Culture & Community | Opinion | Arts & Culture | Community Heroes | Arts & Anti-racism

Some of the artists who made waves this year. Top row: Martha Lewis, Semilla Collective, Eric March. Middlr Row: Vanesa Suarez, Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez, Alasdair Neale and the New Haven Symphony Orchestra. Bottom: Black Lives Matter New Haven's Ala Ochumare-Harris, MiAsia Harris, and Sun Queen, Roya Mohammadi, Destiny White, Erin Michaud and Jeremy Thanes. Lucy Gellman Photos.

In April, it came as the request that board members at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art step down before the end of the year. In June, it was in the call to investigate the death of a fallen sister, taken long before her time. In July, one could see and hear it in a music festival by and for young independent artists, especially artists of color. By October, it unfolded across Erector Square, as artists organized a weekend of open studios when they realized that no one was going to do it for them.

And this fall, it echoed through displays of resistance through joy, musical calls to treat each other as human, and negotiations for fair compensation among musicians and arts workers at the New Haven Symphony Orchestra.

In 2023, our artists of the year were those who spoke out, who pushed back, who challenged institutions and championed mutual aid and collective care over the perceived needs (and often, lip service) of entrenched nonprofits. For 12 months, they celebrated artmaking, broke away from capitalism, called out longstanding patterns of harm, and centered social justice in their work, from new grassroots collectives to LGBTQ+ advocates and students who took school policy into their own hands.

"For the many years that I worked in nonprofits, I often found that I had to push past my capacity to be reaching whatever imaginary expectations, whatever imaginary goals, existed that were unrealistic," said Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez, who founded Fair-Side earlier this year, in an interview with the Arts Paper last summer. "And in this work, it's been really healing to go at this with our capacities and our bodies in mind."

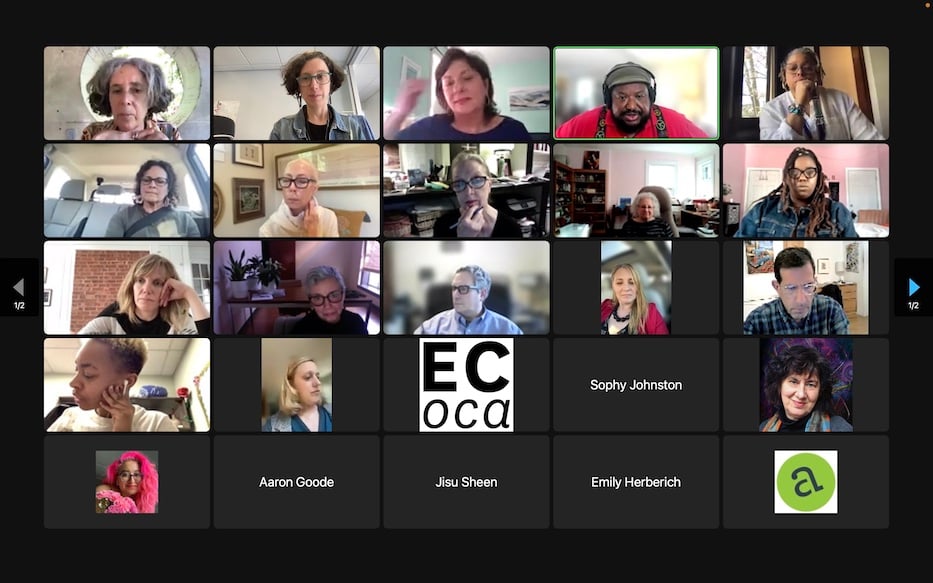

A meeting of Ely Center board members and New Haven community members in April. Screenshot via Zoom.

In 12 months, that took many forms, from artists who demanded institutional and systemic change to those who suggested that they didn't need nonprofits after all. In April—just weeks after the feather-ruffling resignations of directors at Artspace New Haven and Creative Arts Workshop—multimedia artist and arts worker Max Schmidt spoke out about alleged harassment he had endured and witnessed at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art, telling his story after board members alluded to harm, but gave so little context that it left dozens of community members scratching their heads.

It set off a series of meetings in which board members promised an employee handbook, stronger guidelines and board turnover at the nonprofit (the third has not yet happened; it's unclear whether an employee handbook ever emerged from the discussions). Meanwhile, it also provoked a reckoning among some of the city's artists and curators, who pulled out of exhibitions at the institution and advocated for Schmidt as they listened to him speak about treatment of artists in the space.

One of those artists was Gonzalez Hernandez, for whom it ultimately became a year of building community, launching new forms of practice, and issuing a number of institutional call-ins. In early May, she joined neighborhood organizers for a triumphant return of Fair Haven Day, held outside Fair Haven School and the Grand Avenue branch of the New Haven Free Public Library. As festivities unfolded outside, she welcomed patrons to the first exhibition from Fair-Side, a community of Fair Haven artists and makers that has continued to flourish in the months since.

Ruby Gonzalez Hernandez. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

“I want to hold space and be in community with artists to simply be artists,” she said at the time. “To make art, and not under the gaze of an arts institution. I started Fair-Side with no need for people to buy in: I wanted to ensure that artists from all different areas, from all different art forms, felt welcome here.”

Even as she cared for artists around her, she didn't stop organizing. In August, Gonzalez Hernandez organized the inaugural Artists State of the Union, an hours-long meeting of New Haven artists and creatives at Bregamos Community Theater. With singer, songwriter, poet and arts worker Briana Williams, she facilitated hours of discussion, about everything from nonprofits that have earned the community's trust—or not—to whether artists feel included in New Haven's Cultural Equity Plan.

For her, the idea of harm far exceeded (and to this day exceeds) a nonprofit's potential harassment, gaslighting, or abuse of an employee, she said—it's also present in the low pay, long hours, and emotional labor often expected of nonprofit workers in the cultural sector.

"I think about the price that employees paid and are continuing to pay," she said of her work at one such city institution at the time. "No one's health and safety is worth sacrificing for the work."

"I want you to know that another future for artists is possible," she later added. "A creative future is a safe one."

Vanesa Suarez and Camila Güiza-Chavez in June. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Elsewhere in the city, that force of artist-activists speaking truth to power had also taken root. After the sudden disappearance and death of Roya Mohammadi in March, photographer and activist Vanesa Suarez, members of Justice 4 Roya, and the evolving collective Vivan Las Autónomas continued pressing the West Haven Police Department on answers in her case, rallying around the cause in West Haven in June, and then again in Orange and West Haven in November.

That's not new territory for Suarez: her photography from Chiapas, Mexico has also addressed femicide and self-governing, matriarchal systems of power meant to protect women when laws and governing bodies do not. Since mid-2020, she has been an outspoken advocate for victims of femicide and survivors of sexual harm in Connecticut, urgently reminding people to remember and speak their names as much of the legal system—and the state—moves on.

Throughout an extremely heavy year, Suarez has also highlighted artmaking as both a form of advocacy and a way to manage and navigate the grief that has hung over every gathering, phone call, and call for police accountability that she and others have issued. Before a march for Mohammadi in November, she organized several artmaking sessions at MakeHaven, so that fellow advocates had a supportive space to unwind and create.

"I think it's how we dream," she said in an interview last month. "It's in the words that we share with each other, the dreams that we share. Organizing is very, very heavy, and what I've told myself coming out of that [work] is that I want to change the experience for other victim advocates."

Alyssa-Marie Cajigas Rivera Ortiz celebrating Marsha P. Johnson's birthday a week early in August. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

Across New Haven, that shifting conversation took other forms, from Black and Brown Queer Camp and voguing as resistance to an artist-led effort to bring back City-Wide Open Studios (CWOS). After Artspace New Haven officially closed its doors at 50 Orange St. earlier this year, a group of Erector Square, MarlinWorks, and Westville-based artists came forward to carry on a decades-long fall tradition that had once belonged to the organization.

As they worked toward the October festival—which for the first time in its history, actually brought in and compensated artists who live and work in Fair Haven—they created a grassroots, artist-to-artist model that ultimately flowed from individual studios into Erector Square's labyrinthine hallways and musical performances at Bregamos Community Theater.

“It feels great,” said artist Eric March at the time, shouting out fellow artists including Martha Lewis, Oi Fortin, Niko Scharer, Allison Hornak among others. “Putting together a bunch of people to do anything is hard, but this has been such a collective effort. Everybody has been so appreciative and positive. I think this year, people feel like they have skin in the game.”

That sense—of having skin in the game—has helped get artists through the remainder of the year, and reminded community members of the power of a good call-in, rally, and gathering in the process. Last month, dozens of New Haven Public Schools students channeled the same energy as they marched against book bans, which have reached an all-time high in the past two years.

So did members of Black Lives Matter New Haven and the Semilla Collective, using artmaking at two separate festivals in November to remind people of the necessity of joy—conjuring it, protecting it, spreading it more thickly than the grief trying to break through—in resisting state-sanctioned violence, from anti-Black police brutality to immigrant families separated at the Southern border of the United States.

Thabisa Rich leads "Ceasefire for Humanity," a musical showcase and discussion from the Rich Arts Collective at Havenly earlier this month.

“You being here and able to take up space is what we wanted and needed,” said Liberation U’s Ala Ochumare-Harris, a co-founder of Black Lives Matter New Haven with the artist Sun Queen, at a collaboration honoring Breonna Taylor last month. “We are here in our liberation, centering our joy, centering our ability to live. This is also organizing—art can create and shift movements.”

Even as the year began to wind down this month, it flowed through musicians' pained call for a ceasefire at Havenly, where members of the Rich Arts Collective had gathered to mourn the lives lost in the Israel-Hamas War. And it showed up as musicians in the New Haven Symphony Orchestra continued negotiations with NHSO leadership, in what is going on a year and a half without a contract.

At every turn, artists seemed to be working to articulate something Williams had herself pointed to in August, after the inaugural Artists State of the Union.

"My wildest dreams look like artists being healthy, living in a healthy community where they have the ability to make their art whenever they should want to, whenever they feel inspired to," she said. "Where they can just be an artist, because they're an artist."

"What is our process for holding these institutions accountable for not perpetuating this harm [going forward]?" she added, asking the question aloud. "And that's going to happen at the speed of trust. We're moving in a way that honors our bodies, our capacity, and gives us enough time and space to think about things strategically."