Culture & Community | Downtown | Arts & Culture | New Haven Free Public Library | The Hill

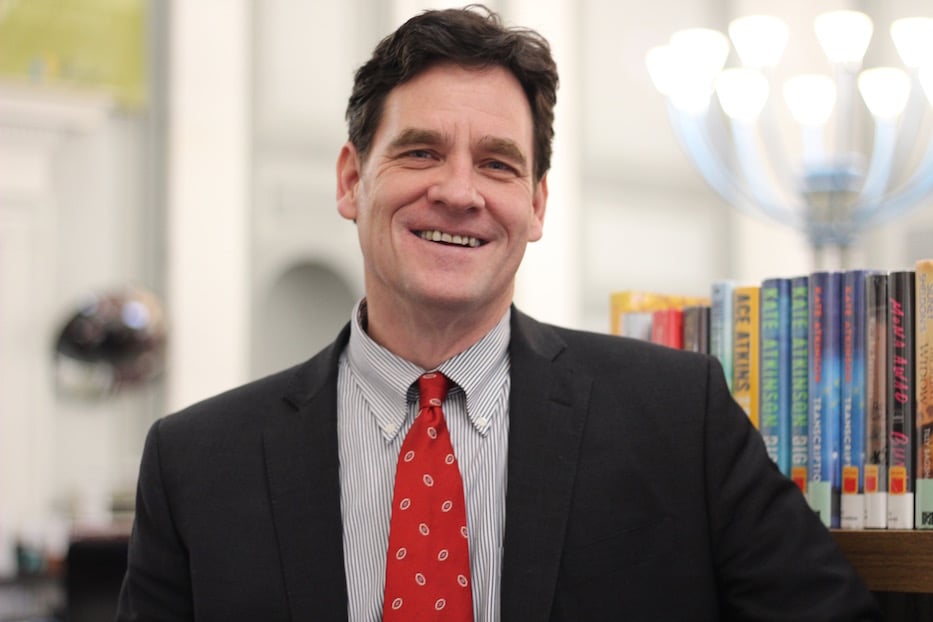

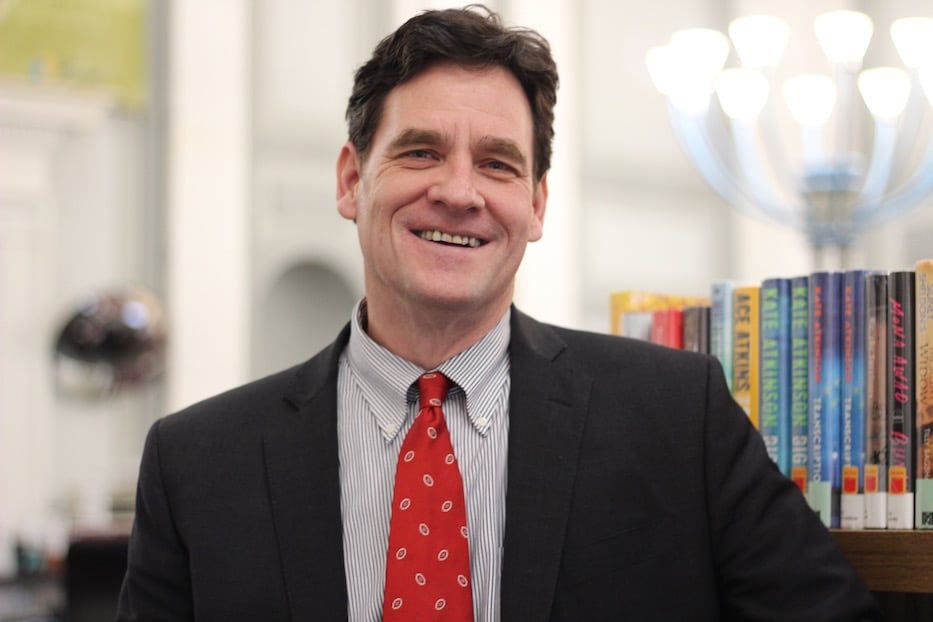

Jessen on Dec. 23 2019, when he was named City Librarian. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

John Jessen loved ideas. He loved laughter. Most of all, he loved people—and made sure they felt welcome just as they were, whoever they were.

In libraries, he saw community centers, employment offices and vaccine sites. In city budgets, he saw moral documents that could change a city's future one public service at a time. In a sprawling backyard, he saw space for a pond that was deep enough for laughter-laced cannonballs and summer swims.

At the end of his life, time was the only thing that got in his way.

Jessen, who rose through the ranks of the New Haven Free Public Library to serve as city librarian, passed away early Friday morning at home with his younger brother Nick and his wife Erika at his side. His siblings have since come to New Haven, where they have filled the Jessen home with stories about growing up together. The final week of his life was spent surrounded by his siblings, wife, sons William and Jack, and a community of friends and colleagues who ensured he was never alone. He was 56.

The cause was metastatic cholangiocarcinoma, a cancer that attacks the body’s bile ducts. He worked until last Sunday, when he went into hospice.

In the 18 years that he worked at the library, Jessen helped empower a generation of librarians. His dedication to public service was matched only by a sharp, lightning-fast wit and sense that he could always be doing more for the city he called home. One of his final acts was ensuring a $140,000 increase to the library budget, which will open all five branches of the NHFPL to the public on Sundays. In an interview in March, he called it “a game changer.”

"He was all about making everybody feel welcome," said his wife, Erika Jessen, as she looked out over their backyard Friday, where cherry and peach saplings spread their young arms toward the sun. “He knew that we were all just the same, and he wanted to know: ‘What’s your permutation of goals and struggles and things that you feel passionate about?’ He would just know we all had those same components in different permutations.”

“He never said no and he never judged,” said Stetson Branch Manager Diane Brown, who came through the library system with Jessen at her side and considered him cut from the same community-oriented cloth. “He was just a good person. If John was here right now, he would say, ‘Be a little more caring. Give a little more. Get up from behind the four walls of the library and get out into the community.’”

From Strawberry Point To The Elm City

City Librarian John Jessen, Stetson Branch Manager Diane Brown, Artspace New Haven Director Lisa Dent, and City Cultural Affairs Director Adriane Jefferson at the old Stetson Branch Library in September 2020.

The generosity and grit with which Jessen lived his life was born five decades ago in small-town Strawberry Point, Iowa, where the Jessen family has lived since the 1830s. A devout Catholic and the second eldest in a family of seven kids, Jessen grew up helping his dad, Terry, and grandfather, Jack, in the family's grocery store. When he was little, his sister Suzy Hamlett recalled, he would stand on a milk crate to reach the meat counter. By the time he was 16, he opened and ran the store on days that his dad had somewhere else to be.

It instilled in him a deep work ethic, said his younger brother Nick. Each year, Jessen and his siblings helped with “Strawberry Days,” during which the store served free strawberries and ice cream to the entire town. In addition, he grew up hearing stories about how on the store's 25th anniversary, his grandfather Jack had served slices of a cake that was large enough to feed over 1,300 people. Years later, Erika joked, projects of that scale helped him envision the pond, chicken coops, and fruit trees that appeared one by one in their backyard.

He was always a bibliophile, Hamlett said—but he also excelled in drama, speech, theater, band, and on the football field, where he played two undefeated seasons for the town in the early 1980s. He had a soft spot for painting that followed him to New Haven, where his bright, abstract canvases now hang in the hallways of his family's Westville home. He adored his siblings, sometimes talking with them into the wee hours of the morning.

Hamlett, who remained in Iowa with her husband, remembered one such pep talk that made it possible to face junior high after a particularly bad day. Jessen stayed up with her until 2 a.m., reassuring her that it was okay to go back.

“He just was always really good about stuff like that,” she said in a phone call Saturday night, while preparing for a flight to New Haven. “It really made an impression on me. He was always kind. He was such a good human. He was what everybody strives to be.”

Jessen also loved a good joke, honing a lifelong sense of humor that was frequently on display at the library. He led lip synching contests for his family, slowing albums down and then speeding them up as his parents and siblings tried to keep pace. He came up with nicknames for family members, a tradition he carried on when his nephews were well into their 30s.

Each summer, "we attempted to dig to China," Hamlett recalled. Jessen, with a mischievous smile on his face, often led the effort. Years later, when he returned to Strawberry Point for a few months, he brought nightly laughter into their home. She remembered an evening when she couldn't get the kids to calm down, because Uncle John was under the bed.

Jessen took Strawberry Point with him wherever he went. From high school, he studied political science at St. John's University in Minnesota, and then made his way to Brooklyn with stops in North Carolina and Iowa. In New York, he worked in publishing, founding a small Catholic press in the 1990s. He later managed the Community Bookstore, a Park Slope storefront with a cheery green awning and snugly packed shelves on 7th Avenue.

It was there, working among the shelves and a postage stamp of a back patio, that he met his wife Erika in the early 2000s. The two talked for two hours, letting a late winter snow fall around them as they chatted. By the time she moved to New Haven for her residency in 2002, she and Jessen were dating.

"I just remember thinking to myself, 'Oh, if I ever get married, I would love to marry a person like that,'" she said Friday with a laugh. Beside her, hundreds of books peeked out from shelves that line the living room.

Within a year, the two were living together in New Haven. Without a job, Jessen started Bookrounds, an online book club that grew to over 2,000 members within months. The format was simple: Jessen picked four or five books at a time, posted about them online, and met with small groups of members at local coffee shops, bookstores, and bars to discuss them. He held Christmas parties at the now-shuttered Anna Liffey's and used his connections in publishing to launch a series of author talks.

Harry Cohen, then working as an assistant manager at the Barnes & Noble in North Haven, remembered the curiosity and verve with which Jessen approached every book discussion. When Cohen took a job at the Yale University bookstore several years ago, he and Jessen planned events for the NHFPL. Their final collaboration was a book signing with George Takei in February 2020, just a month before the pandemic hit New Haven.

“John raised the bar for every person he came in touch with,” he said. “He was so interested in anything anyone ever had to say.”

He never turned that off when he left the library, Cohen added. He recalled eating dinner at the Jessens’ home in Westville last summer, and watching as Jessen entertained kids from the neighborhood. There was something in his gentle, open humor that drew them to him. “It was like he was the pied piper,” Cohen said.

When the author A.S. Byatt came to town for a Bookrounds event in 2004, Jessen booked the main branch of the library. City Librarian James Welbourne, who also sent a generation of librarians to school, was drawn to this young, doe-eyed book nerd from flyover country who loved public programming. As Brown tells it, he offered Jessen a part-time job on the spot.

For Jessen, who later said that he fantasized about “selling’ books for free,” it was a dream job. In the next 18 years, he transformed it into a home and a haven for tens of thousands of people.

“He was probably New Haven’s most unsung improv artist and creator of life,” said curator Frank Mitchell, who met Jessen in those years at a then-nascent community book bank in the Chapel Street Mall, and remained close with him for almost 20 years. “He really did show up and say ‘yes and’ to everything. He showed up and said ‘Yep, this will work. We can get the artists, we can get the writers.’ It was great to witness that.”

“He Was Genuine”

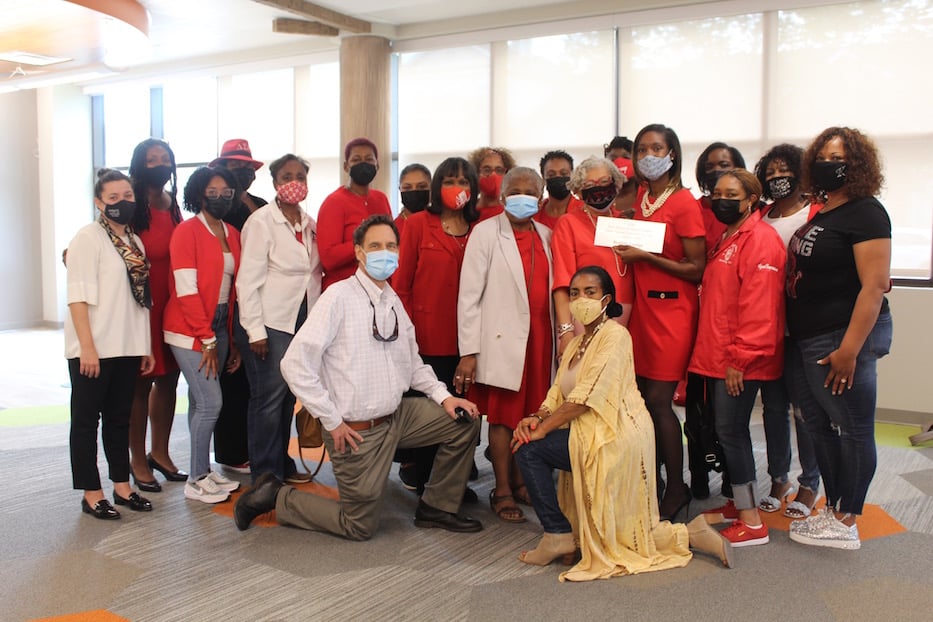

Jessen and Stetson Branch Manager Diane Brown earlier this year, on a tour for members of the New Haven Alumnae Chapter of the Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

From a part-time library assistant, Jessen grew his footprint in the NHFPL’s system, weaving a thick, durable web of community across many of the city’s 18.7 square miles. In 2006, he began his graduate work in library science at Southern Connecticut State University (SCSU), earning his MLIS degree in 2008. By then, he was already working as an outreach specialist for the NHFPL, a role in which he juggled and expanded community partnerships. Brown, under whom he served briefly as a children’s librarian at Stetson, became his guide to the city.

“We would go out, and he was very well liked and received because he was genuine,” Brown said in a phone call Saturday. “We shared programming ideas with one another. We talked about moving up in the system. Mr. Welbourne used to say, ‘I can teach you how to be a librarian but I can’t teach you how to be a humanitarian. I can’t teach people that.’ John was a humanitarian.”

In 2012, Jessen was named branch manager at Wilson Library, a red-and-brown brick building that rises from Howard Avenue in the city’s Hill neighborhood. At the time, the branch library was running on a staff of just two people, which meant Jessen was constantly in motion. Rarely behind his desk, he worked to assess the neighborhood’s needs, from tech literacy and Spanish-language materials to his “Reading for Rabbits” series.

Taking a page from his own childhood, he often brought Jack and William into work with him, setting up a makeshift “office” for William in the library’s conference room. William, now 13, still refers to those years as “the good old days.”

Karina Gonzalez, now a public service administrator at the NHFPL, praised Jessen for an approach that put the community first—whether or not it meant playing by the rules. The first time she walked into the library, she remembered Jessen jogging down the stairs, and mumbling something to her about her interview. She realized quickly that he was peeved—not because she was there, but because he was away from the public desk.

When she was hired as a library technical assistant in 2015, Gonzalez became part of what she called Wilson’s “joyful chaos.”On her first day on the job, Jessen was midway through an NHFPL checklist when he discarded it and began speaking to her candidly. She was floored, and then delighted.

“Pretty much, the only thing I can say to you is we’re here to help patrons,” she remembered him saying. “The only thing that matters is that you feel that you’re doing the right thing for everybody.”

“John would have a personal history for everyone who walked in,” she said. “He knew their history. He knew their family. He was constantly moving all the time without regard for the limits of human energy. I was like, this guy is insane. He clearly knew who everyone was, and he clearly knew everything about books. I was so impressed and a little scared.”

Jessen saw the library’s rules as porous, she added. He didn’t get mad at patrons when they forgot their overdue DVDs, because he understood that they might not have the bus fare to double back and retrieve them. He was fine with parents who wanted to check out extra books and movies for a long weekend. True to his roots as a children’s librarian, he focused on bringing families into Wilson, and giving them programming that made them excited to stay.

Once, Gonzalez remembered watching one family come into the building, and learning from Jessen that their daughter needed tutoring. It wasn’t in her job description—but it was what the moment called for.

Within weeks, she was part of the girl’s educational life, attending parent-teacher conferences to translate for her mom. Another time, a patron came in looking for job skills, and became agitated when Gonalez tried to help her. When Gonzalez walked away, Jessen let her take a beat—and then encouraged her to head back and help her. "This is not about you," she remembered him saying.

“He did not care who you were,” she said. “He did not care if you had a history of coming in and being rude or combative, every day was a chance to reset it.”

NHFPL Photocollage.

Kristin Mancini, who now manages the cataloging department, also looked to Jessen as someone who made things possible, no matter how hard they initially seemed. During his tenure at Wilson, she watched him use every square inch of the library for community meetings, birthday parties, summer camps and literacy groups. It was a tradition that Luis Chavez-Brumell carried on when he was named branch manager in 2018.

"He would use a closet if he had to," Mancini said Friday, sitting in the Jessens’ backyard. "He was so generous with his time. He was like, open door, you can talk to him about anything. He treated everybody the same. With utmost respect, caring for everybody as human beings."

It wasn’t only people within the library that saw that. Former New Haven Police Chief Otoniel Reyes, whose kids attended St. Thomas's Day School with Jessen’s sons, was a lieutenant serving as Hill South District Manager at the time. He remembered how quickly Jessen made himself a part of the Hill community, learning the neighborhood like it was his own (for him, it was). He made it his business to know every person who stepped into the library.

“John was just a very loving guy, and a genuine soul,” Reyes said Friday at the Jessens' home. He marveled at how Jessen, serious when he needed to be “loved to laugh” and always had a good joke ready.

Jessen continued to ascend, following a path Welbourne had set him on over a decade before. In 2017, he was named deputy director of the library, serving under City Librarian Martha Brogan until she retired in 2019. Under Brogan’s leadership, the library expanded its footprint as a free and open resource, becoming a service hub and warming and cooling center amidst increased housing insecurity in the city. In 2019, he was part of the team that snagged the National Medal for Museum and Library Service, the nation’s highest honor in the field.

His first year on the job, Jessen began subscribing to a weekly newsletter from author Ryan Dowd that included tips on working with homeless patrons to give them the access and dignity to which they are entitled. Each week, he sent the tips around to staff, building a resource base and teaching tool. Behind the scenes, he applied for funding that would allow the library to grow its social services—a goal that he later realized when the NHFPL brought on a social worker earlier this year. In some ways, that work was second nature, because he'd been doing it for years already.

"He taught me how to be kind to the patrons," said Mitchell Library Branch Manager Marian Huggins, who joined Wilson as outreach librarian in 2015, and grew the library's programming to include the Urban Life Experience book discussion series, film screenings and author and scholar talks. "He recognized the humanity in everyone. For him, it was building relationships, not just conducting transactions."

Jessen was named city librarian on Dec. 23 of 2019, one of the last decisions Mayor Toni Harp made in office. He received his cancer diagnosis a week later, on the cusp of a new year. Friday, Erika recalled the number of times that he would finish a chemotherapy session and drive straight to work, staying late to make up for the hours he had ostensibly missed. He remained extremely private about his diagnosis until last week.

"He said, 'You know what? I'm gonna be fine,’” she said. “And he was. The crazy thing is that he held that promise. He didn't miss a day of that contract."

When Covid-19 hit New Haven in March 2020, Jessen was one of the first city officials to make the online pivot. In addition to virtual resources, he worked to spread the word about social services, from the emergency hotline 211 to Liberty Community Services’ website. He worried constantly—including in interviews with the Arts Paper that first week of the pandemic—about the patrons who relied on the library’s computer lab, onsite job and tax assistance, and daily shelter. Even as he navigated curbside pickup, he worked with staff to reopen the computer center as soon as it was safe to do so.

In the midst of a pandemic, he increased accessibility. With staff and board behind him, the library eliminated fines and used relief funding for WiFi Hotspots and Chromebooks that patrons could check out. He launched vaccine and booster clinics that leaned on librarians as trusted messengers. He and his staff made space for the community to grieve the toll of Covid-19. With Brown, he reopened the new Stetson Branch Library, now the anchor of the Dixwell Avenue Community Q House.

His legacy was one of lifting up not just the library, but its people. During his tenure, Jessen oversaw a number of promotions, including Chavez-Brumell from Wilson branch manager to deputy director, Marian Huggins from Wilson outreach librarian to Mitchell Branch Manager, Meghan Currey to Wilson Branch Manager, and Gonzalez from library technical assistant to public services administrator. Working with Brown, he encouraged New Havener Shayla Foreman to pursue a library technical exam, and hired her at Stetson when she did.

“John climbed the ladder, but his way of being was on the ground,” said NHFPL Board President Lauren Anderson. “He was working alongside everyone. I think some people who ‘rise up’ through the system forget that. John was just, in his mind, he was working side by side with every single person in the library.”

Sunday, Gonzalez said that he long dreamed of establishing a grad school fund specifically for internal library staffers of color. Even in state, Masters of Library and Information Science (MLIS) programs are expensive—and in turn, still disproportionately white. When Jessen looked around and saw a library that did not reflect the city it served, “it was appalling to him that no one did enough about this,” she said.

Even as he transformed the library, Jessen rarely saw the change he was making. He was quick to credit colleagues with the work, then point to how much there still was to accomplish. In interviews with the Arts Paper, he often spoke with a self-deprecating humor, bemoaning a lack of polish that was never actually apparent.

"John never came home and said, 'This is what I accomplished,'" Erika said. "He came home, and said, 'This is what I can't get done. This is what is in my way. This is what I need to do. This is what I need to push through.'"

“Dignity, Humanity, and Love”

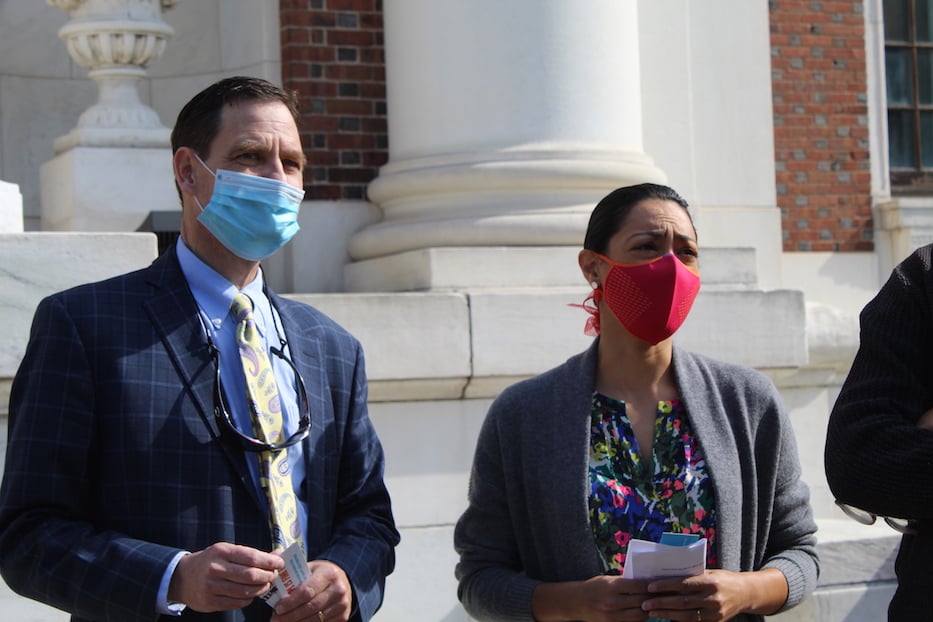

John Jessen with Shana Schneider, then president of the NHFPL Board, in September 2020.

Jessen’s role as a mentor in the community extended far beyond the library. Outside of work, he was a doting dad, husband, friend, and brother who never forgot where he came from. He loved to work in the backyard, where a pond now stretches across one half of the space, and fruit trees and flowers spring up on the other. He did service and volunteer work with LEAP (Leadership, Athletics, & Education in Partnership), New Haven Reads, and Common Ground. It seemed that he rarely stopped moving.

Kate Cooney and Lizzy Donius, both close friends of the family, remembered a key planning session that Cooney convened years ago, during which Jessen and Donius walked her step by step through neighborhood engagement in New Haven. Cooney, who leads the Inclusive Economic Development Lab at Yale, had set up a session for New Haveners in a Yale classroom. Jessen explained that she was doing it entirely the wrong way. She had to come to the community, starting with the city's Community Management Teams.

“John introduced me to a few key people in Hill South and suggested that I hold the information session at the Wilson library instead,” said Cooney, “I’ve followed that formula ever since.” For the librarian, that kind of advice was about how to lead a life.

“John's death hits so hard because he was so alive as a person, husband, father, neighbor, citizen, and community leader,” wrote Michael Morand, president of the NHFPL Foundation Board of Directors and public relations and communications director at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, in an email Saturday. “He helped this great place and its residents live more fully and freely. In a world corrupted by narcissism and noise, John catalyzed connections to create a more beloved community.”

That community was on display during “the most magical week” of goodbyes, Erika said Friday. When Jessen went into hospice last week, dozens of friends gathered at their Westville home, representing every chapter of Jessen’s still-young life. A group of kids from the neighborhood rallied around Jack and William, going for night swims, bonfires, and late-night walks.

Donius, who leads the Westville Village Renaissance Alliance, became a fixture in the house, where she was still firmly planted Friday. On Thursday night, musicians Chrissy Gardner and Tim Kane brought over their instruments, and sang to Jessen during the final hours of his life.

Mayor Justin Elicker, who visited last week, remembered entering the home and feeling particularly moved by the multigenerational community he found there, ready to lift the Jessen family up in any way they could. In a phone call Monday night, he called "a true reflection and a celebration of his life."

"The New Haven Public Libraries feel like home to everyone, no matter who they are, and John I think was very representative of that spirit and contributed to it," he said.

Jessen leaves a legacy of community. Last Friday, memories rose to the rafters and slipped into nooks and crannies. In one, Jessen had a prank up his sleeve that left the whole room in stitches. In another, he was picking up trash with his sons Jack and William outside of Wilson, leaving passers-by flummoxed as he beautified the space. The recollections floated from the kitchen to the living room, the backyard to the front porch. They are how friends and family will keep Jessen's memory alive for years to come.

“John led the library with dignity, humanity, and love,” wrote Morand. “His love for family, library, and community is a light that cannot be extinguished: his legacy shines like a beacon to guide us through these tough times. So many of us are going to miss him enormously -- and going to remember him fondly and fiercely. New Haven is so much the better because John Jessen lived and led here.”

A visitation will be held Tuesday, May 31, from 5 to 8 p.m. at Howard K. Hill Funeral Home. A funeral mass is scheduled for Wednesday, June 1, at 10 a.m. at St. Mary Church, 5 Hillhouse Ave. Those wishing to donate to the library in Jessen’s honor, which will go toward the beautification of outdoor spaces at all five branch locations, can do so here. Please specify that the gift is in honor of John Jessen.