Downtown | Film | Arts & Culture | New Haven Free Public Library

In a city of shrinking public resources, where are people supposed to look for help with drug addiction, mental health and housing insecurity? What are the resources to which they can turn? Can a library be their safe haven?

Should it be? What if the media isn’t on board with telling that side of the story?

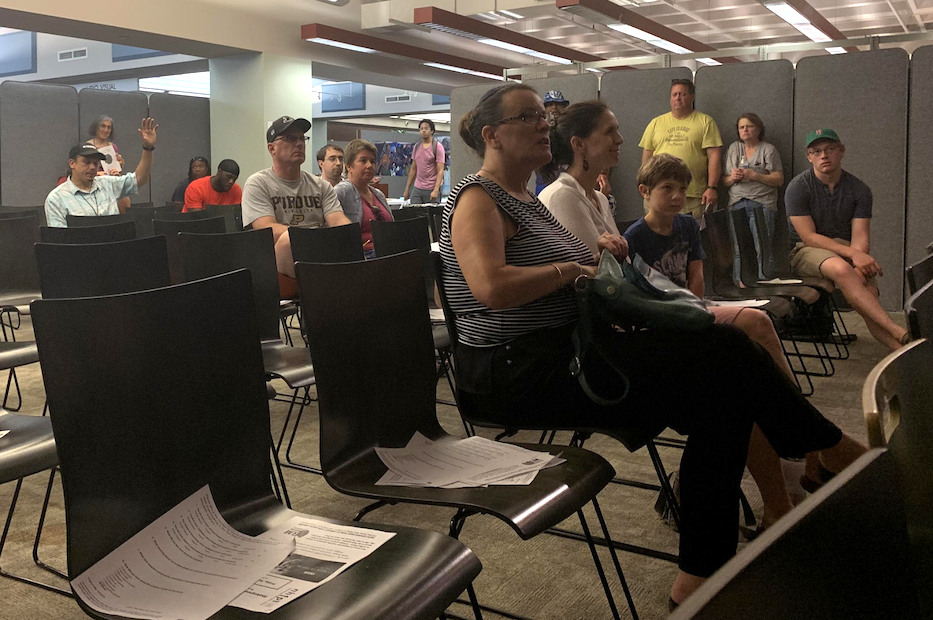

Those questions landed at the New Haven Free Public Library (NHFPL) Saturday afternoon, as community members joined recovery specialists, librarians, and housing advocates for a screening of The Public at the library’s downtown main branch. A discussion moderated by Silvia Moscariello, program director at Liberty Community Services, followed the film.

John Jessen, deputy director at the NHFPL, said that the screening was inspired in part by Ryan Dowd's The Librarian's Guide to Homelessness: An Empathy-Driven Approach to Solving Problems, Preventing Conflict, and Serving Everyone, which was published in 2017 and is a favorite among librarians and staff members at the library. When The Public was initially released, Dowd and The Public Director Emilio Estevez did a tour together to talk about the film, which gave library staff the idea of holding a public discussion.

"The book has been really great for us," he said. "The author sends a tip a week, and we send that out to staff. It keeps it out at the forefront of what we're doing."

Written and directed by Estevez (who also stars in the film), The Public follows a group of homeless people who refuse to leave the Cincinnati Public Library when emergency shelters are at capacity during an arctic blast. Based loosely on a story that appeared in the Los Angeles Times over a decade ago, it feels like it could be a real-life scenario in New Haven, where the library doubles as a warming center during the winter, but closes at 8 p.m.

In the film, a lack of housing security takes center stage. The group, led by Jackson (Michael Kenneth Williams) make a straightforward case: the library is a warm, public space where they are safe, and they risk suffering and even death if left to the elements. They have a sympathetic ear in Stuart Goodson (Estevez), a librarian who is friendly with the group, despite an ostensible hitch that becomes a sub-plot in the film.

But then the media runs with a clickbait-worthy story—that happens to also be devoid of facts—calling it a hostage situation. A hostage negotiator (Alec Baldwin) is called in. Recent history, in which a patron was evicted for body odor, is dredged up. It gets messy and cringe-worthy, in the way that fake news has a particular way of doing. The city’s mayor turns a cold shoulder to the library, a situation that is not too far from the struggling state of Ohio’s real-life library system, but feels far from New Haven’s support of its five branches.

| Jillie Ginty Photo. |

As the lights came up at the end of the film, several viewers noted similarities they see in New Haven, where the library has become a free and open resource, service hub, and warming and cooling center amidst increasing homelessness advocacy and need in the city. Currently, the library offers free computer classes, tax filing services, and English as a Second Language (ESL) classes. There are free art programs, readings, movies and book clubs for adults and kids.

It also hosts partnerships with the housing assistance nonprofit Liberty Community Services, NewAlliance Foundation and Long Wharf Theatre. And it has made itself a space for dialogue. Last summer, a group of protesters crashed an opening celebration for the library’s new Ives Squared innovations commons. Instead of turning them away, City Librarian Martha Brogan invited them in and began describing how the institution is working to address housing security in the city every day.

So, Moscariello asked, where does that leave New Haven vis-a-vis the film?

She pointed out that the film presents two political figures taking action, and that both seem misguided and uninformed. They might know the basic facts about Cincinnati, but they seem less informed when it comes to housing security and poverty. So is the first step an information campaign, to educate the public about both the library and those who use it?

That could help, suggested Downtown Evening Soup Kitchen (DESK) Executive Director Steve Werlin.

"The general public has a hard time wrapping their heads around mental health and substance abuse,” he said. “I work with the general public a lot, and there are a lot of volunteers, and I see it all the time. I see those sorts of stereotypes come out of people's mouth because they can't quite grasp it."

Other attendees (they declined to give their names) suggested that the functionality of a city’s government—or lack thereof—may also be to blame. Even when there are job opportunities, people who are housing insecure are less likely to get those jobs because they don’t have the adequate resources to prepare a job application or interview.

Some noted resources that exist, from locations for methadone maintenance to shelters that have become a source of contention in the city. One of those resources was Team Challenge, an addiction treatment center for men in New Haven.

Johnny Santos, a recovery peer specialist, said he came to a few conclusions by the end of the film. At the end of The Public, people still end up on the street. They—and viewers—must reckon with a chilling realization that even one night of rest is unattainable for the homeless characters. Once homeless himself, Santos said he recognized the challenge and pain that they faced.

He suggested that the film should be shown more widely throughout the city, to spread the message and spark discussion.

“This movie should be shown because I was homeless myself,” he said. “Just one day of rest not having to be out in this cold and I'll be alright."

Lucy Gellman contributed reporting.