. In 1997, East Haven cops were responsible for the killing of Malik Jones, a Black teenager whose death fueled the decades-long battle for a civilian review board in New Haven. A decade later, the department became the subject of a federal probe into wide-ranging civil rights offenses, including sustained harassment and assault of Latinx city residents.

| Alexis Ferreira, Jelin Hinton, and Ryan Piccerillo. |

As she spoke, other students turned the pavement into an explosion of color. James Baldwin’s words—“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced”—appeared in white, blue, yellow and pink chalk on a Lincoln Street driveway.

A raised, purple fist materialized on the side of Koffee? across the street. Huge, multicolored circles read “Rise Up!” and “Black Lives Have Always Mattered,” set to a crackling soundtrack that included Stevie Wonder, Bill Withers, and Andra Day. On a nearby brick wall, a few students found a shaded patch and began to write the names of Black lives lost at the hands of law enforcement, including in the state of Connecticut.

Amara Greenshpun, a rising junior studying music at the school, said she’d turned out to both support Ferreira’s effort and advocate for defunding the police. As she learns more about how the police are funded in her home of New Haven—this year the department received $43 million in the finalized city budget—she has found more reasons for that money to go into schools instead.

“We spend millions funding them when that money could be going to education,” she said, echoing demands that Citywide Youth Coalition presented at a rally last Friday. “I just think it would be more beneficial to have more different people you could call. Different social services, different healthcare professionals, rather than calling one group of people that don't have as much training and don’t know how to de-escalate.”

Both she and fellow student Ryan Piccerillo said they stand in support with protesters destroying property, although they were happy to be keeping it low-key with chalk on Saturday. Piccerillo, a 14-year-old who is studying dance at ECA, is a proud member of the school’s LGBTQ+ community. He noted that PRIDE didn’t begin as a glitter-soaked parade, but as a riot started by a Black trans woman.

“I think a lot of people forget that in the 1960s, it was Martin Luther King peacefully protesting, but also it was the Black Panthers and Malcolm X that brought it forward,” Greenshpun chimed in.

Bri Chance, an ECA and Wilbur Cross High School grad who is now a rising sophomore at the University of Connecticut, also advocated for a reallocation of police funds into public education. As a budding music educator, she said she’d like to see money go towards a more equitable school system, in which there are more programs designed for students who don’t have the same economic advantages as some of their wealthier, often white peers.

As she put the finishing touches on a game of hopscotch and blocky, purple BLM hashtag, she also called for more Black and Brown teachers in New Haven classrooms, and for schools to be equipped with a more robust history curriculum for the benefit of all of their students.

She speaks from experience as a graduate of those schools. Chance hails from Fair Haven and is Black and Puerto Rican, but had almost entirely white teachers during her time as a New Haven Public Schools student. During the part of the day she spent at Wilbur Cross, she saw plenty of Black and Latinx students in the student body, but very few in her advanced classes.

Studying music at ECA, she was one of only four Black students in her graduating class. She had no teachers of color, a factor that has motivated her to return and teach music in Fair Haven when she finishes her degree.

That divide reflects a wider disparity in the New Haven Public Schools system. As of last year, New Haven’s student body was 46 percent Latinx, 37 percent Black, and 13 percent white. Its teachers, meanwhile, were 9 percent Latinx, 15 percent Black, and 73 percent white. While the city’s student body may be largely Black and Brown, ECA is not—its magnet status draws in students, the majority of whom are white, from the city’s suburbs. Those suburbs, in turn, receive millions of state dollars for ostensibly integrating the schools.

It leads to a difference in how teachers teach, Chance said. She recalled a frequent struggle with one of her teachers at ECA, in which she was “labeled the crazy angry Black girl” after pointing out that the teacher had misgendered Galberth on a near-daily basis.

“They have no idea how to teach inner-city students,” she said. “When I went off, because I was sticking up for my friend, I was reprimanded. They said: ‘well, you know, you can’t break out like that in class.’ If any other white student did it, they’d be like ‘okay, okay honey.’ But for me, I’d have to be pulled aside.”

Maritsa Hristova, who runs social media at Koffee?, praised the project. "Humans need spaces to express grief, and always will. Creating and experiencing physical spaces communally is especially important now," she said. "This process gets us back to the mentality that physical spaces are a direct reflection of our humanity. How we use what we have is who we are."

But ECA was also where Chance saw the power of the arts to unite, she added. She became second chair flute, making friends with students she wouldn’t have gotten to know otherwise. She motioned to her friend, current ECA student Carly Hajducky, as she spoke. Hajducky is from Shelton. If it weren't for the school, Chance said, they would still exist in entirely different worlds.

“I had a wonderful time making music here,” she said. “I definitely think that art is a bonding force, no matter what you do. You don’t have to speak a certain language to access art. You can listen to any music, and it doesn’t have to be the Western canon.”

With the millions that currently go toward law enforcement, she proposed funding for programs to help students of color through AP and IB classes, give them more time with college counselors, and provide more complete history courses to every student. In the past few weeks, she has watched and listened as her white friends have come to her, asking for anti-racism resources for which there are now books, podcasts, Twitter feeds and entire Instagram accounts.

“It’s not wrong that they’re asking how to help, it’s wrong that they have to ask how to help,” she said . “It shouldn’t get to that point where we’re so divided that they don’t even know how to approach me anymore, and they talk to me like I’m an educator."

And yet, she’s also realized how much her own history courses left out. Last week, she learned about the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre for the first time, only after President Donald Trump announced he would hold a rally in the city on Juneteenth. None of her teachers had ever mentioned it.

“Our country has suppressed so much of our history, and that’s not fair to us, and it’s not fair to them either,” she said of her white peers. “They shouldn’t have to go on a scavenger hunt to find out about us. Nor should we.”

Those suggestions could come right on time: in 2019, the state legislature passed a law requiring that all Connecticut high schools be ready to offer a course in African-American and Latino history by July 1, 2021. During the same legislative session, New London Rep. Anthony Nolan pushed for and passed a bill that required the state to take action on minority teacher recruitment and retention.

| Amara Greenshpun: "I think a lot of people forget that in the 1960s, it was Martin Luther King peacefully protesting, but also it was the Black Panthers and Malcolm X that brought it forward." |

The New Haven Educators’ Collective has also issued demands, asking that the state expand its legislation to all K-12 education and include a more complete history of policing, as well as solutions that are geared towards divestment.

Galberth, an educator, spoken word artist and ECA grad who is now at the University of Connecticut, also used the event as a chance to talk about what a future without police—and with more intersectional movement building—might look like.

Born and raised in New London, Galberth described police brutality as forcing him to grow up much too quickly. He was 11 when Trayvon Martin was murdered, and images of a wide-eyed child in a hoodie filled his television screen. He was 13 when Michael Brown was brutally shot and killed by police, then left uncovered for six hours in the middle of a boiling city street in Ferguson, Missouri.

Later that year 12-year-old Tamir Rice was murdered by police for playing unaccompanied in a Cleveland park. Had he not been shot and killed, he would have graduated from high school this year.

“I didn’t even realize it was that long ago, because at the time I felt like a grown up,” he said. “You see another Black face die. I was so upset, and I was hit the same way when I was 11 that it does now.”

Now, he is also hopeful that there will not be an omission of Black queer lives and Black trans lives as protests gain traction, and spread across the country and the globe. As a Black trans man, it’s personal: he lives at two intersections that often provoke both verbal and physical violence.

With white and yellow chalk, he took to a section of red and brown bricks to remind viewers of names that are often not called out at protests: Tony McDade, Riah Milton, and Dominique Fells, all of whom were killed after George Floyd (Milton and Fells were murdered last week, within 24 hours of each other).

He added that while he’s excited to see more white and non-Black people of color showing up at protests, he hopes that they will do more to educate themselves on dismantling white supremacy. He recalled getting a text from a white friend he hadn’t heard from in months, asking what all the recent protests were about. He hit a breaking point.

“I just found it crazy,” he said. “I’m like: You can Google this! I just find it strange that so much of this information is readily available, but we’ve been so divided that they don’t know they need to go seek it out instead of like, asking me. I’m an entertainer-educator. That’s what I do. But it’s constantly exhausting to have to educate people in issues that honestly they should already be educated on.”

“It’s been the reality for mad long,” he added. “It’s good to see everybody coming together and realize this is an issue that we need to solve, but it sucks that it took this many Black lives lost for people to actually realize that we have to do something.”

Want to be an anti-racist? Here are some places to start.