Education & Youth | LEAP | Summer camp | Arts & Culture | COVID-19

| Emiya Pearse, who joined LEAP when she was nine years old. She is currently a junior counselor and will be a senior counselor next year. Lucy Gellman Photos. |

Emiya Pearse stood before an aerial map of Dixwell Avenue, landmarks tagged with red, green and yellow sequins. Thick black marker denoted James Hillhouse High School and Bowen Field. Another dot marked Southern Connecticut State University and the Beaver Pond Park nature preserve nearby.

Pearse pointed out Amistad High School, from which she graduated this year. She pulled up a webpage of black-and-white photos of the neighborhood and passed her phone around.

“What changed?” she asked. On the page, stately brick buildings rose on the street as Black men stood before them in suits. The question hung in the air for 10 seconds, maybe 15. Then three hands went up at once.

Pearse is a junior counselor at LEAP (Leadership, Education, Athletics in Partnership), a local nonprofit that offers several year-long and summer programs for New Haven kids. Wednesday morning, she was walking a group of preteen girls through “Future Mappers Of New Haven,” a curriculum she helped design with Yale undergrad Hamzah Jhaveri, Adeline Kim, Tyler Wakefield, and Dixwell Site Coordinator John Lee. The project asks campers to point out neighborhood locations that are meaningful to them, and reimagine what the Dixwell corridor could be.

“This is where our site is, and most of our kids are from this neighborhood,” Lee said Wednesday. “We want them to be able to reimagine its future.”

The format of the program allows LEAP to be flexible in the midst of a public health crisis. This year, the organization’s summer camps are a hybrid of online and in-person learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Depending on the week, the group meets either on Zoom or at King Robinson School, the latter of which comes with masks, outdoor activities in the Newhallville neighborhood, and near-constant sanitizing.

|

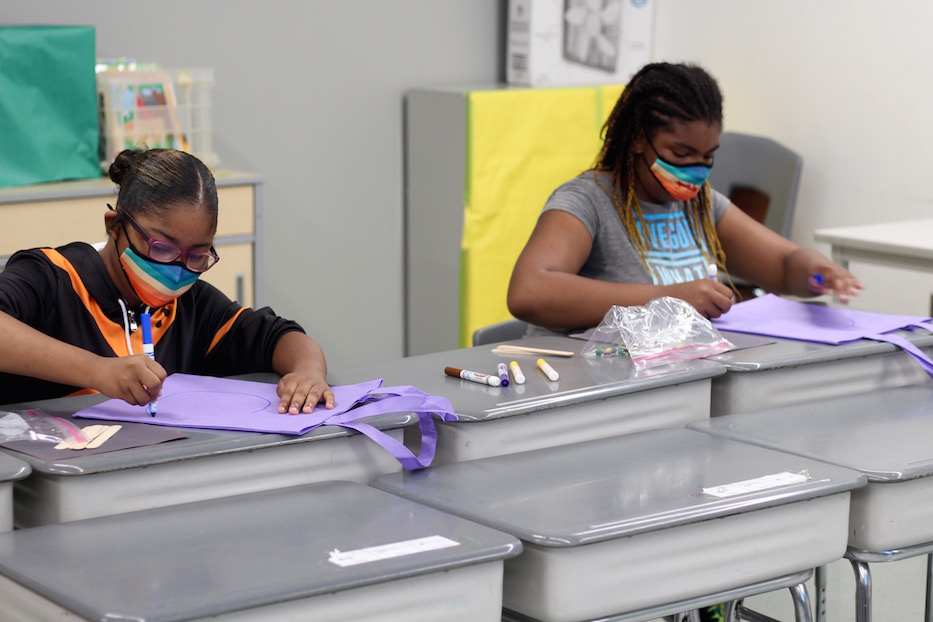

Makayla Hairston and Khloé Lawson-Stewart design bead mandalas with Lillian Aldarondo, Latinx community support specialist with the Girl Scouts of Connecticut.

|

Wednesday, LEAPers had just finished designing bead mandalas when Pearse hopped to the front of the classroom, where Lee had taped a map of Dixwell to the board. Signs of learning, suddenly interrupted, lingered from early March: a bathroom key hung from the dry erase board and a collection of boxes sat on a shelf above, still waiting for someone to come back for them. The rest of the room was empty and collecting heat, unaccustomed to visitors. A fan wheezed to life in the corner.

Pearse pointed to Amistad Academy, where the class had been planning to walk before they were delayed by an impromptu visit from the Girl Scouts of Connecticut. She traced Dixwell Avenue with a knowing finger, as if her hand was walking the length of it. Her left knuckle started at King Robinson and edged past Visels Pharmacy, First Calvary Baptist Church and Moe’s Market, where a mural now shows huge sparrows in flight. On the map, a trail of green sequins marked the way.

“This long, long street right here is the Dixwell area,” she said. “I’m gonna show you what Dixwell used to look like.”

Pearse passed around images of historic Dixwell, a neighborhood that thrived on the steady hum of the Winchester Repeating Arms Company. From the glowing screen of her cell phone, gas lamps stood regal on the street. An old grocery looked out with its sturdy brick facade. Students oohed and aahed even beneath their masks, eyes wide as they took each in.

“What’s different?” she asked. “What do you see that’s different?”

| Sage Edwards, Chloe Holloway and Taylin Pyles. |

A beat. Seven-year-old Sage Edwards, who attends Highville Charter School in Science Park, raised her hand. She pointed to an image of Black men in suits, standing regal by an old brick building. Her voice rose through her rainbow-colored mask, quiet and musical as her words poured out.

Taylin Pyles, a rising fourth grader at Highville Charter School, picked up the conversation. She gestured wildly as she spoke, her mask a nearly perfect match with a rainbow-colored slice of cake on her t-shirt.

“What about the Black Lives Matter movement?” she asked. “Also Stonewall? Had Stonewall happened yet? They had this person who came out as Black and trans [Marsha P. Johnson] … they didn’t like that back then. People were outcasted.”

Pearse nodded. Tracing the long arc of time just as she had travelled the avenue, she tied Dixwell’s long history to the Civil Rights era, scars of urban renewal, and lasting trauma and economic deprivation of structural racism, white supremacy the Transatlantic slave trade.

| Makayla Hairston and John Lee. |

When she got to the Columbian exchange, counselor Ramzia Issa hopped in. She gave an air high five to Makayla Hairston, who mentioned that a statue of Christopher Columbus had just come down in Wooster Square. Issa directed her attention back to the class.

“Don’t let them fool you,” Issa said. “He was a slave holder too.”

Pearse explained that that history—"this thing called colonization and capitalism”—has trickled into every aspect of life, including the way communities including Dixwell are built, divided, deprived of resources and destroyed. She returned to the original gentrifiers—members of the gentry, who were taking Indigenous land over a century before the Indian Removal Act brutalized Native communities.

Sage stopped the conversation. Her voice was so soft that the whole class leaned in to listen, still maintaining distance.

“Wait,” she said. “So you know how people buy houses? But they didn’t buy the houses. They took them. That doesn’t make sense.”

A round of supportive snaps echoed across the room. “It’s wrong for someone to take your culture,” Pearse said.

Then she switched gears: if students had $1 million to re-envision the Dixwell Corridor, what would they do?

“Based on the pictures, what would you put there?” she asked.

Taylin’s hand shot back up. “A children’s hospital!” she exclaimed. “And a park, with a statue of Harriet Tubman.”

She worked over the building’s contours in her mind, pausing as she spoke. As an aspiring doctor, she said she wants to see more healthcare in the area, especially for people who don’t currently have access to it. As she spoke, counselors applauded and snapped.

“I want to save lives,” she said. “Lots of people get sick. Especially in this time.”

“I like hands-on arts,” chimed in Khloé Lawson-Stewart. “Painting, building and pottery. My mom’s been wanting to build a school based on our Black culture. So maybe that.”

The ideas kept coming. Camper Chloe Holloway suggested a hospital with an animal shelter on the side. Sage said she could see following in her dad’s culinary footsteps, and building a restaurant. Counselor Alexus Lee, who just launched the business Beautyy In Art, said she would use it to support her business, her education, and her family.

Issa, who is studying healthcare management at Albertus Magnus, said she’d like to open a healthcare provider for people who don’t currently have access to free and affordable healthcare. She also noted the dearth of statues representing Black, Latinx, and Indigenous history in New Haven.

“Y’all are about to take over the world,” said Pearse.

| Chloe Holloway works on her bead mandala. |

Pearse, who is heading to Southern Connecticut State University in the fall, added that she would tear down Amistad Academy and build a center for mental healthcare in its place. It would be staffed with “the best of the best,” including the social worker she plans to become. She’s watched both family members and peers grapple with limited access to mental health services, including a family member that she lost to suicide.

After her first year at Southern, she hopes to transfer to Norfolk State University to study psychology, sociology and social work. She credited her years as both a student and a counselor at LEAP, which she’s attended since she was nine, as helping her build those academic goals.

“I’ve been in situations where LEAP has shown me how strong I can be,” she said. “The best form of health is mental health. There are a lot of things I can do, that are in my power, by just having a conversation.”

“Self-care is the best kind of care, just like self-love is the best love,” she later said, while passing an art assignment out to young LEAPers.

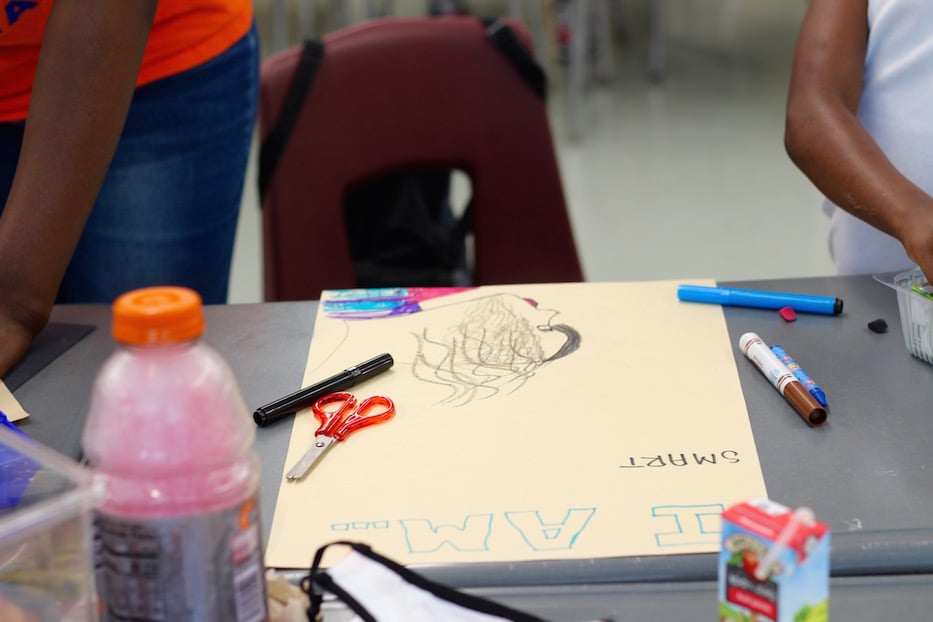

| The mapping discussion was followed by read aloud time and an art activity, in which students were encouraged to trace an outline of a woman and then describe their own character attributes. Pearse encouraged them to start with "beautiful and intelligent." |

The project comes as parts of the Dixwell Corridor, once brimming with Black-owned and operated businesses, arts opportunities, jazz clubs, and jobs, undergo plans for new economic development. At one end of the avenue, ConnCAT subsidiary ConnCORP has announced plans for a $200 million development where the Dixwell Plaza currently stands.

Across the street, the Q House is on track to be finished by early 2021, when it will be home to the new Stetson Branch of the New Haven Free Public Library. On the Farmington Canal nearby, a skate park and statue of Black engineer William Lanson will both be going in by early fall. Community advocates have been vocal about the need for affordable housing as the neighborhood changes.

It ties in to campers’ plans for the remainder of the week, added Lee. On Thursday, campers were planning to walk from King Robinson to the Newhallville Learning Corridor on the nearby Farmington Canal Heritage Trail.

Mapping Home

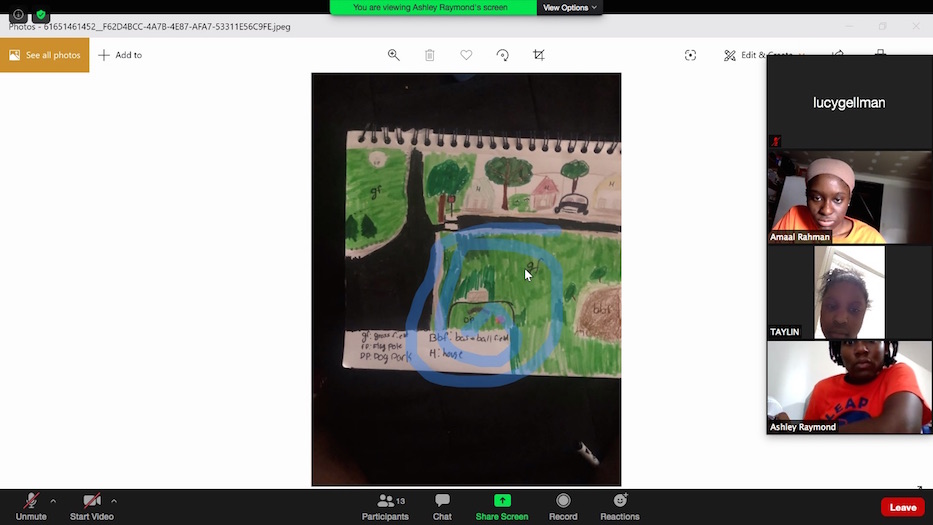

| Zoom Screenshots. |

Wednesday’s lesson built on mapping that LEAPers have done for over two weeks, from the Zoom screen to their meetings beneath tents outside King Robinson. Last week, Pearse, counselor Ashley Raymond, and counselor Amaal Rahman walked students through a virtual exercise that asked them to map their homes, complete with a key, compass rose, and a legend. The group is using “Never Eat Soggy Waffles” as its trusty memory trick.

On a recent Wednesday over Zoom, some students were still finishing their personal geographies. Rahman showed LEAPers a map she had drawn from Ghana to New York, where she was born in Yonkeres. The map hopped to West Haven, where her family moved in 2003. It showed Georgia, where she has extended family, and travels she has had in Canada and North Carolina.

“It’s full of culture here,” she said. She described a community garden down the street, and the noisy neighbors that she has come to love.

Camper Janaya Crocker, a student at Booker T. Washington Academy, lifted a map up to the screen of places she wants to visit, including Australia and Greenland. She recalled traveling “down South” to the Carolinas to visit her grandparents.

Taylin described her own house and neighborhood as Raymond screen shared a hand-drawn map. In bright green and blue, there was the Carlisle Street corner store where she gets sweet, cold slushies topped with coconut flakes (asked to propose a change, she suggested that the slushies should be 5 cents instead of 50). She suggested adding a cat park element to Trowbridge Square Park nearby.

“In all seriousness, I would like to change the community,” she said.