Public art | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | Wooster Square | Elicker Administration

A sketch from brothers Joshua and Jonathan Kuhr is one of six finalists for a new monument in Wooster Square. Photos from Zoom.

Two brothers imagine a plaza around the pedestal, where a fig tree blooms beside the story of Italian-American immigration to New Haven. An artist-architect team sees four figures locking arms and gazing out over the park—but wants to ask the community for more input before anything is set in stone. A third sculptor envisions an immigrant family standing there, on the lip of their own story of coming to America.

Wednesday and Thursday evenings, six finalists presented those ideas to the Wooster Square Monument Committee, bringing the city one step closer to replacing the monument of Christopher Columbus that came down in June 2020. It follows over a year of discussion and spirited debate from the group, two dozen members of which were appointed by Mayor Justin Elicker less than a week after the statue came down. The meeting took place over Zoom.

Over the past year, members of the committee have met to discuss what they hope to see in the park, collect ideas from the community, sketch out a vision and open the process to artists (read more about previous committee meetings here, here, and here). Of over 100 initial ideas and dozens of proposals, members of a subcommittee have selected six finalists.

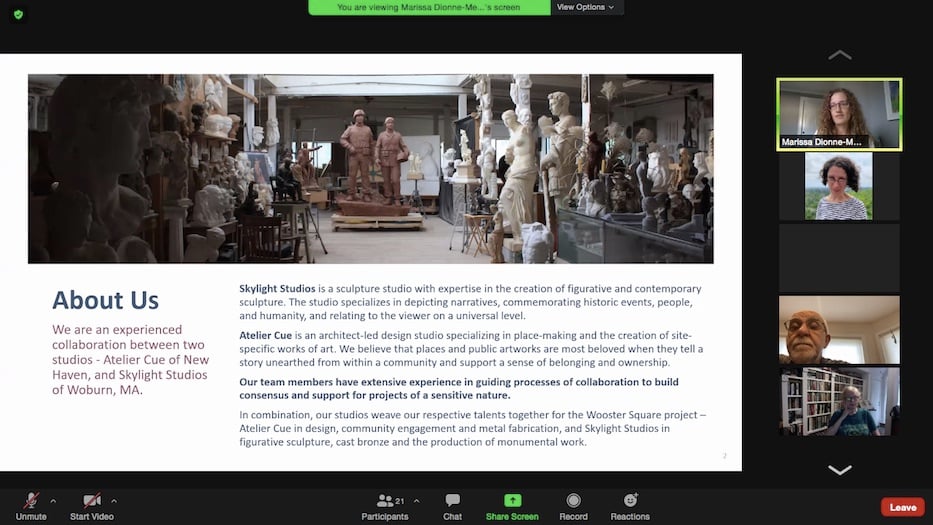

One possible idea from Atelier Cue and Skylight Studios.

They include a collaboration between New Haven-based Atelier Cue and Woburn, Mass.-based Skylight Studios; Bethel sculptor David Gesualdi; New Haven and Branford sculptor Marc-Anthony Massaro; Cheshire-based artist Tony Falcone; New Haven and Massachusetts-based brothers Joshua and Jonathan Kuhr; and former committee member Richard Ramadei.

All proposals incorporate the current pedestal, some kind of landscaped element, and a series of narrative panels tracing the Italian immigrant experience in New Haven (read the initial RFQ that went out to artists here). Per its initial charge from the mayor to “honor the contributions of Italian American heritage in New Haven,” the committee has not discussed a call to recognize Black and Indigenous people in the space, which sits on seized Quinnipiac territory and was developed in part by the Black engineer William Lanson.

The committee has proposed working with a $250,000 budget, for which members are already applying for grants. Committee co-chairs Bill Iovanne Jr. and Laura Luzzi have stressed that none of the funding comes from the city; the group has already submitted an inquiry to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation’s Monuments Project. Members will next meet to discuss the proposals and narrow the list down to three in a public meeting on July 28.

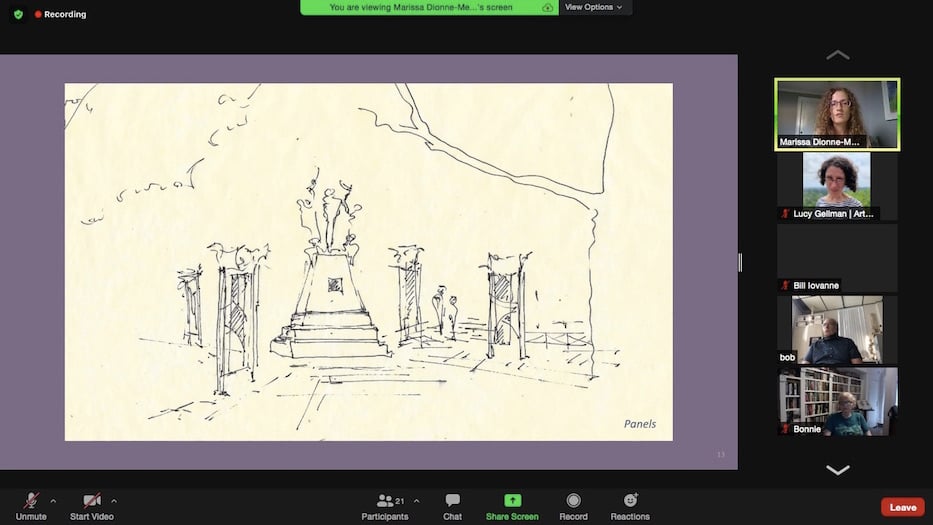

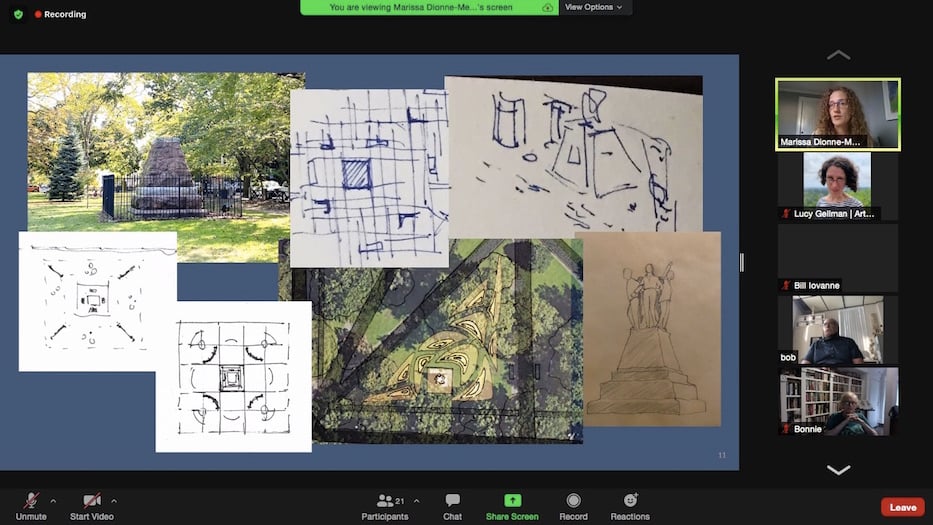

Wednesday and again on Thursday, finalists presented concepts that spanned interpretive, large-scale public art to intricate, figural sculpture. Marissa Mead and Ioana Barac, founders of Atelier Cue, kicked off the evening by sketching out a four-sided monument, surrounded by narrative panels printed with text and photographs and an “element of procession” leading to the monument site. The panels would be printed on aluminum; the studios are still playing with placement of those panels.

“We would want the piece to first embrace the viewer with the narrative panels, and then sort of escalate the experience in a crescendo going up all the way to the top of the sculpture,” Mead said.

The two would be working with sculptor Robert Shure and Kayla Fletcher of Skylight Studios, which is based in Massachusetts. Pulling up their presentation, Mead said that they envision multiple designs for the space, including a four-sided monument with figures locking arm and looking out onto the square. They see the monument as a piece with multiple figures, representing the multigenerational story of immigration. Mead added that it could just as easily be an allegorical piece, such as the studio’s Rising Unity sculpture at the State Capitol building in Hartford.

In that same corner of the park, they and Skylight Studios have also considered a landscaped design that would move into and out from the space where the pedestal still stands, surrounded by a high fence.

Mead said that such a design could mark the site as a point of transition. Both Atelier Cue and Skylight Studios are rooted in site specificity, meaning that they are already thinking about the park and the neighborhood’s relationship to a potential work of art. Shure, who grew up in an Italian household, said that he feels attached to the commission. As a sculptor, he works largely in bronze and granite.

For Mead and Barac, who run their studio out of Erector Square in Fair Haven, the design is still in flux because the New Haven community hasn’t yet had the chance to weigh in. In New Haven, Cue has become known for its people-centered approach, including multiple meetings for neighborhood input and community involvement in the production process. Earlier this year, the studio worked with Town Green Special Services District to install the first phase of “Intersection To Connection,” a public art project meant to knit together Downtown and Wooster Square.

“We know there are many impassioned viewpoints about what this piece should be, and people have opinions about a lot of the specifics,” Mead said. “An experienced, well-led engagement process could really help to center our community around this project.”

“The monument should really inspire our collective hope for the future,” she added. “While immigration is the story of the first generation of travelers, it’s also a story of their children, and of their grandchildren. Each generation represents this resurgence in this hope for a joyful future … we would want this piece to invite the question: ‘Who will the next great-grandchildren of Wooster Square become, and what will they achieve together?’”

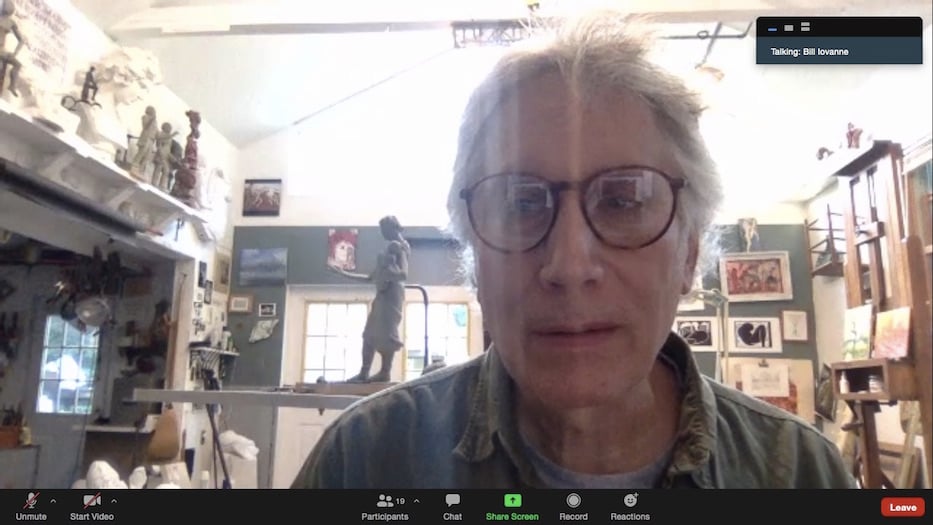

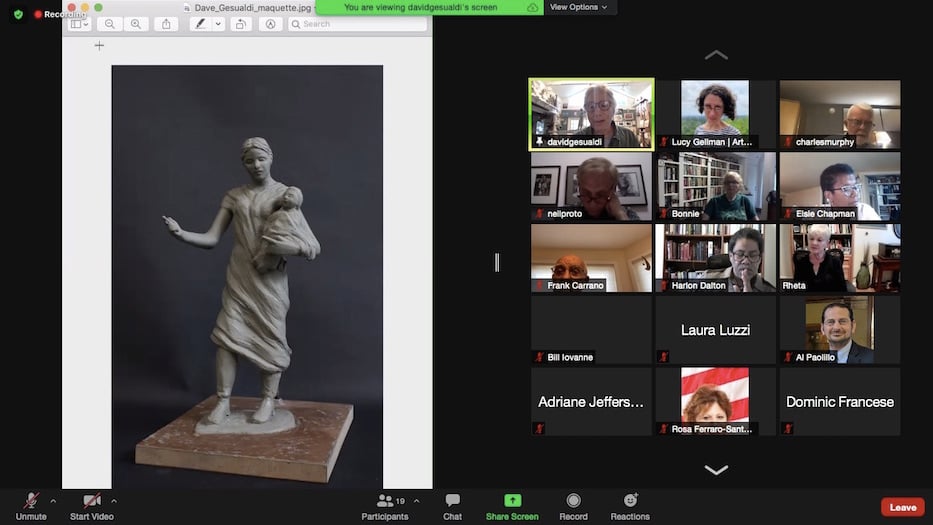

Gesualdi, who is based in Bethel, tuned in from his studio. As he came into focus, sculptures reached out behind him on both sides of the screen. Noting that his design was still fairly preliminary, he pulled up a small clay sketch of a mother cradling a baby in one arm, and pointing out in front of her with the other.

Her dress flapped and pulled against her legs. The baby opened its mouth just a tiny bit. He said he saw the woman as an Italian immigrant mother still on a ship, catching her first glimpse of her new life in the United States.

“She’s gesturing down to her child, here it is, this is freedom,” he said. “We’ve made it. Perhaps the father or whoever is behind her, or doesn’t need to be present. Perhaps he’s on shore, waiting for the family. But the child represents the future. That’s the symbolism there.”

Gesualdi added that he sees the message as one that echoes through today, in a city that continues to welcome immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. If selected, he would sculpt another, larger rendering of the sculpture based on a live model in period dress, and ultimately have the work cast in bronze. He said he had not considered the narrative panels that are part of the process.

Like Mead and Barac, he said he also would like to get more input from the New Haven community. He said that his approach is normally to “reach out first … and then begin to distill it into a piece of sculpture that the community really feels they have ownership in.” He pointed to the Bethel War Memorial, a collaboration with veterans that he sculpted in 2001.

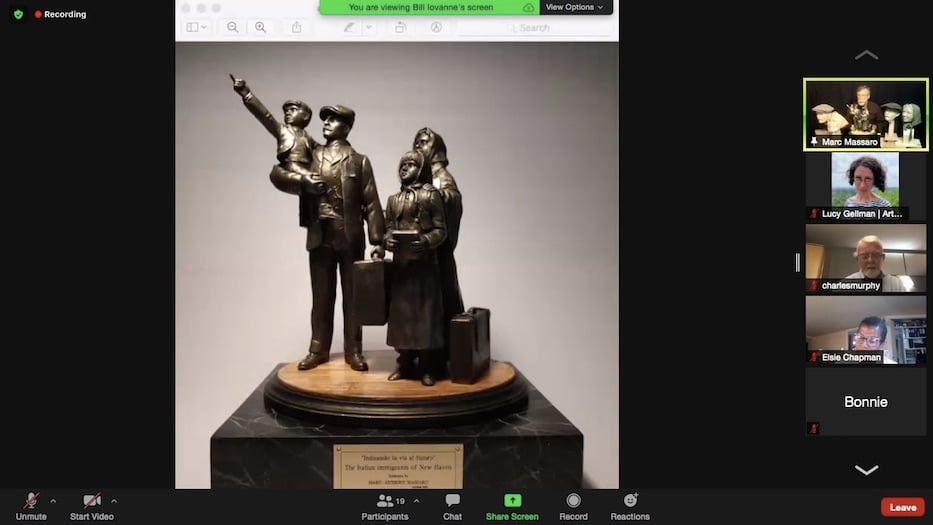

Massaro, who grew up in New Haven and is now based in Branford, proposed a larger version of his 2020 sculpture Indicando la via al futuro (Pointing the Way to the Future). In the weeks after the statue of Columbus came down last summer, Massaro began working on a miniature of the sculpture as a personal passion project. He said that he was able to complete it so quickly because it “had been percolating” in his head for almost 15 years.

He said he was also inspired by his students, who started asking him “Who is the famous Italian you’re going to sculpt now?” Instead of turning the clock back to Columbus’ voyage, he chose a more recent history of nineteenth-century immigration from Italy. He wanted to tell the story not of a person, but of a family with bright hopes for the future.

“All famous people, past and present, regardless of your gender or national origin, have baggage,” he said. “And there are things that are not necessarily flattering to their public image. Picking another famous Italian to replace Columbus would be putting us all right back on square one.”

Instead, Massaro came up with a sculpture of a family of four, which would be rendered in bronze with period outfits. Based on his grandfather, he has sculpted a father who “is the breadwinner,” as well as a mother, son and daughter. The son, carried in his father’s arms, is pointing to something in the distance. The daughter holds a heavy book, which is meant to represent “the opportunity of education.”

Wednesday, he appeared surrounded by life-sized heads, who wore caps that his father and grandfather once owned. He brought one up to the camera in what felt like a crackly, low-lit interlude from Madame Tussauds.

“This is a celebration of the human spirit,” he said. “It needs very much what it is to be human, for people to connect with it immediately. It’s an image of joy, the anticipation, and excitement of a new life in a different country.”

The sculpture is also personal to him: Massaro was born and raised in New Haven’s Italian-American community. He is the great-grandson of Frank Consiglio, a fisherman from Amalfi who moved to Wooster Square in 1918. His mom’s cousin was Salvatore Consiglio, who went on to found Sally’s Pizza in 1938. Massaro grew up going to family gatherings at Sally’s and the St. Andrew’s Society, where “I felt like I was in another country”. In 1971, a scholarship from the family of Wooster Square artist Gabriel Luchetti sent him to college.

“I can’t see a more fitting way for me to honor and respect my grandparents,” he said.

He showed the committee a rendering of the bronze atop the pedestal, surrounded by etched narrative plates on a 45-degree diagonal to leave the space open. He added that he would be sure not to allow the plates to obstruct the view of the monument. He said that he estimates an 18-month timeline to sculpt the work in life size and bring it to a foundry.

He said that he believes New Haveners can look at the piece, and see themselves reflected. Iovanne, who grew up in Wooster Square and now runs Iovanne Funeral home, said he was personally moved by the artist’s attention to detail, including a cross around the daughter’s neck and a wedding ring on the mother’s finger.

Elsie Chapman, who has lived in Wooster Square for nearly two decades, pushed back gently. She noted the diversity of the neighborhood, which has welcomed many Asian-American, Black, LGBTQ+ and Latinx residents in the past decade. Earlier this year, Lyon Street put itself in the running for the gayest street in New Haven.

“All of whom might not identify with some of the themes that you have indicated,” she said. “Didn’t really speak to some of the emerging races and diverse cultures that we’re seeing on the square.”

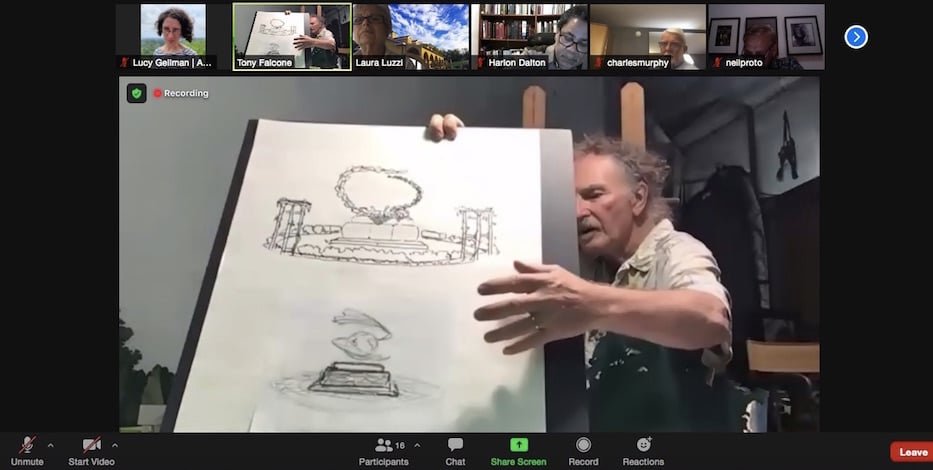

Artist Tony Falcone, who lives in Cheshire, came to the committee from behind a neat maquette with tiny green trees, a thick, shimmering wreath, people made of pipe cleaners and two doll-sized pergolas. Behind him, a large pencil sketch covered the back wall. He has been working closely with Judy Andrews, who is his partner in work as well as in life.

In his vision, the monument is flanked on both sides by benches and pergolas, which double as transitional entryways and are a nod to Italian gardens with climbing grapevines. Through the pergolas, Falcone imagines a stone walkway surrounded with landscaped shrubs and perennial flowers. He is already in discussions with the Branford Quarry about stones for the walkway.

Mounted on a lowered version of the existing pedestal, the piece de resistance is a swooping bronze or metal wreath that starts at eye level, standing tall over a sculpted picnic of bread, cheeses, and a full pitcher.

“I would hope that that would get that message across, with the symbols for the bounty,” he said. “Not only working hard, planting a garden, but also planting your seeds in work and in life.”

The wreath itself is meant to speak to multiple facets of the Italian-American immigrant experience, said Falcone. It includes two symbols of Italy, the oak cluster and olive branch cluster. Falcone has done one classical rendering that he imagines in bronze, and a more contemporary, abstract rendering that he said could be aluminum or another type of metal.

“The fact that it’s sort of wreath-shaped gives you such good movement, and from side views, or front views, or back views, it seems open,” he said. “It doesn’t seem static to me. It has a wonderful, graceful space to it and it activates the space really well, which is what I believe public art should do.”

“It becomes more or less a frame,” Andrews added. The two have imagined surrounding the sculpture with newly landscaped elements including cedar, cypress and poplar trees, all conifers that would add bursts of green to the park even in the winter.

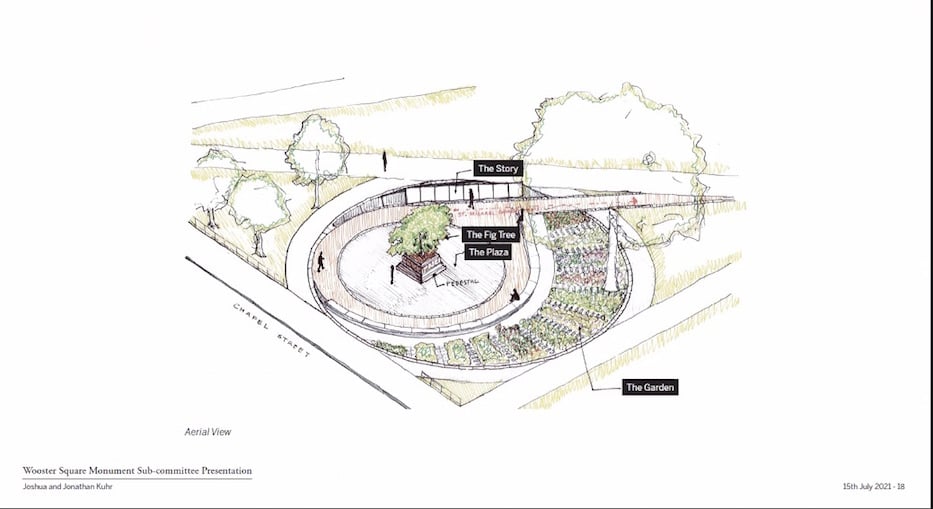

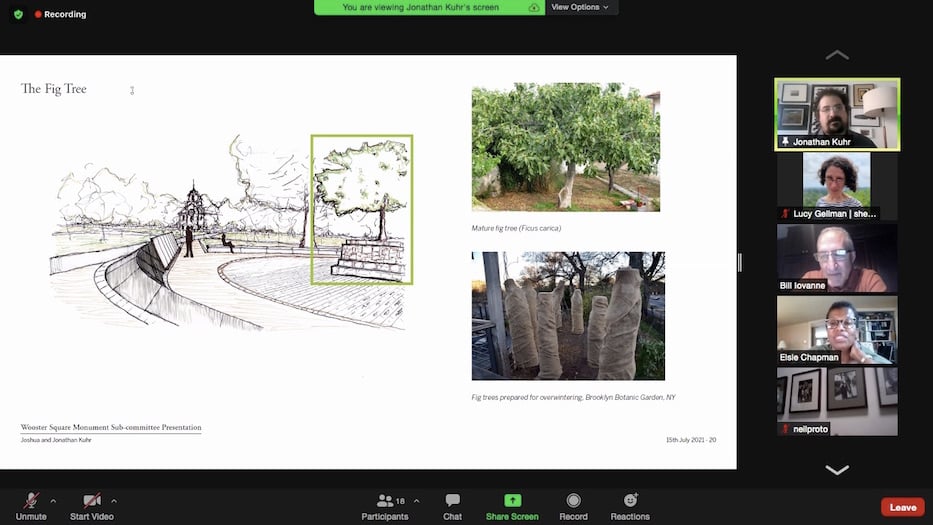

Thursday evening began with designer and brothers Joshua and Jonathan Kuhr, who are based in New Haven and Malden, Mass. respectively. Nine years ago, Joshua moved to New Haven to work for Cesar Pelli, the heralded Argentine architect who died in 2019. The two brothers have also done research into repairing the wounds of development and urban renewal in New Haven, particularly in its West River neighborhood.

“Our ethos as designers is really about honoring place,” said Jonathan. “Understanding the history and culture of where we’re working, and infusing that understanding into designs that engage the community both directly as spaces for understanding, and indirectly as sites that spark conversations about the past, present and future of a place.”

With that process in mind, the brothers embarked on deep research into the history and legacy of Italian immigration in the U.S. and New Haven. Jonathan said that they zeroed in on gathering, with particular interest in Italian gardens and the plaza or public square that is so common in Italian architecture.

The current proposal makes the monument “not an island, but rather a node or a gathering place connected to the community,” Joshua said. The two brothers imagine creating a circle, at the center of which the pedestal stands as a repurposed planter with a live, blooming fig tree where Columbus’s heavy bronze feet once rested.

The fig tree is a nod to the fruit-bearing plants, sometimes just twigs or clippings, that families brought with them from Italy. In the colder climate of the Northeast, immigrants had to learn how to keep the trees alive against the harsh winter.

“And yet with hard work they grew and they thrived, and they bore fruit year after year,” Jonathan said. “A plant born in Italy could thrive in the United States. And that with hard work, really anything was possible.”

As he described it, Joshua painted a picture of the pedestal-turned-planter on an axis with St. Michael’s Church, the narrative panels all presented to one side. Beyond, the two brothers envision bench seating and a community garden. They see paying homage to the piazza form, while using materials from New England.

Jonathan suggested that the community garden could become a space for communal activities—he suggested Wooster Square tomato canning—and lend itself to oral histories from families in the neighborhood. He pitched the garden as a space that neighborhood youth could maintain and cultivate.

At the end of the brothers’ presentation, Iovanne seemed visibly moved.

“It’s one thing to read a presentation like that, it’s another to hear it from your perspective and your personal tie to it,” he said. “Which brings good feelings to me.”

Ramadei said he wants to see Columbus go back up and proposed painting the statue in polychrome paint. Iovanne ended the meeting by gently reminding him that the committee was assembled specifically for a new monument.

The next meeting of the Wooster Square Monument Committee will be on Wednesday July 28 at 6 p.m. Access it on Zoom here.