Community Management Teams | Public art | Arts & Culture | Wooster Square | History

Marc-Anthony Massaro Rendering.

Neighbors showed up to express their concerns that a monument did not adequately reflect their community. In response, the artist has scaled back the design, proposed removing a fence, and doubled down on his commitment to telling an Italian immigrant story in one of the city’s most beloved public greenspaces.

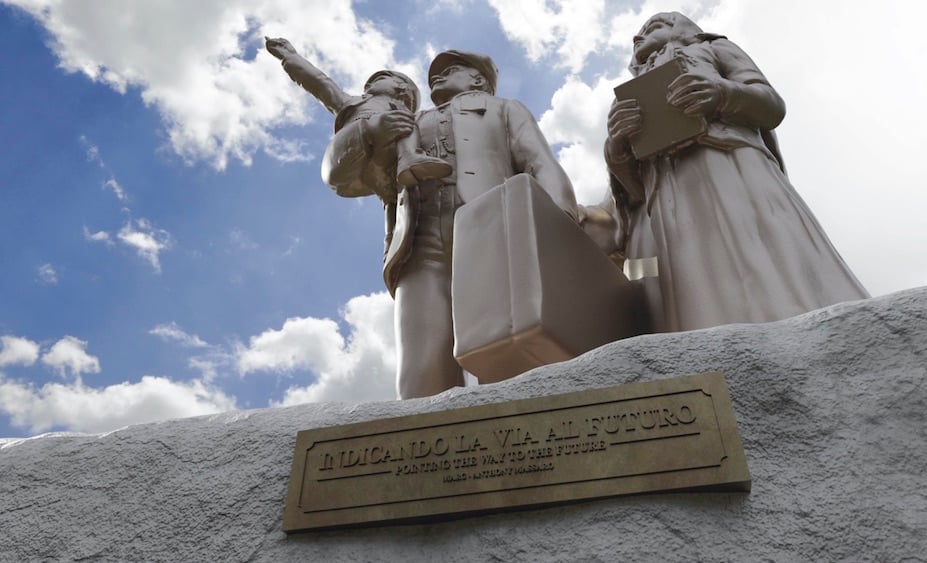

That is the latest chapter for the Wooster Square Monument Committee, which spent this month reworking its proposal for a public statue in advance of a Feb. 9 meeting with the Historic District Commission. Over 18 months after the commission began its search and five months after it selected Marc-Anthony Massaro’s Indicando la via al futuro (Pointing the Way to the Future), it is still working through the finer points of what that monument will look like.

“The sculpture that Marc Massaro designed is not subject to change,” said Bill Iovanne, who has co-chaired the committee since its first meetings in late summer 2020, at a meeting last Wednesday. “This is what people voted on and this is what the design is. This is the preferred selection of the committee … what you are seeing is a direct result of our feedback from the community.”

The work will replace a monument to Christopher Columbus that came down in June 2020. The statue itself—an Italian immigrant family of four, looking toward the horizon line as they arrive in the United States—has been the heart of the design since last summer, when it was selected from six finalists in late July. Originally, Massaro proposed a statue that would lower and integrate the original stone pedestal and add a surrounding stone plaza, with four didactic plaques, six curved stone benches and potted conifers.

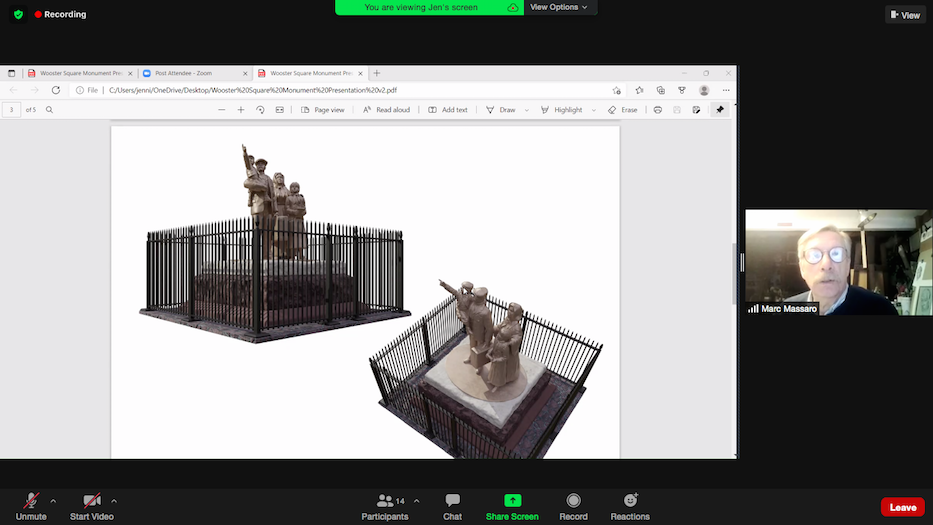

Marc-Anthony Massaro's rendering from the December meeting of the Historic District Commission.

Then last month, the design became part of contentious meetings of the Historic District Commission and Downtown Wooster Square Community Management Team. At both (watch them here and here), neighbors expressed concern that the plaza was too large for the park, paving over valuable greenspace. Some saw the plan as ill-suited to the area, from its materials to its landscaped elements.

Several also pointed to the flat-footedness of Massaro’s nostalgia-drenched design, which depicts a white, Christian, heterosexual family in a neighborhood that is increasingly queer and nonwhite.

At the December management team meeting, Anika Singh Lemar, who lives on Chapel Street with her husband and children, pointed to the fact that almost everything in the neighborhood pays tribute to a 50-year chunk of Italian history, but leaves out its Irish immigrant past and rich, very much living history of Black and Latino residents. That includes nineteenth-century Black engineer William Lanson, who built the city’s Long Wharf and bought and developed property just east of Wooster Square.

“The architecture’s eclectic, you’ve got fancy town homes two blocks from public housing, you’ve got a diversity of housing typologies, diverse population, and we have hundreds and hundreds of new units going up,” Lemar said. “This is a neighborhood that is not only diverse and eclectic, but one that welcomes change and evolution. And when I walk around the neighborhood, the kind of public art and monuments don’t acknowledge that at all.”

Marc-Anthony Massaro Rendering.

“A monument that’s focused on one particular type of immigrant or one particular type of family really doesn’t tell the whole story of the community,” added Lana Melonakos-Harrison in the same meeting. “I definitely hear you [Bill] when you say that the mayor charged you with a specific task here, and that’s a challenging mandate to work with, but I think that it’s totally appropriate for you all working on this as well in collaboration with the community to push back on that.”

In response, Iovanne said that the committee planned to integrate community input and submit a new proposal to the Historic District Commission in February. It also met with members of the Historic Wooster Square Association and sent out a survey for neighbors, presenting four variations on the same, scaled-back concept. Massaro began shrinking the design dramatically, from a landscaped plaza to a single explanatory plaque, sculpture on the stone pedestal, and stone veneer base with matching planters. The committee discussed moving explanatory plaques to nearby Russo Park, the strip of grass across the street.

For a brief moment, it also looked as though members might look inward and reassess their work. Then meetings resumed in mid January.

To Fence Or Not To Fence

This month, members have spent a cumulative three and a half hours debating whether to lower the tall wrought iron fence around the pedestal, orient the sculpture towards or away from Chapel Street, and bring the work closer to eye level.

As committee members reviewed an updated design from Massaro earlier this month, the fence took center stage. Currently, it stands around the empty pedestal, which must remain in place for preservation purposes (while the Columbus statue was originally cast in Massachusetts over a century ago, the pedestal was built by local stonemasons). The committee is proposing lowering the pedestal, for which it will need approval from the Historic District Commission.

In December, Iovanne proposed removing the six-foot fence in the committee’s presentation to the Historic District Commission. One month and several meetings later, he maintains that point of view, he said. “My concern is the height, and that it doesn’t look like these four people are in a jail cell,” he said in a Zoom meeting earlier this month.

“My personal opinion?” Massaro chimed in. “The fence is terrible for it. It makes them look like they’re in a prison.”

“Fencing off the statue is symbolically opposite to the theme of welcoming immigrants,” wrote John Lindner in the chat.

Committee member Elsie Chapman suggested lowering the statue to ground level, a suggestion that Massaro has since integrated into a four-foot platform surrounded by flowers and plants at the base. Both she and Massaro’s studio assistant added that there could be a risk factor: kids climbing on it. (No one pointed to Los Fidel, a local organizer who climbed the fence and then stood atop the pedestal himself, right fist raised in the air, one day after the monument came down).

“Four feet does not deter kids from climbing, and something will have to be done to make sure the city doesn’t get sued,” Chapman said. “Without some kind of barrier, kids will climb on it, because that’s what they do.”

“Parks are for living,” Iovanne countered. “That’s what they're here for.” He noted that kids climb the cherry blossom trees every year. Sometimes their parents do too. They know the risk and do it anyway.

Frank Carrano, a longtime champion of the neighborhood who supported Columbus coming down, had a more candid take: “I don’t think that’s our job.”

East Rock/Cedar Hill Alder Anna Festa pointed to the monument of William Lanson on the Farmington Canal Heritage Trail. Sculptor Dana King, who installed the work in September 2020, has spoken about how she wants young people to approach it, to touch Lanson’s clothes and hair, and see themselves reflected in his centuries-old history. There’s an opportunity for intimacy there, she noted.

“I think that we are far too … overthinking kids climbing on it, kids falling off it,” Massaro said. He returned last week with renderings of a fence-less monument. “If kids are gonna climb on it, they’re gonna climb on it. And I don't know how many monuments in New Haven people have climbed on, but they’re gonna do it!”

Members also briefly debated turning the family toward Chapel Street, where Columbus fixed his vacuous land-grabbing gaze for 128 years. Carrano suggested that this too could look out toward the street. Ultimately, Massaro’s renderings kept the family facing in, toward the park.

“I don’t think I agree with Frank,” Charlie Murphy said. He pointed to Water Street, which was once open water. “It would have been looking out to the water, which made a great deal of sense. Now it faces the park. The people who are in the park, and use the park.”

The Historic District Commission meets virtually Feb. 9. View their meeting schedule here.